Exploring the History of Whales and Whaling

A number of our graduates go on to pursue careers in the GLAM sector – that is, Galleries, Libraries, Archives & Museums. Charlotte Colding Smith completed a PhD in History in 2010, and has gone on to work at a number of institutions and museums internationally. She is a Senior Expert Fellow at the German Maritime Museum, Bremerhaven, where her research explores whales, whaling and related objects in the museum’s collection. Charlotte spoke with MA Candidate Jen McFarland about her approaches to visual and material culture in her research, and the challenges and rewards of working in the museum sector.

Could you tell us a little about your current role?

Up until the middle of this year my role was as a Research Fellow at the German Maritime Museum (Deutsches Schifffhartsmuseum – DSM), Bremerhaven, which is one of eight Leibnitz research museums in Germany. These strive to present research in an exhibition format, as well as researching and publishing on the items in the collections themselves. Since July, I have continued to work in conjunction with the German Maritime Museum as a Senior Expert Fellow.

My main task has been in helping to develop the whaling section of the new permanent exhibition, with the main themes focusing on shipping and the environment. My emphasis has been on whaling in the twentieth century, in relation to whaling and overwhaling as the use and overuse of resources.

Further to this, I am helping develop several projects relating to the historical collections of the German Maritime Museum, including scrimshaw (carved whale ivories), industrial whaling products, whaling log books and photographs and diaries.

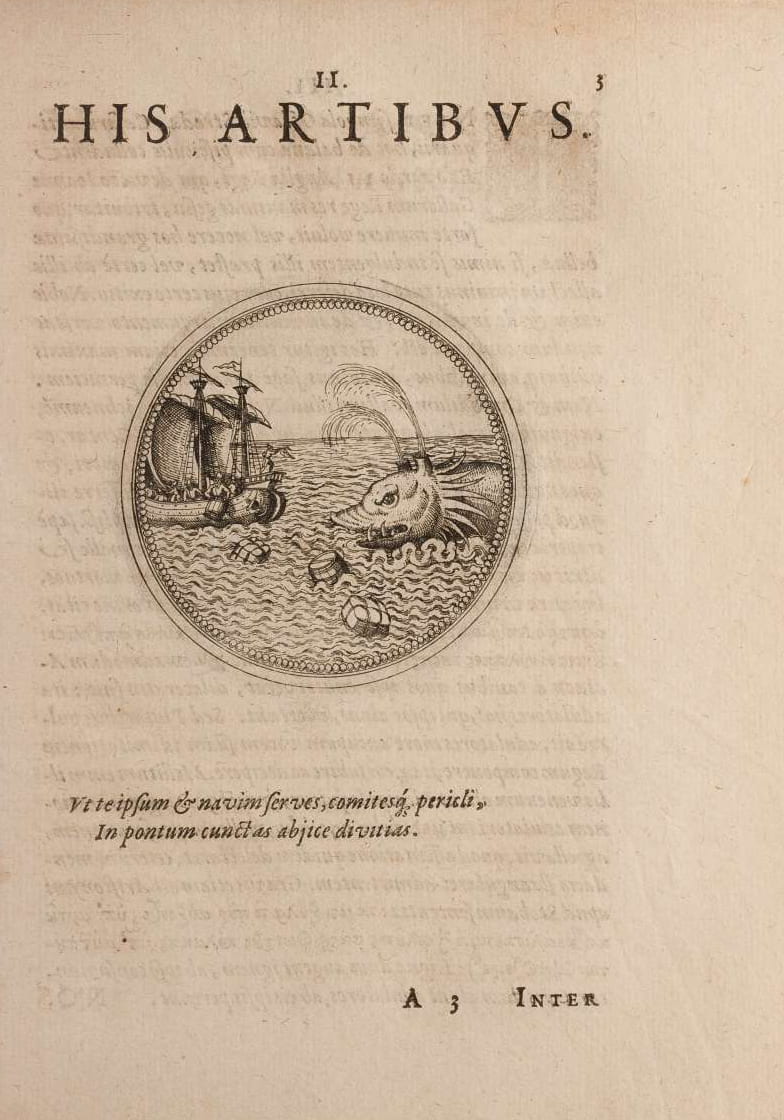

I am also carrying out research linked to exploring the whale in sixteenth- to eighteenth-century collections, scientific research and prints and drawings, especially to the collection and perceptions of whales in early modern museums. Objects include whale skeletons, teeth and prepared whale skins. I am researching not only the objects themselves, but also the inventories of the collections in which they appear, the scientific publications on the whales (including Ole Worm’s controversial publication stating that so-called ‘unicorn horns’ were in fact narwhal horns) together with the letters between collectors and scholars interested in whale bones and other maritime objects.

I am also looking forward to be able to expand this research in many ways, including a Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Herzog August Biblitothek in 2021, where I will investigate how whales were presented in prints and book illustrations in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, during the Greenland Whaling Boom, in which the offshore whaling industry from Continental Europe developed, whale oil boomed in price and the curiosity surrounding the creatures grew.

And what drew you to whales and whaling history?

The whaling collections is one of the strengths of the German Maritime Museum. When I began my work there (originally on an International Fellowship and subsequently as part of the research team) I was asked if I could work with the whaling collection. Subsequently, I was delighted to find that it fitted in with several of my previous research areas, including sixteenth- to eighteenth-century history relating to travel, trade networks, and collecting. In addition, many Early Modern printed images and drawings of whales focus on the fear and fascination of giant monsters and the omens and portents related to whale strandings and whale capture.

The curiosity and fascination of the Early Modern German Speaking World with the Ottoman Empire comes from the perspective of fear of military power, and the Islamic religion, as well as the fascination with an unknown culture, language and costume from distant lands. Many of the descriptions and perceptions of whale capture and strandings come from a similar mindset (especially when written by the same authors or illustrated by the same artists). Images of the whale also permeate popular to scholarly texts ranging from broadsheets, biblical texts and church decoration (especially linking to the story of Jonah and the whale) to scientific and collections treatises.

The Early Modern perceptions of the whale within this framework are definitely what drew me into the topic. However, the stories that can be told when moving through history for several centuries have also gripped me. These include, for instance, the objects created during the nineteenth century Yankee whaling boom (the time of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick), to diaries and log-books from the factory ships of the early to mid-twentieth century relating to whale oil (mostly for margarine production), whale meat and bone meal.

I have also become fascinated by the debates leading to the banning of whaling. These originally related to questions of the sustainability of whale stocks linked to increases in technology and over-whaling and moved to the focus of the beauty of whales and the cruelty of the practices within whaling. It is a privilege to be able to explore these stories within both the public outreach of curating the museum and interviews in which I have taken part (one of which will appear on German television later this year, and the other is already available on YouTube [watch/read below]). This is in addition to seminars, conference papers, journal articles and other more traditional academic output.

Can you tell us a bit about print and material culture in your research, and how the positions you have held might have changed/expanded your approach?

During my BA and PhD, I very much leaned toward printed images and book illustrations as historical sources (my majors as an undergraduate were History and Art History, with a lot of German courses as well). I also had many casual jobs – working in libraries and as a research assistant working with image permissions, as well as several fellowships in major research libraries and print collections where I exclusively worked with 2D images, mostly prints and with some drawings and watercolours.

At the German Maritime Museum I have had the opportunity and challenge to work with 3D material, though the collection also contains several prints, drawings, paintings, photographs, newspaper reports, journal, log books, together with historical film material relating to whales and whaling. I have also had the chance to tell stories using digital technology, including virtual and augmented reality, which has been a lot of fun and is an area in which I would like to work more in the future.

3D objects and material obviously pose their own challenges and questions in terms of presentation and conservation. This is especially true for the material of the whaling collection, including harpoons, harpoon cannons, sloops and a 1930s whale-chasing ship, all of which have suffered weather and saltwater damage. It is also true of other materials including those made from whale bone ivory, which is sensitive to light and heat. Creating an exhibition using these objects and working out how they should be best used in order to tell the story of the environmental impact of whaling in conjunction with the individual narratives of German whalers from the 1930s and 1950s, has also moved me far beyond the process of writing an article or a book chapter. Explaining these ideas to a broader public than the readers of a scholarly work, has at times turned my ideas completely on their head, but is an amazing amount of fun!

My own approaches seem to be evolving every day. The chance to work with 3D material, film photo archives and virtual material has been a revelation as well as a challenge. Having a chance to interact directly with the design team within the planning process of the new exhibition is also amazing as it considers visual space in new ways leading to alternative utilisations. The new exhibition will be semi-permanent, but individual displays will be changing, so the vitrines [display cases] and building material will need to be adjusted and moved in order to best showcase the material. The special dimensions of the room have also been a challenge, due to concerns of lighting, high ceilings and open spaces. These questions are still in discussion with my colleagues and the design team and I am really looking forward to seeing the results.

Do you have a favourite (or especially inspiring) image/object that is part of your research, and why is that?

I love images and objects that tell specific stories and it has been a lot of fun researching them all and I look forward to presenting them in new contexts. In addition to this there are so many whaling objects in such a variety of media from the whaling ships themselves and the tools used for catching and preparing the whales to ship models and moving on to paintings, prints and carved representations. Each one is fascinating in the story that it can tell.

That said, one object in which that I have completely fallen in love is a sixteenth-century whale ivory, which might have been a decoration on a staff or ceremonial chair, this is covered with tiny figures, possibly representing a fraternity (DSM Inventar-Nr.: I/8741/99). We are hoping to explore this item more fully, through a CAT scan and DNA analysis and I am also hoping to find archival and textual evidence of similar objects and how they were used in the ritual the cultural life of courts and of patrician elites.

As a historian, what do you like most about working on projects with public output? And what do you find the biggest challenge?

I have wanted to work in museums and exhibitions since I was about ten years old and I discovered that this was a possible career. My time at the University of Melbourne only increased my awareness of the ways that historians can contribute to public outreach and the skills that a history degree could contribute to this, whether at universities, in archives, database work, websites, or museums and exhibitions. It is a dream come true to work in this environment and to be part of the process of telling these stories.

I would say that the biggest challenge is knowing your audience. The German Maritime Museum has both a scholarly and academic output in terms of papers written, conferences and workshops held in addition to university courses taught at the Universities of Oldenburg and Bremen. However, the local public of Bremerhaven have a different set of questions or interests compounded from expectations and history. Bremerhaven traditionally had many jobs in the shipping industry and fish factories, as well as being the major port for the American Zone in Germany from 1945 till the early 1990s, all of which led to different expectations relating to the place of the museum and the stories that it should present. More recently, discussions with the refugee community in Bremerhaven, together with questions surrounding climate change and Fridays for Future, have also taken a prominent aspect of the narrative the museum wants to present taking exhibitions and discussions in completely new directions.

The other challenge is being able to present the material in a short text for a label. After so much research and information, presenting an object in 80 words is almost impossible. Luckily there are also chances to expand on the texts and topics in presentations, conference papers, book chapters and articles and of course catalogues!

Do you have a favourite memory of Melbourne Uni?

There are so many wonderful memories that it is hard to think of just one. Going back to my BA, it was at Melbourne University that I was able to find out who I was and find friends who shared my interests and passions. All the wonderful conversations that often went late into the night over drinks at a pub or over cake at Brunetti’s are definitely important to who I am today. Some of my best friends are ones that I made during my first semester at University and I am in touch with many people from both my BA and PhD that I love meeting up with when I am in Melbourne. I have also managed to catch up with some in cities including Berlin, Nuremberg, Vienna, New York, Boston, London, Oxford and most recently Cambridge, which is always a treat.

In terms of course work, I loved being able to explore primary textual and visual sources and their stories in lectures and tutorials, though at times I felt frustrated that I could only dip my toes in the surface of the research and archives. Honours year meant that I began to be able to explore this process more fully, but it was really as a postgraduate, and in the time after the PhD that I have been able to explore these questions deeply enough to begin to be satisfied. My PhD was also the time that I learned about what it took to be a researcher and how these skills could be transferred to the wider world. In many ways this was also the time in which I grew up as a person and an academic, which could be challenging but was ultimately incredibly rewarding.

Of course, my Melbourne Uni supervisor Charles Zika should be specially thanked, as it was he who opened my eyes to how images contribute to historical research – which has become the centre of my own approach. I was lucky enough to do a course with Charles during my first semester of university, which, together with guest professors (some of whom I have been lucky enough to work with in Germany), set up many of the ideas with which I have later worked, including collections history and the history of the book.

What advice would you give to incoming postgrads?

My main bit of advice is to love the topic that you are researching. At the end of the day, and towards the end of the PhD, there are times when you are trying to format the footnotes or get the right word count and sentence structure where you will hate the process and even the PhD itself. However, if you start from a place of love and curiosity about the topic, it will make it worthwhile, especially when a question is resolved and you can tell a story differently or more completely than previous scholars.

I would also say that it is important to get experience of history outside the PhD itself, whether this is from teaching, exhibitions work, cataloguing, database entry or other types of research assistant work. The skillset that you gain from the PhD has so many ways of transferring, but while you are in the middle of it (or for me personally, just after I had handed in my PhD) it can sometimes be hard to see what these are.

Lastly, I would say it is important to talk to other PhD students and researchers. These are people who share your passion and will sympathise with many of the struggles you are facing. If you look to the students ahead of you, you might also get tips on the archives that are open to you and the types of work that you might carry out there. I would also say that looking to what your fellow students have done and are planning to do might give ideas of how to approach the world beyond the PhD.

In 2021 Charlotte Colding Smith will take up a postdoctoral fellowship at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, Germany, southeast of Hanover.