Scientist and Killer: A Split Life

How does an urbane chemist become a Nazi, then go back to being a respected researcher? And what does it say about the extent of the humanity in all of us? Dr Oleg Beyda explores the story of Hans Beutelspacher in this article, originally published in Pursuit.

In his diaries and letters, the World War II German General Gotthard Heinrici preserved horrific details of just how ferociously the war was waged in the Soviet Union.

And in these diaries we stumbled on a disturbing character – the translator at the general’s headquarters.

“Yesterday in Likhvin, and today not far from here”, wrote Heinrici, “Lieutenant Beutelspacher did away with a total of 12 partisans. I would never have thought that this inconspicuous little man would be so energetic. He is exacting vengeance for his father, his mother, and his brothers and sisters, whom communism has sent either to their graves or into exile. He is a pitiless avenger.”

Heinrici mentions this Lieutenant Beutelspacher several times as leading the effort against the Soviet partisans fighting the Germans from behind the lines.

The general’s notes have been translated into several languages and are repeatedly cited in historical literature, but historians have shown no interest in Heinrici’s seemingly insignificant translator/partisan hunter.

Intrigued, we went looking for him.

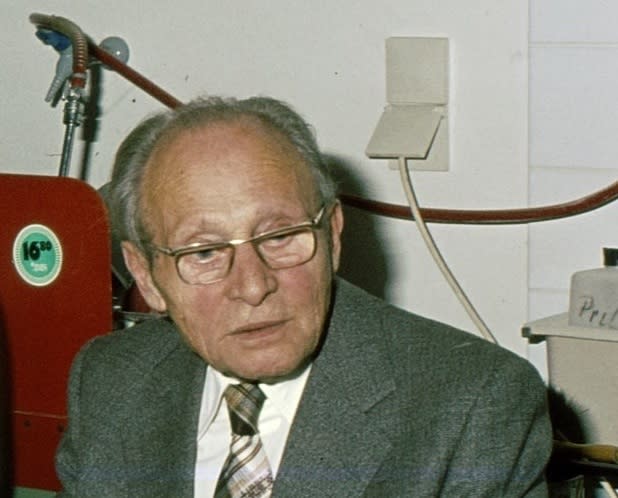

What we found after years of digging was an affable university lecturer and scientist well versed in Russian literature. A man who would survive the war and continue his successful career as if nothing had happened.

In a 1941 address register we found an entry for Beutelspacher – a Dr Hans Beutelspacher – and from there we hunted him down in various archives.

Russian was a second native language for Beutelspacher, who had been born in 1905 to the family of an engineer in the German colony of Rosenfeld, near Odessa in the then Russian Empire.

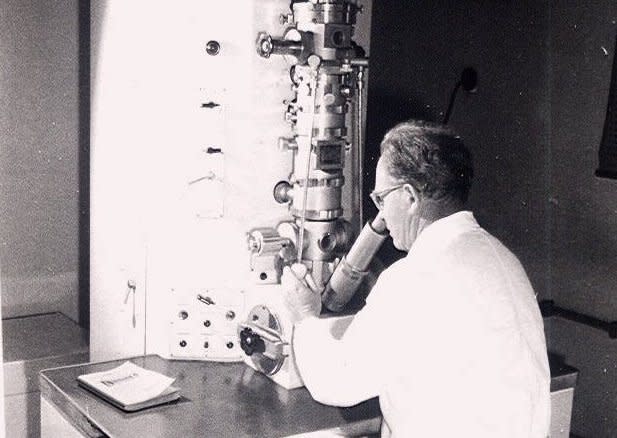

After finishing school, he studied chemistry from 1922 to 1926 before leaving Russia to complete his education at the Hochschule für Technik in Stuttgart.

In Germany, the chemist became a soil scientist, and from the summer of 1928 until 1933 he worked on his dissertation. Supervising his research was Margarete von Wrangell, the first woman to become a full professor at a German university.

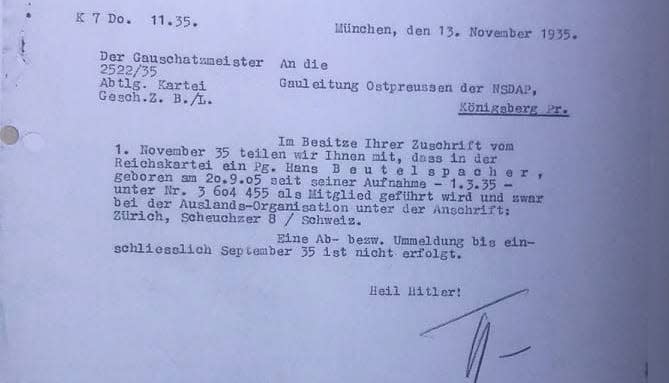

In the mid-1930s, the newly minted doctor moved from the German southwest to settle in Zürich, Switzerland. It was there, in March 1935, that Dr Beutelspacher joined the Nazi Party. His party number was No. 3 604 455.

It appears that initially the party was suspicious.

Wary of Communists, the Nazi Party’s Office of Foreign Affairs was keeping tabs on Russians of German ancestry, and preserved in the archives is a warning against collaborating with Beutelspacher – we don’t know why.

Dr Beutelspacher soon moved to Königsberg in eastern Germany where he was to work under the direction of Eilhard Alfred Mitscherlich, a famous agricultural scientist.

Beutespacher published actively and attended European scientific conferences.

The course of his scientific life was then interrupted by the war. In the autumn of 1939, Beutelspacher was called up to serve in a signals battalion stationed in Königsberg.

He had scarcely managed to get himself measured for his grey-green uniform when in late October he had to check into the sick-bay diagnosed with “gonorrhoea”.

By June 1941, he found himself serving in the intelligence section of the 43rd Army Corps, commanded by General Heinrici – part of the German forces that would invade the USSR later that month in Operation Barbarossa.

Beutelspacher made friends with the general, advising him to read Tolstoy and Leskov in order to understand Russia. In the intervals between battles Heinrici did, indeed, set about mastering Russian literature.

After initial victories, the invading Germans were soon plagued by attacks by partisans along their supply lines – a challenge they met with indiscriminate violence.

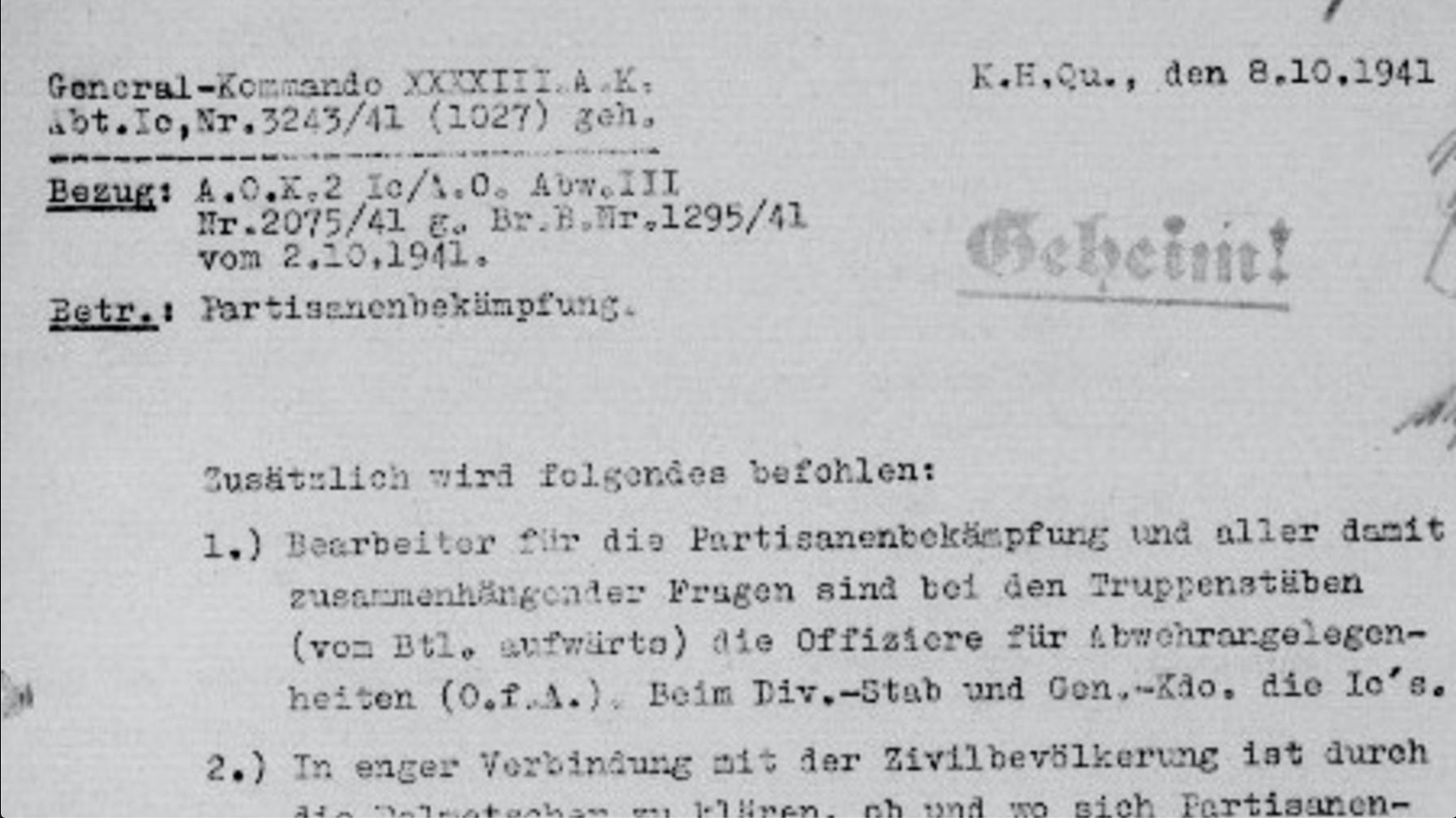

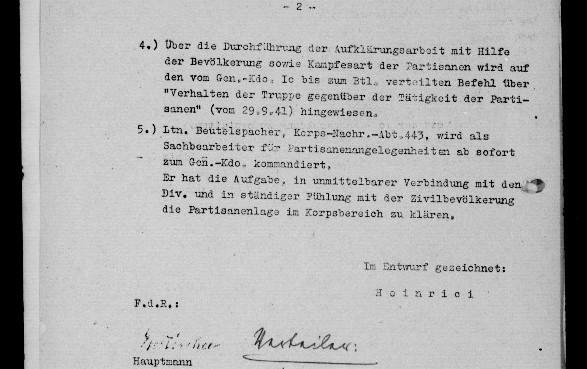

In October 1941, Heinrici’s corps began forming teams for anti-partisan warfare. The scientist, now with the rank of lieutenant, was swiftly transferred from the signals battalion to the Corp’s headquarters staff, with responsibility for partisan matters.

Prior to this, Beutelspacher had been expeditiously translating texts for his superiors. Now, displaying still greater efficiency, he began translating lives – to the other world.

“Our Russian translator has taken to the struggle against them with exceptional energy”, Heinrici wrote. “In the past three days the translator has managed to capture and finish off 15 of them, including several women. The partisans are fiercely loyal to one another. They let themselves be shot, but do not betray their comrades.”

In another note, Heinrici records that; “On the sixth alone Beutelspacher captured 60 people, including 40 Red Army troops. He managed to bring in twenty of them and finish them off. They hanged one young lad in the town, that is, Beutelspacher relieved the field police of this melancholy task and carried it out himself.”

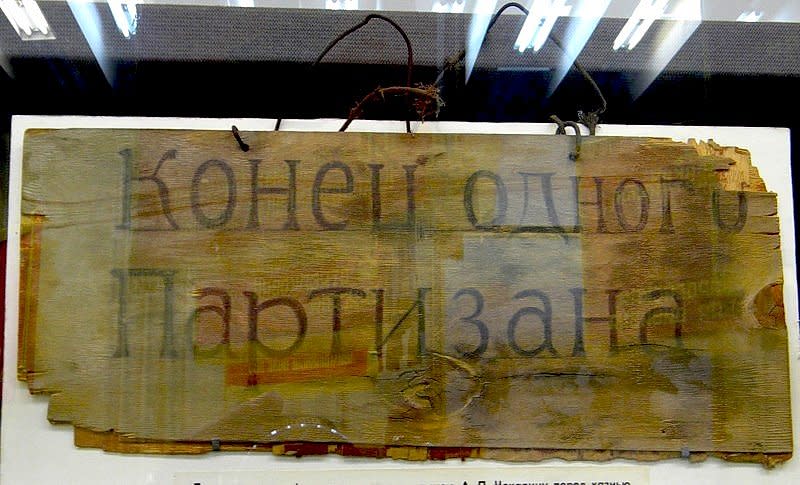

The young man he hanged was Aleksandr Chekalin. The sixteen-year-old had been an active member of the Soviet underground, and was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. In 1944, the town of Likhvin was renamed Chekalin.

For 70 years nothing was known about who had hanged Chekalin, with the act ascribed simply to anonymous ‘Germans’.

Beutelspacher’s zeal for the job sometimes got on Heinrici’s nerves.

“I told Beutelspacher not to hang partisans closer than a hundred metres from my window. Not the most pleasant sight in the morning.”

But mostly the general appreciated his work.

[Beutelspacher] is fighting these partisans with desperate energy, since the Bolsheviks killed his father, eliminated his brother and sent his mother and sister to Siberia to build roads. Again and again, accompanied by field police and by three Red Army soldiers who are loyal to him (they are the children of peasants), he heads out on a mission, and never returns without having shot or hanged a few bandits. But those people almost always meet their deaths with cold-blooded stoicism.

We don’t know for certain what Beutelspacher was doing from the year 1942. A registration card that certified his military pension in 1971 contains no information about his subsequent service, since the applicant didn’t report these details.

All that is shown is the date, 30 March 1945, when his service ended.

From his prisoner-of-war form, we know that at the time of his capture Beutelspacher was serving in the 172nd Reserve Division, the remnants of which surrendered to the British near the coast of the North Sea.

On 12 July, he was released and set off to meet with his wife, who had managed to be evacuated from East Prussia.

No-one appears to have learned of his war crimes. The year 1945 marked the onset of a Stunde Null (zero hour) for all of Germany. Beutelspacher too had his wartime life ‘annulled’, though thanks to Heinrici’s writings, not completely.

By the late 1940s, Dr Beutelspacher had finished up in Braunschweig, where he headed a department in the Institute of Soil Biochemistry (Institut für Biochemie des Bodens).

From 1950, he again published articles on soil science. Later, his interests shifted in the direction of electron microscopes and spectroscopy. For example, he became the co-author of a book entitled Atlas of Infrared Spectroscopy of Clay Minerals and their Admixtures.

We managed to speak with one of Beutelspacher’s former colleagues at the institute, who recalled him as an exacting director, but agreeable in his personal dealings, and a great joker. Sometimes, over a beer, he would recall his youth in Russia.

Mere hunting stories were related. “A war criminal? No, impossible! Such a nice little old man.”

His stories never touched upon the years when he was a hunter, an executioner and a predator – the corpses of victims frozen stiff, the dying convulsions of civilians hung on the slightest suspicion, the mud, the blood, the cruelty.

The USSR, too, showed no interest in searching for the murderer of Chekalin, the Hero of the Soviet Union. On the contrary, Soviet soil scientists gladly visited Braunschweig in Germany, where the urbane Beutelspacher was in high demand as a translator, guide and scientific consultant.

In 1958, he even translated into German a book by the Soviet Professor Mariia Kononova, Die Humusstoffe des Bodens.

In the late 1970s, Beutelspacher died peacefully, without having suffered any punishment, though we don’t know what the state of his conscience was.

Stories about Nazis often serve as a moral prop, a means of demarcating the past from the present. When modern readers contemplate the horrors of the Second World War (or of any war) they can reassure and fortifying themselves with their confidence in their own moral progressiveness.

It is, after all, easy to say, “Here’s the story of another monster. If I’d been in his position, I’d have behaved differently”.

Other people, more cynical, would perhaps explain his acts as having been motivated by revenge. But in post-war meetings with Soviet chemists, this “pitiless avenger” turned into a cordial colleague.

We shall never know whether Beutelspacher ever believed in Nazism, or whether he simply ran amok, encouraged by his impunity in the face of the killings that were so easy to carry out.

Today we like to consider ourselves wiser, better and more scrupulous than the people of the past. Our life-spans have increased, our knowledge of the world has expanded, and numerous gifts of civilisation smooth our personal dealings and brighten our leisure. But no such changes have occurred in our psyches.

This is one of the great lessons of history – the grandiose monument of our humanism is unstable and needs work because it may collapse at any moment.

Losing our humanism it seems has nothing to do with our level of education or intellect; even the most judicious people can become infected with ideas that turn them into obedient weapons of savagery and death.

If we are to believe the gloomy philosopher John Gray, the morality of each of us over the centuries has remained our personal illusion. Reality is the outcome of this chronic imperfection, as the recent publication of the Brereton Report into alleged war crimes in Afghanistan by members of Australia’s special forces should remind us.

When it comes to human behaviour, therefore, we can’t comfort ourselves by viewing a man like Beutelspacher as some kind of exception. The implication is that the bloody twentieth century hasn’t vanished into our past – it is merely lurking in the shadows.

It would be best if it were to remain there permanently, but there are no guarantees of this in any of the tablets, scrolls, and books that have come down to us from previous centuries.

Feature image: General Gotthard Heinrici’s 1941 orders for the formation of anti-partisan forces that included the specific appointment of Hans Beutelspacher. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC