Apollo Transformed: exploring connections between the collections

From cuneiform tablets to Renaissance and Baroque prints, thousands of gems are nestled in the University of Melbourne. Many of these historically charged yet often whimsical pieces can currently be viewed in Arts West: in the teaching lab, gallery and in the cabinet displays peppered about the building. Taking a closer look at some of the connections between two vibrant collections, I trace the transformations undergone throughout the centuries by the figure of Apollo, the beloved Graeco-Roman god of poetry, prophecy and light.

The classics and archaeology collection of the Ian Potter Museum is the perfect starting-point for our investigation. Here we find a charming bronze figurine of the god Apollo (fig. 1). The figurine is paradigmatic of Graeco-Roman representations of the god Apollo, and of the human physique. In its idealised proportions, swayed hips and contrapposto stance, the figurine reveals its Greek pedigree, harking back to Greek types such as the famous Apollo Belvedere (of which a 2nd century AD Roman copy survives, held in the Vatican Museum). Such Hellenising bronze figurines were extremely popular in the Roman world. Much like the cheaper replicas of antiquities that were brought home by Grand Tourists as proof of cultural refinement, these figures were highly prized by elite individuals, who sought these cabinet pieces as testament to their taste and cultural connoisseurship.[1]

Another example is a small (and quite delightful) Roman statue of Harpocrates (fig. 2), which is currently on display on level two of the Arts West building. The widespread manufacture of these bronzes suggests the extent to which the Greek tradition was admired and emulated in the Roman world and beyond.

Some centuries later, the artists of Early Modern Europe devoted much attention to the surviving art and literature of classical antiquity. Observe, for example, Melchior Meier’s Apollo Flaying Marsyas and the Judgment of Midas, (1581) (fig. 3). This stunning scene draws on two entertaining episodes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (circa 8 AD). The section on the left draws on Ovid’s account of the punishment inflicted on the satyr Marsyas for his boast that his musical talents surpassed those of the god Apollo.[2] Elsewhere, Ovid relates a musical contest between the Arcadian god Pan and Apollo, in which Apollo transforms Midas’s ears into those of a donkey for preferring Pan’s tunes.[3] Meier’s representation skilfully weaves together these two mythological tales, depicting the flayed Marsyas on the left, while the god mocks the donkey-eared Midas with Marsyas’ flayed skin on the right.

Importantly for our survey of Apollo’s guises, the depiction of mighty Apollo in the centre of the engraving shows the unmistakable influence of the Apollo Belvedere, one of the most famous of the classical sculptures that were studied by Renaissance artists. The Apollo Belvedere had been discovered near Rome in the late 15th century, and had become the subject of much interest for Early Modern artists by the early 16th century.

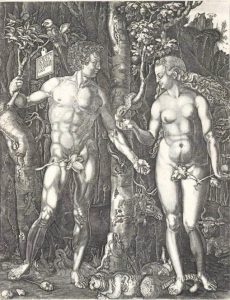

The Early Modern admiration for and adaptation of classical prototypes also emerges in an ostensibly biblically themed work, Dürer’s Adam and Eve (1504). A copy of the work by Johann Ladenspelder is held in the Baillieu Library Print Collection (fig. 4). The poses of Adam and Eve here unmistakably echo those of the Apollo Belvedere and the Medici Venus.[4] Dürer had probably seen the Apollo Belvedere – if not directly, then via an illustrated reproduction – during his trip to Italy in 1494. Comparison with the attitude of the Apollo Belvedere reveals how Dürer has reversed the pose of the classical prototype, removing the Apollonian trimmings of the quiver and chlamys, but retaining the dynamic contrapposto pose and classically idealised proportions. In his famous work Lives of the Artists, contemporary art-historian Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) explicitly mentions the Medici Venus and the Apollo Belvedere, along with other familiar figures such as the Farnese Hercules and the Laocoon, as popular models for Renaissance artists representing human figures.[5]

It is notable that Dürer draws on classical sculptural models even in a biblically themed work. The whole thus epitomises an Early Modern spirit of cultural synthesis. Apollo, in the guise of Dürer’s Adam, has certainly undergone a great deal of transformation compared with earlier representations such as our bronze figurine (fig. 1).

Even when artists of the 16th century began pursuing different approaches to depicting human figures, the classical models were still of central importance. Early modern approaches to representing the body combined detailed study of classical types, and newer understandings of anatomy via dissection. This Early Modern use of both dissected cadavers and classical sculptures for representing human figures is recorded in Enea Vico’s engraving of The Academy of Baccio Bandinelli (circa 1564-61), after Baccio Bandinelli (fig. 5). In this remarkable scene, the engraver has depicted the artist’s workshop as a space for fusing classical artistic theory (represented by the classical statuary in the foreground and above the mantelpiece) and anatomical study of the human body (seen in the dismembered human cadavers and bones shown in the foreground). With its idealised proportions and serpentine silhouette, the figure of a standing male in contrapposto (shown in the lower right foreground) epitomises classical representations of male figures – perhaps even inviting us to recall the image, so familiar to Early Modern artists, of the god Apollo.

Bandinelli’s scene evokes an atmosphere of fervent artistic activity, steeped in the classics and scholarly endeavour. The scene forms a rather attractive backdrop to this survey of Apollo’s journey from antiquity to the Early Modern period. During the course of this survey, Apollo has undergone a great deal of transformation – embodying, in a sense, the evolution of the classics in Early Modern Europe.

Caroline Ritchie, Research Assistant

References:

[1] Hemingway, S. 2002, ‘Posthumous Copies of Ancient Greek Sculpture: Roman Taste and Techniques’, Sculpture Review 60 (2), 26-33.

[2] Tarrant, R. J. ed. 2004, P. Ovidi Nasonis Metamorphoses, Oxford: Oxford University Press, VI, 382-400.

[3] Ibid. XI, 146-171.

[4] Panofsky, E. 1955, The Life and Times of Albrecht Dürer, Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 86.

[5] Vasari, G. (1986), Lives of the Artists, trans. by G. Bull, Middlesex: Penguin Classics, preface to part III.

Leave a Reply