Bursting a bubble: Using prints to teach finance and economics

Just what a hall filled with finance students were not expecting on their first lecture for semester two, was a print curator armed with printed images, historic banknotes and a rare book, set to explain how these items convey financial and economic concepts. Printed material (and by extension other cultural materials) convey economic concepts both in the subjects they exhibit and in the ways they are consumed and used. Additionally, their production often follows trends of financial booms and crashes.

The student’s topic for week one was financial bubbles. A simple description of a bubble is an unstable asset or business accompanied by high speculation. For example, an investor sells commodities or shares worth $100 onto a second investor for an inflated $200 who sells them onto a third party for $400 and so on. Should the company collapse, the original investor makes a tidy profit while the last person into the scheme loses a great deal of money. [1.] The world’s most famous cases and the student’s subjects are: tulip mania, the Mississippi Bubble and the South Sea Bubble.

Tulip mania occurred between 1634 and 1637 and saw the price of tulip bulbs rise to an extraordinary level. Economic bubbles are also characterised by the influence of crowd behaviours whereby people are irresistibly drawn to an asset, such as tulip bulbs, which appear to offer a ‘get rich quick’ opportunity, and a mania ensures. The engraving by Hollar was made in 1641 just a few years after tulip mania. It shows the wealth of the woman who wears an expensive costume and to her right is an open chest displaying a costly fur garment. She holds a bunch of rare tulips (rare striped tulips were affected by the mosaic virus), much sought after by tulip traders and the fashionable. When looking at objects like this engraving, a useful technique to uncover their interpretation, is to ask them questions. For example, when considering an asset whether it is a tulip bulb, a work of art or a company share, how does rarity influence buying behaviours?

The Mississippi Bubble was a more complex financial scheme masterminded by economist John Law (1671-1729). Law became the Finance Minister of France, a country which in 1716 was bankrupt through wars. This provided Law with the landscape with which to launch his economic experiments. The Mississippi Bubble was his misadventure into converting France’s debt into shares of the Mississippi Company, a business focussed on the French colony in Louisiana. Law’s exaggerations of the success and wealth of his company led to wild speculations on its shares. Profits from the shares were issued to investors as banknotes. In 1720 there was a mass urge by shareholders to convert their shares into coin at the bank. However, the Banque Royale did not hold the amount of money represented by the paper notes and was therefore unable to pay. [2.]

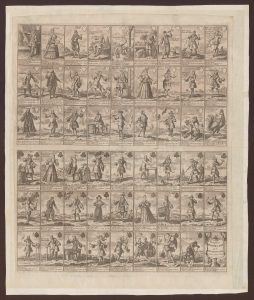

This episode is captured by a new acquisition for the Print Collection: Pasquins Windkaart op de Windnegotie van 1720, an uncut Dutch set of cards satirising John Law and the Mississippi Bubble.[3.] The first card depicts John Law as the King of Hearts and other characters and players in the scheme such as shareholders follow suit. There are many visual references to the Dutch terminology for inflating shares: a ‘wind scheme’, and for selling shares yet to be officially released: to ‘trade in the wind.’ Other financial schemes are referenced, for example the three of spades shows three girls sitting on a swing to represent the South Sea Company, the Mississippi Company and the West Indian Company. As well as an economist, John Law was a gambler and was known to spend his evenings playing cards. These cards are a comical means to enable the disgruntled investor to take their revenge and wield their power upon Law. They seem to ask: how much does chance and emotion play in financial investment?

The engraving Lucifer’s new row-barge satirises Robert Knight (1675-11/1744) and the South Sea Bubble, the second financial crash in England following on the heels of John Law’s experiments in 1720. This, another failed scheme to refinance national debt through a trading company, saw Knight the Cashier abscond with a fortune. Knight stands in a boat bound for hell named the S.S. Inquisition. Various devils and demons control the gold, which is scathingly portrayed in the commentaries as the object of individual and national ruin. Like the cards, this broadside is made by an anonymous artist and would have been sold on the streets of London, the location of an audience ready to revel in sensationalism. It also echoes popular card games for in the top right corner is a playing card which is the knave or jack of diamonds and this card the viewer may associate with Robert Knight.

For contemporary finance students, the 17th and 18th centuries are rather distant and hazy constructs, yet these primary source items provide them with tangible evidence and genuine context. Financial bubbles are as prevalent today as they were in the past and through their example, the Print Collection has now entered the financial arena.

Kerrianne Stone, Curator, Prints

References

[1.] John Chown, A history of money: from AD 800, London; New York: Routledge, 1994, p. 144

[2.] see John Chown, 1994, pp.201-211

[3.] See Roger Tilley, A history of playing cards, New York: C.N. Potter; distributed by Crown Publishers, [1973] especially pp. 123-133.

Leave a Reply