Louise Hanson-Dyer’s Literary Ventures

As learning has become universal so culture has become rare … thus sensitive beauty calls us to pause and be refreshed…

writes Louise Dyer in an article on Rose Adler. This statement on culture and beauty echoes the life work of Dyer and her publishing label l’Oiseau-Lyre and was first made tangible with François Couperin Oeuvres Complètes, a limited collected edition published on the 200th anniversary of the death of Francois Couperin Le Grand in 1933. On 18 & 19 May a symposium celebrating the 350th Anniversary of Couperin’s birth and Dyer’s achievements will celebrate this seminal creation.

Here I shed light on Dyer’s literary aspirations. Along-side her publishing goal of producing rare music Dyer was an avid supporter of Australian writers promoting them beyond the shores of Australia; an initial goal was to have Australian authors translated into French. She was a member of Amis du Livre Français, the Authors and Editors of France and significantly Les Cent Une. The latter was a group of feminists publishing a book each year, the first being Giradoux’s Suzanne et la Pacifique (1927) sumptuously bound by Rose Adler. Dyer also wrote, penning essays on cultural subjects, which, as an attempt to bridge the cultural and distance gap, she sent back to Australia to the Melbourne Herald newspaper, one a series Impressions of France. During her life she formed close working relationships with writers, such as Joyce, Duhamel and Innes just to name a few.

Dyer was a Francophile but at heart she was still Australian. Evidence of this was her return to Melbourne on 11 January 1932, to support her unmarried brother, Gengoult Smith, who had been elected Lord Mayor, as his Lady Mayoress. During this trip she was invited to present a paper to the Australian Literature Society (ALS). She suggested that she should speak on the ways Australian authors might be promoted internationally. To that end a committee was set up to suggest a list of suitable works. Dyer returned to Paris and began liaising with French publishers. However, reservations were expressed by several authors on the list when told that adaptations rather than direct translations were being considered by the French publishers. Kate Baker, copyright holder to Furphy’s Such Is Life thought the French would appreciate its ‘literary flavour’, but when cuts were suggested, Baker lost interest, and no further correspondence was received. Barnard Eldershaw (Marjorie Barnard) author of A House is Built was also “rather adverse to there being any cutting or adaptation of” her work. Miles Franklin was concerned that Aussie slang may not translate well!

This set-back didn’t deter a tenacious Dyer. Another opportunity to proceed came alongside the Centenary Celebrations for Melbourne for 1933/34. A perfect opportunity to consider a literary competition, Dyer foresaw the winner having their novel translated into French, therefore promoting Australian literature to the world. In a letter to Major Condor of the Celebrations Committee (7 April 1933) Dyer explicated her instructions for the competition – importantly there should be a woman amongst the judging panel. Dyer offered a prize of £200 for the winning novel and prizes for poetry and a short story.

Regrettably the competition became farcical and strains of nepotism were evident. Vance Palmer was expected to win first prize for his novel, The Swayne Family, but his wife Nettie was an acquaintance of Dyer’s from her Presbyterian Ladies College (PLC) days. In the event, and much to his chagrin, he had to share with F.S. Hibble’s Karangi; he did, however, win the short story section. In an obvious conflict of interest, Frank Wilmot (Furnley Maurice), who had been on the novel judging panel won the poetry prize for “Melbourne and Memory”, one of his Melbourne Odes. Dyer was very disappointed that none of the works could be unequivocally promoted as ‘the Australian novel of the hour’ – we can only ponder what Dyer had in mind as an exemplar. Translations into French and publications never eventuated.

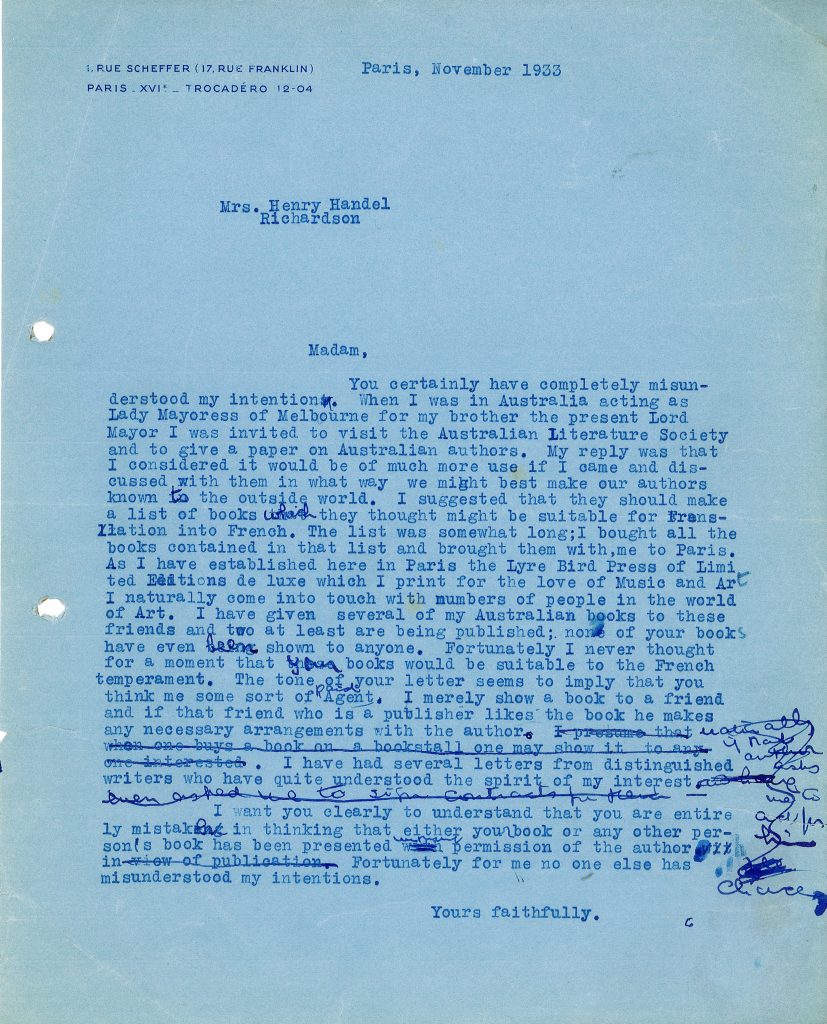

Dyer’s disappointment became frustration when her intentions were misconstrued. This is starkly illustrated in a somewhat scathing reply (in draft form) from Dyer to a letter, now lost, from Henry Handel Richardson (HHR), another ex-PLC student. Richardson had obviously completely misunderstood Dyer’s intentions thinking that a book of hers may have been presented to French publishers without her permission. Louise bluntly replies that none of HHR’s books had ever been shown to anyone, and adds in a tone of complete disparagement, “Fortunately I never thought for a moment that your books would be suitable to the French temperament”! (November 1933)

This outburst might have been an understandable response but is at odds when we consider that they shared ideas about promoting Australian ‘culture’ to an international audience. HHR stated in an interview with the West Australian newspaper, “I always wanted to do something for Australia.” In 1930 HHR was awarded the ALS medal for best Australian Novel of 1929 Ultima Thule. With obvious commonalities it is unfortunate that HHR had asked for much of her correspondence be destroyed after her death. She “…. dreads curiosity about one’s personal life”, writes Palmer in The Australian Women’s Weekly, when interviewed on her biography of HHR; ironically conjecture can thrive where proof cannot be found.

Further reference to Dyer is mentioned in correspondence between HHR and another former student of PLC, Mary Kernot (16th February 1932). It has a somewhat perfunctory element of envy and trivialisation:

I seldom go to any receptions to celebrated people but I was at one yesterday to welcome Mrs James Dyer. She is a daughter of the late L.L. Smith and now lives in Paris and spends her time on musical affairs reviving old music & having it printed on a press of her own. She has plenty of money & is a rather elegant creature with yesterday a little hat perched on top of waved tresses …

These back-hand affirmations are part of the psychology of the Australian habit of the Tall Poppy Syndrome, perhaps. The PLC network had the ability of promoting Australians publicly but alongside insidious elements of cutting individuals down with scathing comments and self-deprecation. The contradictory mood is summed up by Kernot “It would be a triumph for this country. But alas we are like the ants, a little folk.” Dyer dismissed this prognosis through her actions and dissolved the distance between an historical Europe (culture) and a colonial outpost (culturally bereft) by feasting on the symbiotic relationship between poetry and music.

Works Consulted:

Australian Women’s Weekly (9 September 1950 p. 18).

Chanin, Eileen and Miller, Steven “The Patron Louise Dyer (1884-1962)” in Awakening: Four Lives in Art (Wakefield Press 2015).

Davidson, Jim. Lyrebird Rising: Louise Hanson-Dyer of Oiseau-Lyre 1884-1962 (Melbourne University Press at The Miegunyah Press 1994).

Probyn, Clive & Steele, Bruce. The Letters Volume 2 [1917 – 1933] (Miegunyah Press 2000).

Editions de l’Oiseau-Lyre Archive (Rare Music, Special Collections): 2016.0035.00220; 2016.0048.0002; 2016.0048.00011.

West Australian “Interview with HHR” (21 March 1931 p. 4).

Dr Nigel Abbott

Research Assistant

Editions de L’Oiseau-Lyre archive

Thanks for this… having acquired a copy of Karangi I am exploring the web for references to it, and found this fascinating.