New Year, New You!

At the beginning of a new decade, it seems important to reflect on what aspirations we have not just for ourselves as individuals but also for our collective species. What do we place the most value on in Western culture today? What signifies an individual’s worth? It is undeniable that physical beauty is associated with success and wealth in contemporary society but without questioning where and when this association might have originated, it dangerously becomes the assumption that beauty has always been symbolic of accomplishment or that to achieve something, one must be beautiful.

To many, it seems that placing such value on physical appearance is somehow an unavoidable, innate quality of human beings – perhaps it has even been framed as a necessary trait for our species to differentiate from other animals and progress our civilisation via our ability to conceptualise beauty. But this obsession with the aesthetics of the human body and the widespread dissemination of images that project an ideal of beauty to the masses only began around the time of the Industrial Revolution, during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

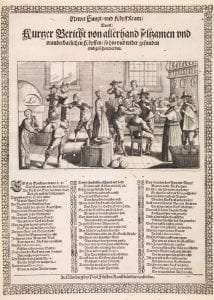

The University’s Print Collection contains an absurdist satirical broadsheet (c. 1650), which was created prior to this era, with a darkly comical engraving titled ‘The Shop for New Heads’. Its featured image shows insecure and gullible civilians, dissatisfied with their current facial appearances being decapitated. Whilst this strange practice occurred, cabbages were placed at the top of their necks to stop them bleeding out. This gory scene references a legend that was popular during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in parts of central Europe about a bakery in a Flemish town called Eeklo where people could go to have their detached heads made more aesthetically pleasing by sprinkling them with flour, glazing them with egg yolk and baking them in an oven, to then be reattached once they had been ‘improved’.

The legend tells that the heads never quite baked through, leaving those who had chosen to partake in this procedure with a permanent deformity. At the time, this broadsheet would have served as soft propaganda to persuade people to be satisfied with what body and situation they were born into. Whilst its message is not necessarily one we should be adopting entirely now, what this piece of seventeenth century ephemera shows us is that societal attitudes surrounding beauty change rapidly and are often as arbitrary and strange as the tale of the Baker from Eeklo.

Today, with the global beauty industry valued at over $500 billion, it’s hard to imagine a message promoting satisfaction with one’s body being celebrated when it’s proliferation would have drastically negative effects on a huge sector of the global economy. It might be easier to conform than to challenge the status quo but we should ask ourselves who those standards of beauty are serving.

In an educational and institutional context, we have an abundance of resources readily available to us that can serve as catalysts for new ways of thinking about the world we live in. Within the archives and cultural collections, there are many items that are yet to be thoroughly researched and many that could be reexamined and understood anew. And is the acquisition of knowledge itself not a beautiful thing?

Ana Jacobsen

Special Collections Blogger

Ana is currently studying a Master of Creative Writing, Editing and Publishing

Categories

Leave a Reply