Plotting a course for object-based learning with exhibitions

Object-based learning classes where students engage directly with cultural materials may take many varied formats either in a class room, a collection store or an exhibition space. When I prepare the works of art from the Print Collection for a class in the Leigh Scott Room in the Baillieu Library, I often experience the unexpected problem of chairs. This utilitarian item is usually the first physical object students encounter in the room before they engage with the rare prints. With such capable students at the university, I will indicate the stack of chairs with a ‘please help yourself.’ This immediately raises a problem for students who ask, ‘where do I put it; which orientation does it face; how is it to be arranged? These are also the kinds of questions I have also asked myself in relation to the preparation of the university’s cultural collections. To avoid this vexing class challenge I have also laid out the chairs prior, only to have the students stand up amongst the chairs reverentially, being careful not to touch them. If the same chair were to be placed in say, a café, the student’s relationship with it might be quite different to that of the chair-of-the-cultural-institution. There are many suppositions to be read into ‘the problem of chairs’ example, but powerful for me is the influence of the physical environment, our preconceptions and those of our peers, on our interaction with cultural objects.

Fortunately in exhibitions, students are able to move around in the space and interact with objects; therefore they are less likely to sag to the ground and are able to forego the ubiquitous class chair. Object-based learning with exhibitions is a powerful experience, offering an environment of evocative objects which have been carefully arranged into a context, ready for diverse responses and interpretations.

Students from such disparate disciplines as Astronomy in World History, Australian Art, Global Literature and Postcolonialism have all engaged with the latest exhibition in the Noel Shaw Gallery, Plotting the island: dreams, discovery and disaster. Asking an object a question, even a simple one, such as, ‘which orientation does it face?’ is a very effective means of revealing the secrets of its materials, purpose and history and hence how it speaks to our society.

After a tour of the exhibition to briefly hear key themes, the students from Global Literature and Postcolonialism broke into groups, looked at and discussed objects in relation to two very broad questions. One group looked at objects in terms of their authenticity, and this all depended on how they interpreted the term ‘authentic.’ The other group examined the objects to consider a narrative from another perspective; a narrative that was ‘missing’ from what was presented. They came up with very considered and thought-provoking observations.

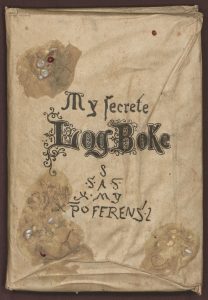

An object which very obviously challenges ideas of authenticity is the book, My secret log boke. This volume claims to be the lost journal of Christopher Columbus found in a chest on the coast of Pembrokeshire 400 years after his death. The students immediately noted that the appearance of the book was odd, and looked deeper to see that the materials had been manipulated. The paper and writing on the cover did not ring true, nor did the sea shells that were glued on. The students then began to question whether the tone and expression of the language used were authentic to the era and stature of Columbus.

Yet the students grappled with other aspects of authenticity, almost shocked that an authoritative document like a map could contain information that was not absolutely accurate, such as a landmass that did not exist or a coastline that was incorrectly drawn. Or similarly, that a contemporary artist had changed the meaning of a historic portrait of Joseph Banks with the addition of villainous Big Bad Banksia Men. The accuracy of the information presented became a key approach to validity, but they came to recognise that authenticity is relevant to particular times in history and modes of thinking and there were no absolutes in its application.

The group investigating alternate narratives were drawn to the navigational instruments. To them these Western artefacts did not acknowledge the skilled reading of stars and navigation history of Indigenous peoples. The chronometer for example, represents a breakthrough in the development of Western navigation in the way it enables the calculation of longitude. The students said that the development of Indigenous knowledge was not shown and that the objects, by their physicality, did not recognise the long oral and ephemeral expert traditions of non-Westerners.

Another object these students gravitated to was the scene depicting the massacre of members of the La Pérouse expedition. Jean-Francois de Galaup La Pérouse quite literally went missing in 1788 after his departure from Australia. Previously, in 1787, after stopping for water on Tutuila, Samoa, a party from the expedition were attacked and killed by the islanders. The students thought this image implied the explanation of La Pérouse’s fate; that he had likewise been violently attacked in the Solomon Islands, the location of his ship’s wreck. One student noticed the women in this etching, placed on the margins. The women’s role or even their nationality was not apparent; their presence had been rendered ambiguously in the narratives.

The skill of looking is fundamental to object-based learning. With my background in visual arts, I had to learn how to read a historic map; while they utilise precisely the same materials and technology as a more familiar print, the ideas they communicate are radically different. Object-based learning is also a lesson in looking and of not allowing what you see to fall within a frame of expectations and preconceptions.

Kerrianne Stone (Curator, Prints)

Categories

Hello! I am very interested in the above, because I have an identical copy of the “Secrete Log Boke”, together with a copy of the letter purporting to be from the fisherman who found the “Boke”. I inherited the “Boke” when I cleared a deceased relative’s house, and would love to know what its origins are! How did you come by it?

Best regards

David Robinson

Hi David, thank you for your comment. The Baillieu Library copy of “My secrete log boke” was one of the 2,500 books gifted by George McArthur.