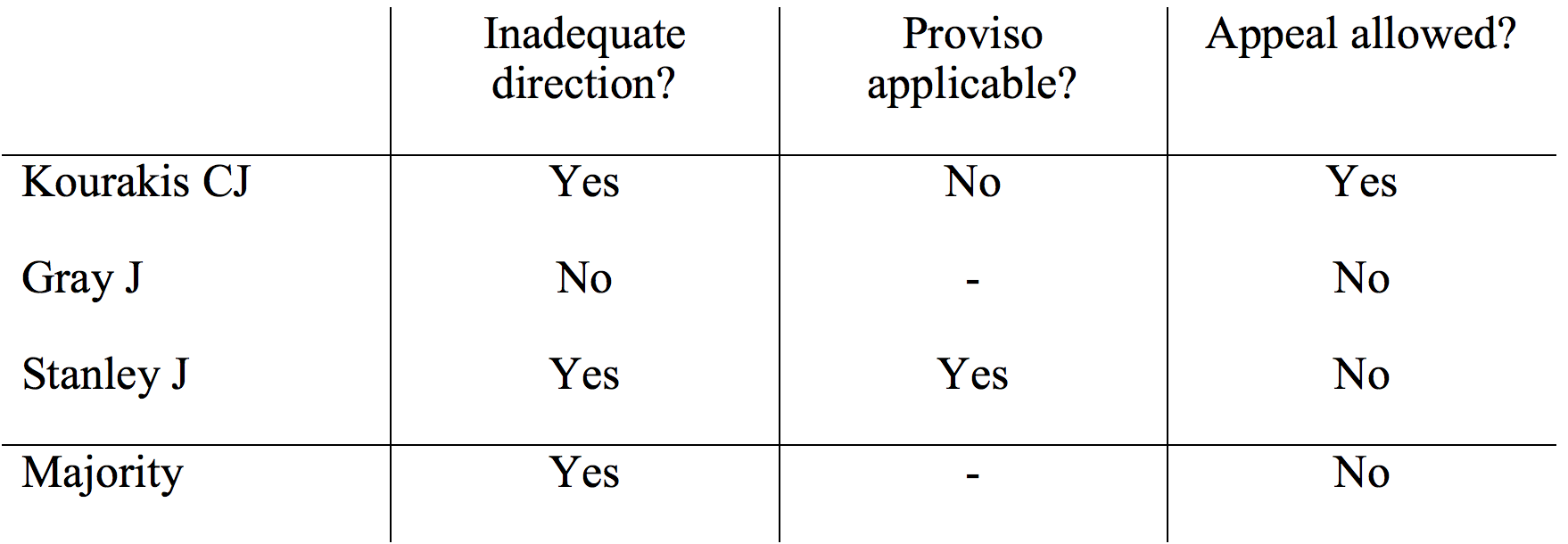

Today’s decision in Perara-Cathcart v The Queen [2017] HCA 9 reviews a split decision in the Full Court of South Australia’s Supreme Court, which Gageler J’s judgment usefully describes with a table:

This combination raises a long-standing puzzle about the judgments of multi-member courts that have to decide two different issues in a particular case and manage to produce a three-way split. (See here for discussion of another example.)

In this case, the two issues were whether the trial judge erred (specifically in directing the jury) and whether the error was substantial enough to require a new trial (a question referred to in Australian law as ‘the proviso’.) Justice Gageler describes this puzzle as, it applies to South Australia’s appeal statute, follows:

Is there one big question as to whether the appeal against conviction should be allowed or dismissed under s 353(1) and, if allowed, as to what consequential direction should be made under s 353(2)? Or do two questions arise sequentially under s 353(1): the first as to whether the

Full Court thinks that the verdict of the jury should be set aside on one or more of the three identified grounds, and the second question as to whether the Full Court considers that no substantial miscarriage of justice has actually occurred?

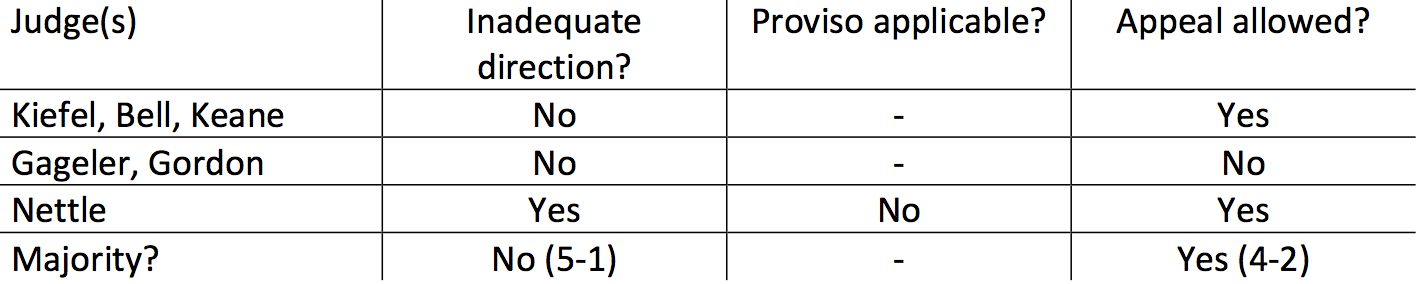

Two judges (Gageler and Gordon JJ) decided there was just ‘one big question’ while the remaining four judges (the plurality and Nettle J) decided that there were two.

But, the High Court granted leave (actually a notice of contention from the prosecution, disputing the reasoning of the court below despite agreeing with the result) on the two issues that were before the South Australian court too. Interestingly, this resulted in the six member court splitting three ways. Here (Gageler J-style) is how the three questions (the two issues, and the multi-member court issue) panned out for the six judges:

Fortunately, the Court’s three-way split was easily resolvable. While a 4-2 majority thought that, given the findings the three judges made, the South Australian court should have allowed the defendant’s appeal, a 5-1 majority also found that Gray J was right to find that the direction to the jury was adequate (and, like Gray J, that meant that they didn’t have to determine whether to apply the proviso.) Only Nettle J thought that one judge below (Kourakis CJ) correctly found in favour of the defence on each point, so he was the only judge who would have allowed the appeal. It’s the 5-1 decision that determined the High Court’s order, dismissing the case. The 4-2 ruling is mere (quite well considered) dicta.

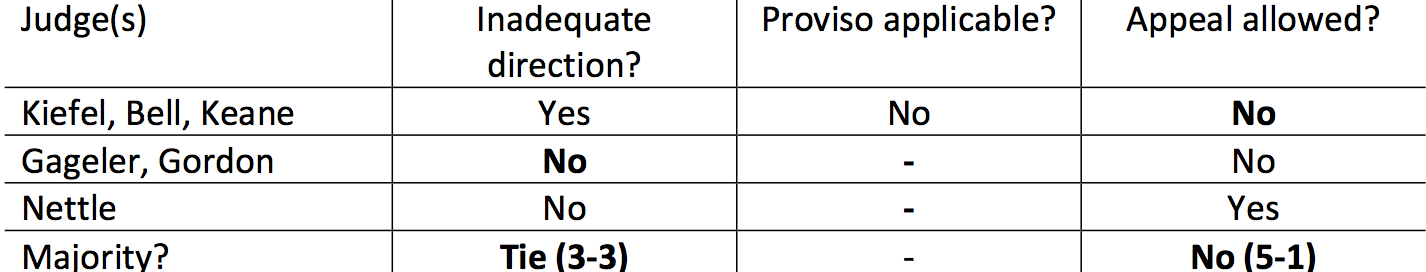

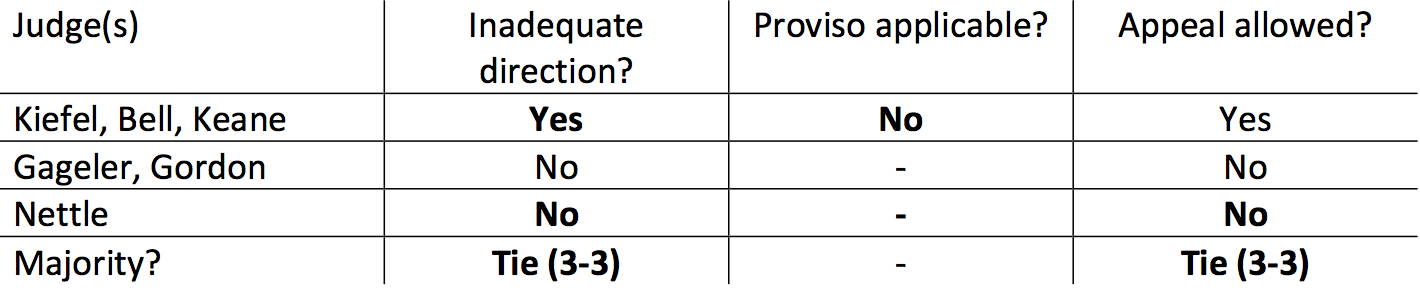

And now some multi-judge puzzles for you at home. What if the High Court judges had made the following findings (variations from today’s decision noted in bold)?

In each instance, would the High Court’s order have been ‘appeal dismissed’ or ‘appeal allowed’? (Note that ‘appeal allowed’ in each table is about what each judge thought the South Australian court should have ordered, given the split in that court, not what each judge thought the order should be in the High Court.) Feel free to leave your answers (and any suggested variations of your own) in the comments.