Yes Mr Gardner. Your Honour, I wanted to rise at this stage to urge Your Honour to consider giving a Prasad invitation to the jury.

Narendra Prasad is one of the unlucky Australians who have a rule of law named after them. But his rule isn’t really a rule, just some dicta (passing judicial commentary.) And it isn’t a really a law, just a practice that judges can choose to use in a criminal trial if they want to. As well, as of last month, it’s a practice they can no longer choose.

Prasad’s brush with the law began with a site at Adelaide’s West End where a Banh Mi shop now sits underneath one of the city’s ubiquitous Polites signs. In between the 1960s (when it was a Scientology HQ) and the 90s (when it was a lesbian bar), the address hosted a string of restaurants: The Brussels, Cedars, Tripoli, Fagans, Rogues, Bandito’s, Katz, and Out. In August 1974, Praspen Estates Pty Ltd, a company Prasad cofounded the previous year, bought Cedars, but he soon sold the company to the restaurant’s owners. Alas, in 1978, Victoria Penley, the other co-founder of Praspen (and the portmanteau’s other half), told police that Prasad sold their company without her knowledge. Prasad was charged with obtaining $7000 from Cedars’ operators under the false pretence that he owned their restaurant outright.

The prosecution’s case against Prasad rested on two witnesses. One was the company’s then lawyer, who contradicted Prasad’s story to the police that Penley gave up her shares because she didn’t want to own a restaurant; however, the since debarred Tennyson Turner’s credibility was, to put it mildly, under a cloud. The only other witness was Penley herself. She denied any transfer, but at times seemed to concede that her husband managed such things for her:

Is it a possibility that you could have signed this share certificate to transfer the shares back to Mr. Prasad and you have now forgotten about it, or didn’t notice at the time-isn’t that just a possibility? I don’t think so. But isn’t it a possibility? It could be.

Penley’s husband was not called to testify.

If that strikes you as a fairly thin basis to convict someone of false pretences, you aren’t alone. At the end of the prosecution case, Prasad’s lawyer, Kevin Borick, asked for the charge to be thrown out, but the trial judge and later the full court of South Australia’s Supreme Court ruled that Penley’s testimony was capable of supporting Prasad’s conviction. Nevertheless, two of the full court’s judges, including Len King, the state’s feted Chief Justice, noted that trial judges aren’t limited to either throwing a charge out or letting the trial continue. They have a third option: letting the jury choose whether to acquit immediately or hear the rest of the case.

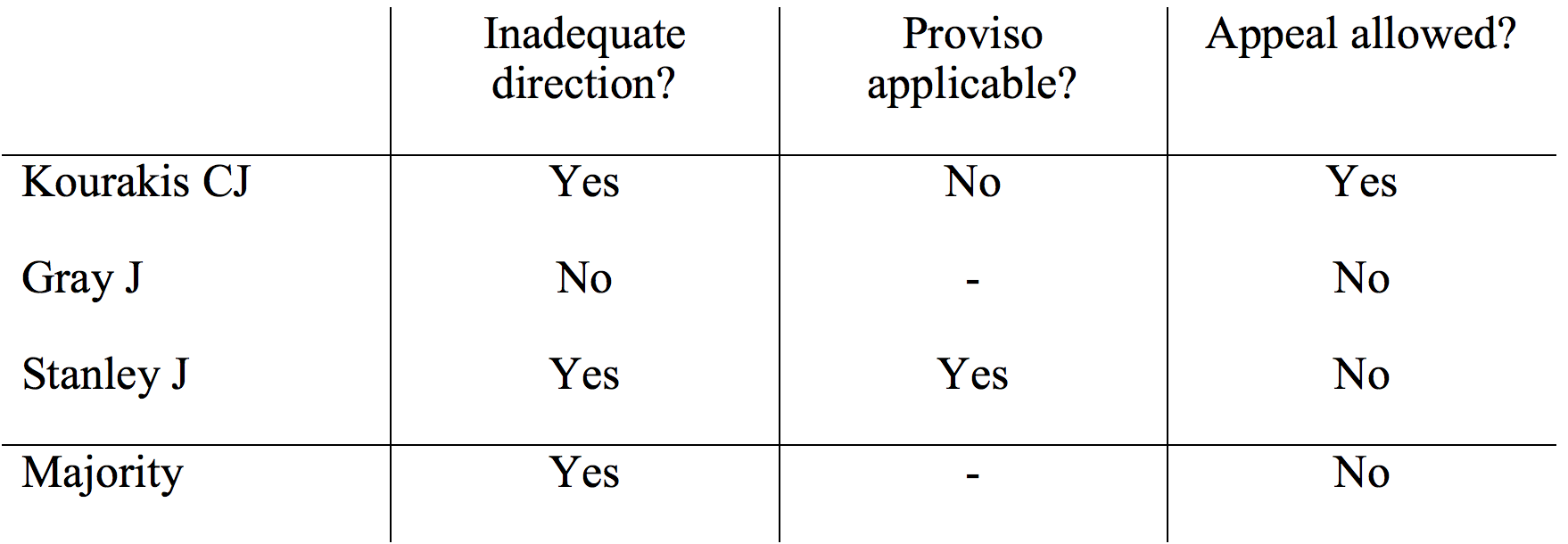

Just four years later, that option – which was neither sought not used in Prasad’s own trial – was mentioned for the first time in the High Court. Justice Dawson, joining a unanimous ruling overturning a South Australian indecent assault conviction where the prosecution chose not to call the complainant as a witness, observed that the trial judge had refused the defendant’s request to give the jury a ‘Prasad invitation’. In 2006, the practice was mentioned again in the High Court by Chief Justice Gleeson, when he joined a unanimous holding that a NSW trial judge prejudged whether or not to throw out a protection racket charge at the end of the prosecution case. Neither Dawson J nor Gleeson CJ expressed any reservations about the practice, which received its third and last High Court mention last month in a Victorian case. In Director of Public Prosecutions Reference No 1 of 2017 [2019] HCA 9, a unanimous joint judgment ruled the practice ‘contrary to law’.

Mr Gardner, you know, I take it, that the direction, if I give it, will be offered to the jury in the context of them only having an option to acquit or to indicate that they want to hear more. Yes, I’m aware of that, Your Honour, and I’ve got an instruction to make this application.

There is a set order in criminal trials in an adversarial justice system like Australia’s. First, the prosecution gives an opening speech to the court and then the defence does. Then the prosecution presents its evidence (witnesses and the like) and then the defence can do the same (or not.) Next, the prosecution gives a closing speech and the defence can too. If there’s a jury, the trial judge will speak to them last. Finally, the verdict.

A fraught question in criminal procedure law is whether and when to deviate from this set order. Sometimes the variations are small ones – slight changes to the order of events, delays and the like – to cope with life’s and the law’s exigencies, matters that all trial judges must deal with ad hoc. But the Prasad issue is part of a much harder question: whether, when and how a trial should stop early if the prosecution case falters. This question pits the criminal justice system’s adversarial nature (where both sides play similar roles) against its accusatorial nature (where the burden of proving guilt falls on the state alone.)

One view is that criminal trials should never end early. In apartheid South Africa, for instance, trial judges were obliged to continue even after the prosecution case failed to prove an element of a crime, because of the possibility that the defence may nevertheless be bungled in a way that convinces the court of the accused’s guilt. But that rule is roundly rejected nowadays as inconsistent with the accused’s right to remain silent. Another view, taken in England, is that trial judges can stop a trial if the prosecution case is really weak because of bad, vague or inconsistent evidence. In 1990, the High Court (following earlier Australian courts, including South Australia’s in the Prasad case) rejected that view. The only situation where an Australian trial judge can stop a jury trial early is ‘if there is a defect in the evidence such that, taken at its highest, it will not sustain a verdict of guilty.’ Accordingly, it dismissed an appeal by a drug trafficking accused whose trial continued despite the main prosecution witness admitting to repeated lies to the police.

Australia’s rule allows some very flawed trials to continue through to the end. A startling recent example is a murder trial where the main evidence that the accused killed the victim at an isolated rural property was from a man who had moved in with the pair six weeks earlier. As he testified about discovering the accused standing over the victim’s bruised body, the accused shouted from the dock ‘it’s not true’, prompting the following statements by the witness (with Justice Richard Button intervening):

Who said that, how do you know it’s not fucking true I was there. Just a moment, sir. Just answer the questions that the prosecutor asks and then we’ll get through the process. It’s fucking true, Gary. Just a moment. It’s so fucking true, you gronk. Just a moment, sir. We can’t have people yelling out in court, neither you nor him, otherwise we are not going to get through the process. Fucking murdering cunt. Take a moment and then we’ll– I should have fucking killed you too you cunt.

Now, it’s not every trial where the main prosecution witness seemingly admits to being the actual murderer in open court. And this was just one of numerous bad moments for the prosecution, including Button throwing out all the admissions the accused allegedly made to the police. Button later declared: ‘Since an early stage of the Crown case, I have considered that there is a significant possibility that an innocent man has been arrested, charged, incarcerated for almost exactly 4 years, and ultimately arraigned’.

And yet, consistently with the High Court’s ruling in 1990, he observed: ‘there is certainly some evidence implicating the accused in the death of the deceased; it is no doubt for that reason that no application was made for a verdict by direction by defence counsel’. Instead, the judge – who was deciding the facts without a jury after the accused was found unfit to stand trial – gave himself a Prasad invitation and acquitted the accused, declaring that the ‘continuation of this state of affairs is not to be countenanced’.

And yet, consistently with the High Court’s ruling last month, if the trial had happened just one year later, that state of affairs would have had to continue until the trial ended or the prosecution gave up. In urging the High Court to ban the Prasad process, Victoria’s Director of Public Prosecutions suggested that problematic cases could instead be dealt with by the judge urging the prosecutor to withdraw the case. She added that ‘such circumstances will be rare and should only occur where the issue as to sufficiency of evidence is glaringly obvious’.

Dr Rogers. There’s nothing before the jury about what precisely happened in the unit on the night of the 18th of July 2015. I agree. And in my submission that’s the short answer about why a Prasad direction should be resisted by Your Honour. As Your Honour pleases.

The case that led to the High Court banning the Prasad process is a less rare type of trial where the flaws of the prosecution case are less glaringly obvious: domestic homicide trials where the evidence reveals the deceased’s violence towards the accused.

In July 2015, Gayle Dunlop called the police to report that her long-term partner, John Reid, was bleeding from a fall. In fact, she had struck him with a timber footstool and he died a few days later. The prosecution led evidence of events leading up to Reid’s death that made it clear that Dunlop was the victim of domestic abuse. Her sister and daughter described seeing her bruises and being told ‘It’s none of your business and you know what goes on’. Another witness told of her explaining in front of Reid, a few weeks before he died, that she’d had a fall but later confiding: ‘I think he’s going to kill me’. Two police officers described being called to the couple’s house not long after to remove him at her request. On the night Reid was injured, neighbours heard a heated argument where Reid called Dunlop ‘you whore’. After her emergency call, forensics found her blood at the scene. When she was arrested that night, police initially ignored her requests to speak to her sister. When she finally did, she told her ‘You don’t know what I’ve been through’.

When Dunlop’s barrister Shane Gardner asked for a Prasad invitation at the close of the prosecution’s case, Supreme Court Justice Lex Lasry was initially dubious. He pointed out how such cases often cause public controversy, mentioning a 1979 Victorian case where the reigning Miss Australia and her son were acquitted of the shooting murder of their husband and father, William Krope, after testifying about his violence and perversions. He noted that Victoria’s current law on the issue was complex and he would need to tell the jury about the fault elements of both murder and manslaughter and the recently amended law on self-defence. Gardner observed that Lasry himself had given a jury a Prasad direction in a complex (but different) homicide case a decade earlier, but the judge reflected on how he had experienced the ‘pitfalls’ of such directions as both judge and counsel, perhaps referring to how the jury in the earlier case ultimately convicted the accused of manslaughter.

Last year, New South Wales’s Justice Richard Button (two months before he gave himself a Prasad direction to end the domestic homicide trial described above) declined to give a Prasad direction to a jury in a still more extreme domestic homicide trial. Not only did the prosecution present multiple witnesses who testified to the deceased’s violence in several relationships and his extensive criminal record, but their case was that the accused fatally stabbed the deceased at the same time as he fractured her skull with a domestic clothes iron. Button’s reasons for declining to use Prasad were similar to those raised by Lasry eighteen months earlier: the complexity of the directions and the fact that self-defence raises not only factual but ‘normative’ considerations about what actions are reasonable:

As I remarked to counsel in discussing the application, such a question perhaps raises all sorts of “sub-questions” about the availability of alternative ways of protecting oneself; about how life is in an outback town as opposed to an urban centre; about possible alternative ways of getting help within an extended relationship marred by domestic violence; and countless other social matters. In short, I felt uncomfortable, with regard to that evaluative judgment, about providing even a “hint” to the jury as to how it should be determined; and, no matter how one expresses it, in my experience that is always how a Prasad invitation is received by a jury.

But the trial soon collapsed completely. Immediately after Button’s decision, the prosecution conceded that the murder charge – brought despite a magistrate refusing to commit her for that crime – was never sustainable. Then, after several defence expert and character witnesses testified, the prosecution responded to a renewed request for a Prasad direction on the remaining manslaughter charge not only by supporting it, but urging the judge to simply tell the jury to acquit the accused. A flabbergasted Button complied and later ordered the prosecutor to pay the accused’s costs for the trial.

Ultimately, Lasry opted to give Dunlop’s jury a Prasad direction, noting that Victorian law now includes a lengthy provision requiring jurors to fully consider evidence of family violence. After his direction, the jury deliberated for an hour and then returned to say: ‘We would like to hear more evidence.’ Lasry responded: ‘It’s not a now or never. The choice that I offered you this morning is a choice that you can make at any time before the trial concludes’.

Bearing in mind your very economic submission, it is the fact that after the close of the prosecution case the jury has a right to acquit. Yes, Your Honour. What we’re discussing is whether they should be informed of it…

For decades, Canadian judges believed that they could never stop a jury trial themselves. Rather, their practice in cases where the prosecution evidence was inadequate was to tell the jury: ‘Since the accused have been placed in your hands, it is not for me to acquit them. It is for you to do so’, before directing them that the accused is legally entitled to an acquittal. This lasted until a case reached the Supreme Court of Canada where a juror replied: ‘I don’t think all of us think that it’s not guilty. Sorry. Some of us still believe a guilty verdict should go through.’ The juror explained that some of them felt it wrong that they spent four weeks on a case without making a decision. After the judge told them he was happy to discuss the issue, but it had nothing to do with the verdict, the jury acquitted the accused. The Supreme Court responded by modifying the practice so that judges would enter the not guilty verdict themselves.

But what about the opposite situation? In a 1903 English trial, after the prosecution case had closed and the defence started calling its witnesses, the jury stopped the hearing and returned a verdict of ‘Not guilty’. The prosecutor said he wanted to address the jury but the judge told him ‘Your case is finished, and, that being so, the jury are entitled to exercise their right at any moment afterwards to say whether the case has been made out or not.’ Unsurprisingly, an identical practice to the Prasad direction – albeit without the catchy name – has long been and remains part of English law. In 1987, Hong Kong’s Court of Appeal, in response to a prosecutor’s reference, ruled: ‘Yes, there is a right in a jury to acquit an accused at any time after the close of the Crown’s case on the whole or any of the counts in the indictment.’ Citing Prasad itself, the Court of Appeal concluded that a judge has a duty to end a case in some circumstances and power to inform the jury of its right to do so in others, albeit ‘only in the rarest cases and after receiving submissions from counsel.’

The right to acquit ‘at any time’ has affinities to two other better established, albeit sometimes controversial, parts of court practice. One is the High Court’s own recurrent practice of stopping hearing a case after one side concludes its arguments. The Court exercised that power the same week it ended the Prasad direction, telling the parties to a constitutional challenge that it no longer wanted to hear arguments on part of that challenge. The second is what Americans call the jury’s right of ‘nullification’ and English courts call a ‘perverse verdict’, where jurors acquit in face of the evidence and the law. A famous Australian example occurred in Adelaide several years after Prasad’s trial. In a murder case, where the accused killed her sleeping husband with an axe after discovering that he had been raping their daughters for years, the jury were told that their options were to convict the accused of either murder or manslaughter. They returned and asked how to acquit the accused completely. Two hours later, they did so, to widespread public approval.

Whatever the current status of those rights in Australia (and, indeed, the right of judges deciding alone to give themselves a Prasad direction), the High Court ruled last month that Australian common law ‘does not recognise that the jury empanelled to try a criminal case on indictment have a right to return a verdict of not guilty of their own motion’. The Court dismissed the early English cases on such a right as historical relics and more recent ones as sloppy references to a mere right to act on a trial judge’s invitation. (The justices were seemingly unaware of the Hong Kong ruling.) Rather, the Court held:

It cannot be that the jury possess a personal right to acquit at the close of the prosecution case regardless of the issues that arise for their determination. In cases of legal or factual complexity, a jury may not be able to return a “true verdict”, consistently with the oaths taken by each juror, without the assistance of addresses and the judge’s instruction on the applicable law.

The High Court identified a further problem in trials such as Dunlop’s where more than twelve jurors are empanelled to allow for attrition during the trial. It deemed Lasry J’s decision to ballot off the extra juror while the jury considered the Prasad direction and then having the extra juror rejoin the jury to be ‘a serious departure from the proper conduct of the trial’, apparently because of the possibility that returning juror might hear what the other twelve discussed in private. The Court made no reference to proposals by the NSW Law Reform Commission to put the process Lasry J improvised on a statutory basis or by the Victorian Law Reform Commission to allow enlarged panels of jurors to deliberate on the verdict.

Yes. I meant the important thing is whether or not the original judgment of Chief Justice King in Prasad remains the law and as far as I’m aware it does. Yes, Your Honour.

Dunlop’s defence called two witnesses, a family violence expert (whose testimony was pre-recorded) and Dunlop herself. After the defence case closed, Lasry told the jury that they would now be addressed in turn by the prosecutor, Nanette Rogers, the defence lawyer, Shane Gardner and then himself; however, he also reminded them that their earlier option to acquit at any time stood. The foreman promptly asked for ‘ten minutes’ and (after a juror was again balloted off) the rest returned twenty-two minutes later with a not guilty verdict. The trial – and Gayle Dunlop’s trials – was over.

But Victorian law means that prosecutors can – and did – ask the Court of Appeal to rule on questions of law after a person is acquitted. And that case could – and did – proceed to the High Court because of the Mason Court’s overruling of the Dixon Court’s ban on the High Court getting involved in such matters, over Brennan J’s lone dissent that allowing the Court’s jurisdiction to be invoked in this way:

enhances the influence of the Executive Government on the development of the law and thus diminishes the characteristic capacity of the courts to give an unprejudiced ruling to determine the rights and liabilities of subjects in controversy with Government. To compromise the courts in the discharge of that role is to diminish the guarantee of a free society. In my opinion, so serious a tampering with a constitutional safeguard is not to be justified by pragmatic considerations favouring the declaration of points of law that have been misunderstood.

(The correctness of the Mason Court’s ruling, and its compatibility with the later doctrine barring courts being given powers that compromise their institutional integrity, was not raised before – or by – the Kiefel Court.) In contrast to Hong Kong’s Court of Appeal in 1987, which upheld the Prasad practice in that country but criticised its particular application in the court below, the High Court (at the DPP’s urging) made a blanket ruling that the entire practice ‘contrary to law’ while barely considering Lasry J’s own decision.

Having held that jurors do not have a right to acquit at any time but only when invited to do so, the Court’s reasons simply balanced the pros and cons of the practice of giving the such an invitation mid-trial. According to the Court, the cons are many:

In summary, the jury are deprived of the benefit of addresses by counsel and the judge’s summing-up; provisional views about the acceptance of a witness’s evidence may be hard to displace; juries are often keen to register their independence and may react against perceived pressure to acquit; the practice is inherently more dangerous in a complex case or one with multiple accused; the prosecution or defence may not have the opportunity to correct a mistaken understanding of their case; and there is a danger, in a case in which the defence is contemplating not calling evidence, of asking the jury if they want to hear more.

The pros, on the other hand, are few: ‘The saving of time and costs, and restoring the accused to his or her liberty at the earliest opportunity’, which the Court deemed minor in straightforward trials. Accordingly, the Court announced the practice ‘contrary to law’ (at least in jury trials.)

Like the pronouncements of jurors and legislatures, the reasons for blanket rulings by the High Court – ones whose terms don’t allow them to be distinguished in future cases – don’t really matter now. It certainly doesn’t matter that the Court made no mention of (and may well be wholly unaware of): Dawson J’s and Gleeson CJ’s earlier (uncritical) observations on Prasad invitations; the mid-trial practices of any common law country beyond England and Australia (including the contrary ruling by Hong Kong’s Court of Appeal); the recommendations from two Australian law reform bodes on how to manage oversized jury panels in such contexts; or the seemingly lingering issue of whether and when trial judges acting without a jury can stop a trial early. It is unlikely that any of these matters would have changed the Court’s mind, had the justices been aware of them. Nor does it much matter that the Court made no mention at all of the ‘accusatorial’ nature of Australian criminal justice, a staple of its past decisions, or dwelt on how the abolition of Prasad directions would mean that more accused people will be judged (as Prasad himself was) by a jury after they have just witnessed the accused exercise his right to decline to testify.

But I do think it extraordinary that, in 2019, Australia’s apex court can rule on a trial practice that was applied to the benefit of a victim of extreme domestic violence in a homicide trial without any significant consideration of the impact of its ruling in such trials. If the Court had been interested in doing so, the key facts were all there for the justices to see.

The railing up there, then you can see concrete, that’s what you walk on, but there’s a little bit of concrete that protrudes past that fence on the outside. So when he’s done that I’ve managed to grab onto the concrete and hold on. Thank you Ms Dunlop. That completes your evidence, you can go back to the dock. Thank you.

The appeal book – the book of materials placed before the justices for their consideration – contains extracts of the trial that prompted the DPP’s request for the High Court to ban the Prasad direction. It shows how Shane Gardner pointedly told Lex Lasry that he sought a Prasad direction at the ‘instruction’ of his client. It reveals that, after the jury opted to hear more of the case, Gardner immediately told Lasry that his client ‘asked me to raise with you’ her concern about having to testify over two days rather than one given the evidence ‘involves a number of deep sensitivities’ (prompting Lasry to wave the usual trial order and let the defence present their lone expert witness first.) While the appeal book skips nearly all of Gayle Dunlop’s testimony, it includes the very last piece of evidence the jury heard before they acquitted her: Gardner asking her to mark a photograph of the flat she shared with Reid so that the jury could see exactly where she hung from a first-floor balcony after her de facto threw her over the edge.

Had any or all of the Court’s seven justices read this material, I find it hard to believe that they would have described the sole or even main benefits of the Prasad process as ‘saving of time and costs, and restoring the accused to his or her liberty’. Gayle Dunlop didn’t ask her lawyer to seek a Prasad direction to save the Supreme Court money and I think it unlikely that her concern was to end her 497 day stay in prison a day or two early. Rather, her goal was surely to avoid having to relive the horrors of life with her abusive partner on the witness stand.

Likewise, had the justices contemplated this sequence of events for more than a moment, I doubt that they would have been willing to dismiss jurors who seek to acquit early as disregarding their oaths by acting ‘without the assistance of addresses and the judge’s instruction on the applicable law.’ Rather, it is clear that the jury, having heard Dunlop’s testimony, were strongly motivated not to keep her waiting a moment longer to learn her fate. Can anyone doubt that they already knew at that stage that three more speeches from lawyers and a judge would never overcome what they had just heard from her mouth.

Speculation aside, what we know for sure is that Justice Lex Lasry saw fit to give the jury this option to do so in this particular case, despite his full awareness of the difficulties and even risks of the practice. He would surely be horrified to learn that his compassion and care for a victim of years of abuse would prompt a less careful and compassionate non-trial court to forever bar that option for future Australian judges.

But I am sure that he would have no regrets. Marking Lasry’s retirement last year, John Silvester wrote:

If you want to make Lasry cry, there is a simple way. Put on the iconic Al Pacino speech in Scent of a Woman, the final scene in Dead Poets Society or the climax of 12 Angry Men. “No matter how many times I see [them], they always get me.”

I suspect he also cried a little as he gave Dunlop’s jury his final direction:

Members of the jury, the only thing that remains for me to do now is to thank you for your service. We’ve been together now for over a week and and I’m sure you, if you didn’t already know, I’m sure you now clearly understand what an important responsibility jury service is. So on behalf of the community and in particular on behalf of the court can I thank you for your commitment to the case. It’s not been an easy case for all the reasons that are obvious, I don’t need to recount them. If I may say so, and I say this extremely rarely, in my opinion your verdict was a most appropriate verdict and brings this awful saga obviously to a conclusion.