Sampling by the sea – collecting mosquitoes in the Mornington Peninsula

Words and images: Véronique Paris

It’s 7.30 Saturday morning – what are your plans for the day? While you may be still in bed contemplating a coffee, or still sound asleep, I’m packing the PEARG ute with a stack of small buckets, strips of red felt, some rabbit food, and a 20lt jerrycan of water. I perform the usual safety checks, then head off down to the Mornington Peninsula. Weird equipment for a weekend at the beach? That’s right; I’m not off for a swim, I am tracking down mozzies.

Let’s take a step back and let me tell you what this is all about: I am in the first year of my PhD, studying disease-transmitting mosquitoes in Australia. One particular disease I am focusing on is Buruli ulcer. The disease is caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans and occurs in many countries around the world, usually in tropical areas. Recently, for reasons we do not fully understand yet, cases of Buruli ulcer have dramatically increased around the Mornington Peninsula. You can read Jason Axford’s previous blog for more background about our work on the Buruli project.

As it stands we aren’t certain what exact role mosquitos play in its transmission, though evidence to date points toward them being a culprit. Besides conducting rigorous experiments in the lab, I also want to address critical questions about the mozzies in their natural habitat. How far do these mosquitoes disperse in the area? How big are local populations? When does the peak season start? To investigate these questions (and several others), postdoctoral fellow Tom Schmidt and I laid plans to sample mosquitoes in the hot spot of Buruli ulcer cases between Portsea and Rye to collect samples.

Ever wondered what a mosquito sampling trip looks like? Probably not but here we go: The species we are interested in is Aedes notoscriptus, commonly known as the “Australian backyard mosquito” – scourge of many BBQ. It lives in close association with humans, loves some greenery and happily uses almost any available puddle of water (such as potted plants) as a breeding site.

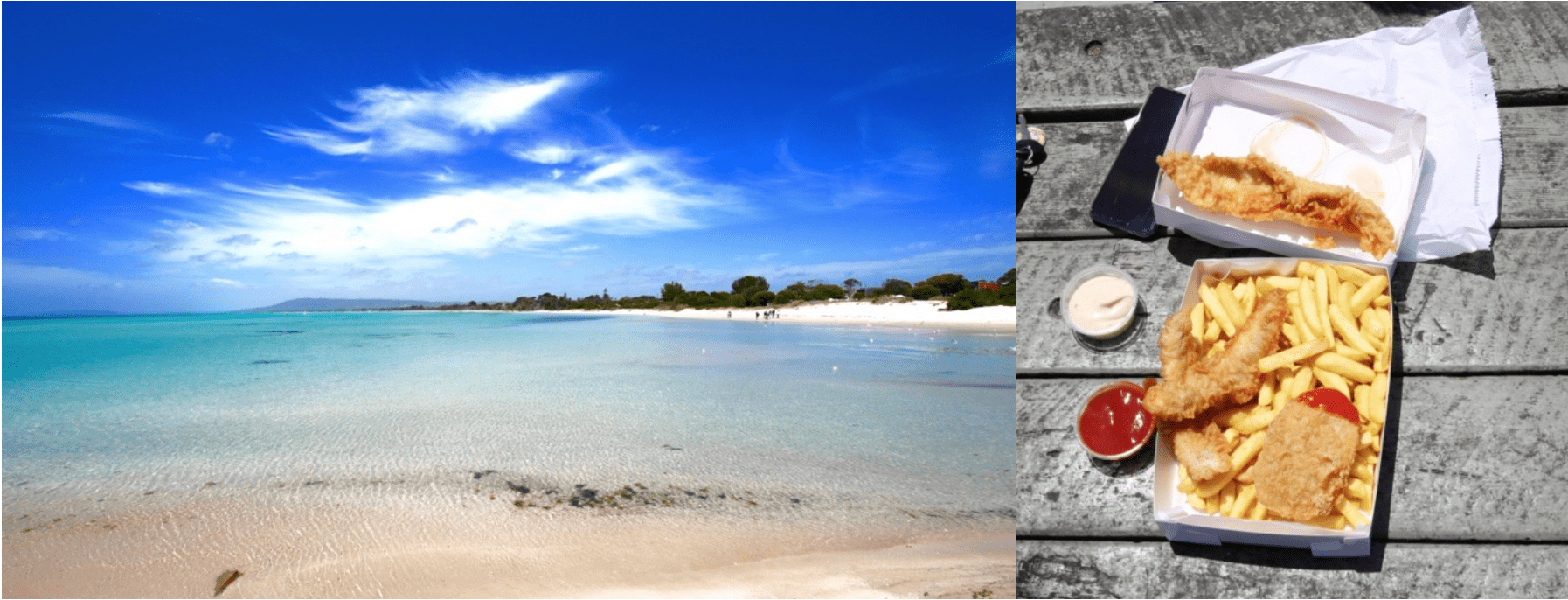

The picturesque field sites of Mornington Peninsula

Rather than hunting down the mosquitoes themselves we’re after their eggs. In order to collect eggs we set up oviposition traps aka ‘ovitraps’. These traps are simpler than you might expect: Small black buckets, filled halfway with water with a strip of red felt pegged to the rim offering a convenient place to lay their eggs on. We add a little rabbit food to convince the mozzies that the water is suitably stagnant.

The high-tech ovitrap is as simple as it is effective (and cheap!)

Tom and I spent all Saturday knocking on doors seeking permission to place traps around houses. Most residents were happy to support our research and had no issues hosting a couple of traps. If we happened to knock on your door, thank you very much for your help! Without your support this study could not be done. It was great to chat with locals about and their experiences, opinions and anecdotes regarding the Buruli ulcer epidemic.

After setting up a good number of traps across the region we made our way back into the city. A week later we headed back down to pick up the first batch of felts, swapping them out for fresh ones for another week of sampling. We found eggs in almost every location we set traps, a relief for us that our strategy was effective, though maybe not the best news for locals looking forward to enjoying the outdoors this summer.

Left: An Ovitrap after a week, these mosquitoes are quite happy with dirty stagnating water. Right: Strips of felt after being collected.

Closeup of mosquito eggs on felt.

There are definitely worse places to work on a Saturday, so we treated ourselves to a walk along the back beach to soak up the scenery.

Left: Tom and I after a long day of collecting samples. Right: The scenery we got to enjoy.

Unfortunately the work doesn’t end with collecting the eggs. Each felt needs to be dried and then submerged in water to hatch the eggs, this simulates the natural conditions that stimulate hatching. The hatchlings will be raised into adulthood before finally being prepared for molecular population genomic analyses.

Collected felts in hatching containers

Left: A recently hatched mosquito larva Right: Male and female adult Ae. notoscriptus.

I’ve just got back from the third and final Saturday sampling trip in a row. The final trip is the easiest as I just need to tip empty and stack the buckets in the ute and bag up all the felts. Again, I got lucky with fine weather and had time left to enjoy fish and chips by the beach before heading back to the lab.

Left: The beach on the bay side of Rye. Right: Well-deserved fish & chips.

So now it’s time to nurture some baby mozzies before moving towards the molecular lab, where I will prepare them for DNA sequencing. After that, I will spend many hours at my computer analysing the data and trying to shed some light on the many open questions about the Buruli ulcer epidemic. A PhD in biological science might make you get up early and work on a few weekends here and there, but it certainly never gets boring, and I very much enjoy the diversity of work involved.

Keep your eyes on this space; I will definitely share what these samples have told us further down the line.