‘Donkey Work’ and the History of Labour

Kathryn Smithies, Associate in History, recently published the book Introducing the Medieval Ass, on the cultural and socio-economic history of the donkey (previously known as the ass) in the Middle Ages and beyond. She also blogs about all things donkey at bloggingdonkeys.com. In this piece, she explores the history of the phrase “working like a donkey”, tracing the shift from animal to human labour during the Industrial Revolution.

After spending over a year reading everything I could about the donkey in the Middle Ages, I learned that many features of the medieval view on the donkey remain in place today. In both medieval and modern times, donkeys have been associated with the qualities of being stubborn, dull, dim-witted. Most of all, however, the characteristic most consistently attributed to the donkey is a capacity for hard work. Medieval writers described the donkey as well ‘suited to heavy work’ and there is no doubt that in many developing countries the donkey remains a hard-working beast of burden today.

After spending over a year reading everything I could about the donkey in the Middle Ages, I learned that many features of the medieval view on the donkey remain in place today. In both medieval and modern times, donkeys have been associated with the qualities of being stubborn, dull, dim-witted. Most of all, however, the characteristic most consistently attributed to the donkey is a capacity for hard work. Medieval writers described the donkey as well ‘suited to heavy work’ and there is no doubt that in many developing countries the donkey remains a hard-working beast of burden today.

It is this persistent relationship between hard work and donkey, and how that has been applied to human activity, that interests me the most. Terms such as “working like a donkey” and “donkey work” allude to demanding and gruelling labour; the Oxford English Dictionary describes “donkey work” as the “hard or unattractive part of an undertaking”.

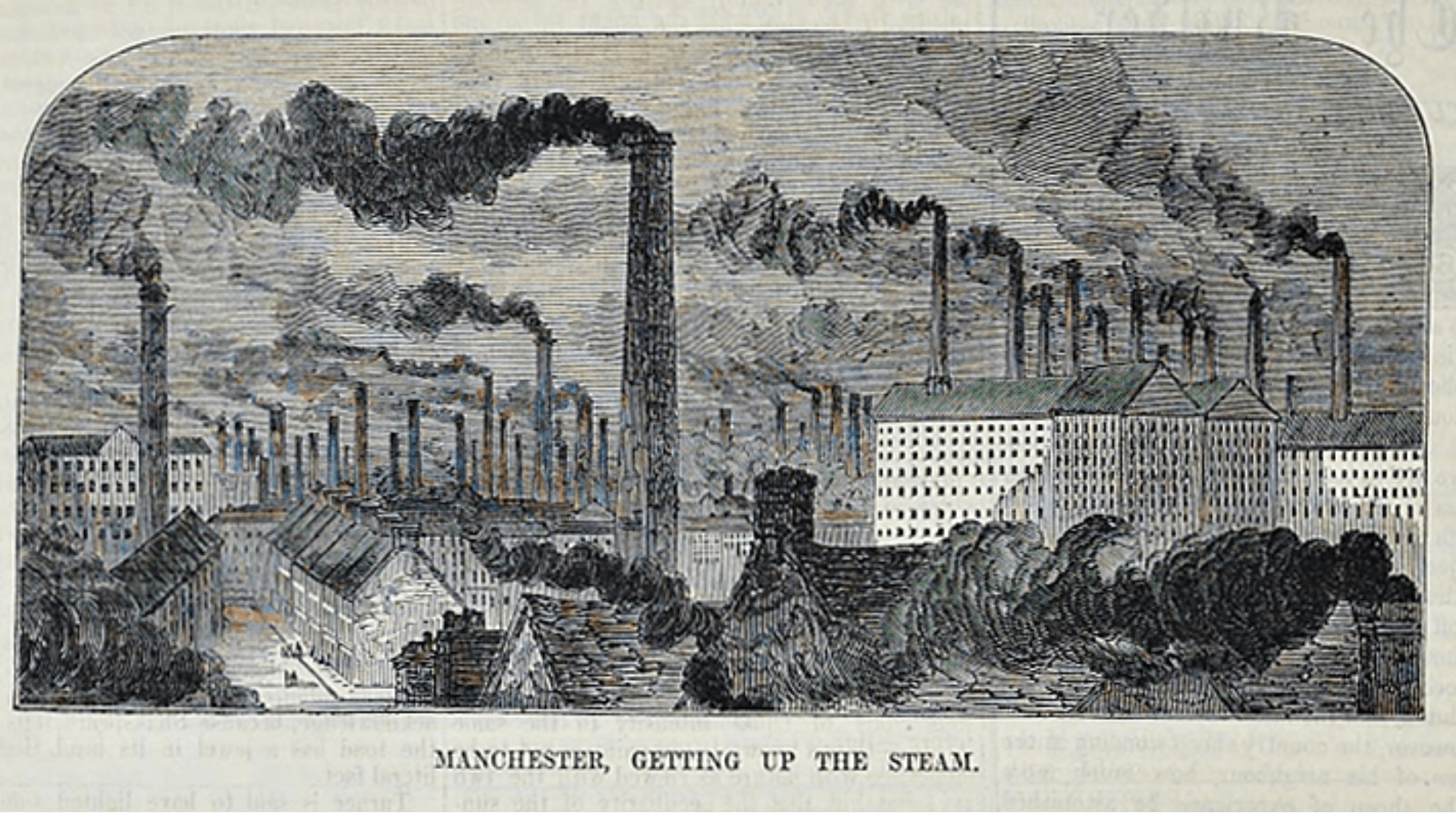

The Industrial Revolution (broadly taken as mid-eighteenth century to mid-twentieth century) stands out as a time when the exercise of hard work transferred from animal to human. This was a time when thousands of men and women migrated to towns and cities, lived cheek by jowl, and worked like donkeys in the newly emerging manufacturing industries. The north of England became the centre for textile manufacturing: predominantly cotton in Lancashire, due to its humid climate, and wool in Yorkshire. Two mid- to late eighteenth-century inventions, the spinning jenny and spinning mule, were responsible for the jump from handmade to machine-made and each had a link to the donkey. Their development led to humans working like donkeys.

Spinning Jenny

In the second half of the eighteenth century, as spinning was becoming more mechanised, it moved from a cottage industry to a large-scale manufacturing process, thanks to James Hargreaves’s invention of the spinning jenny (c1764). This machine allowed the user to operate eight spindles rather than one, meaning that the ‘spinster’ could produce eight threads in the time it had previously taken to produce one. Soon, the number of spindles that one spinster worked grew to over 100 and the large machines this required marked the end of the cottage industry. Although this machine bears the name of a female donkey, it is not actually named after a Jenny; rather, rumour has it that jenny is a Lancashire term for engine.

Although an improvement on an earlier spinning machine, the spinning jenny produced weak thread that could only be used for the weft part of cloth. Just a few years after the introduction of Hargreaves’s spinning jenny, in 1769 Richard Arkwright, an early industrialist, patented the water frame which used rollers to produce threads suitable for the warp part of the cloth. Its name – water frame – came from the fact that it used water to power the machine, but not in the actual manufacturing process.

Spinning Mule

Then, in 1779, Samuel Crompton hybridised the two processes into a machine he called the spinning mule – and, of course, the living four-legged mule is also a hybrid, being a cross between a horse and donkey.

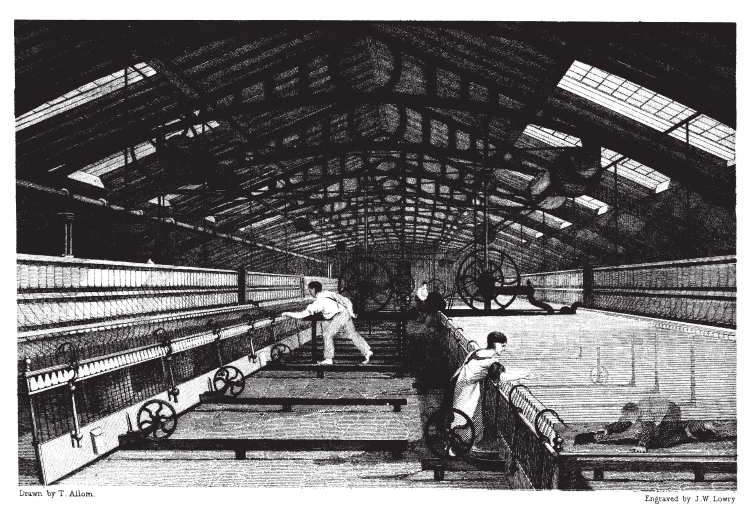

A combination of Hargreaves’s and Arkwright’s inventions, the spinning mule’s uniqueness was that it could simultaneously stretch and twist the thread which produced stronger cotton threads, which would then be woven to make cloth. Unlike the original spinning jenny that held eight spindles, the carriage of a spinning mule carried up to 1,320 spindles. Size-wise the machine could measure up to 150 feet (46 m) long and moved forward and back a distance of 5 feet (1.5 m), four times a minute. The operator, or piecer, walked with, and along, the carriage piecing together threads that broke or ended. Two young children, known as scavengers, would work with the operator sweeping and clearing dust from the undercarriage.

When it was claimed that a child piecer walked twenty miles during one working day, John Fielden, a factory reformer and advocate for the welfare of child workers, set out to check the claim. In a speech to the House of Commons (1836) he said that he had gone “into my own factory, and with a clock before me, I watched a child at work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it nothing short of twenty miles”. This would be hard work for anyone and certainly embodies the image of working like a donkey.

But it was the scavengers, who crawled on all fours to pick up the loose cotton from under the machinery whilst in perpetual motion, who personify most the hardworking subjugated beast. One young scavenger told of his constant backache from stooping and how, when he had taken the liberty to sit down, his overlooker had instructed him to “keep on his legs”. A piecer told of the toil it took on his young body, saying that “my evenings were spent in preparing for the following day – in rubbing my knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists with oil, etc. I went to bed, to cry myself to sleep, and pray that the Lord would take me to himself before morning”.

This video clip shows an authentic spinning mule in action. The moveable carriage holds over 100 spindles and moves continuously to and from the body of the machine. As it moves away, the thread is pulled through the rollers and stretched and twisted, before being wound up as the carriage returns to the body of the machine.

If you remarked on the volume of that one machine, imagine working in a factory with multiple spinning mules. John Clynes, a British Labour MP and staunch unionist, started work as a ten-year old as a ‘little piecer’. He later recalled his time in the cotton mills, commenting on the noise, “Clatter, rattle, bang, the swish of thrusting levers and the crowding of hundreds of men, women and children at their work. Long rows of huge spinning-frames, with thousands of whirling spindles”.

The Industrial Revolution transformed people’s lives. Whereas animals had previously borne the brunt of the workload, it was now transferred to machines. But machines needed people to work them and in that moment of mechanisation the burden of hard work passed from animal to human. The beast known for its ability to endure hard work lent its name to mechanical inventions and gave meaning to the human endeavour of working like a donkey.

Kathryn Smithies’ recently released book (University of Wales/University of Chicago Press) is now available in Australia. Introducing the Medieval Ass presents a lucid, accessible, and comprehensive picture of the enormous socioeconomic and cultural significance of the ass, or donkey, in the Middle Ages and beyond.

Feature image: Man loading a bag on a donkey, from Theological miscellany, including Peraldus’s Summa de vitiis, produced in England, c1236–1250. British Library, Harley MS 3244, Folio 48r