Percy Grainger performing the museum

I visited the Grainger Museum on Tuesday 21 August. As the 2018 recipient of the IMAC award, I have been keen to explore the many collections based on campus at the University of Melbourne. The only knowledge I had of Percy Grainger was that he composed that song about the English country garden, which my friends and I used to sing when we were younger in the playground. Besides this, I had no idea about the sheer extent of Grainger’s extraordinary character. I had anticipated that the museum would provide me with a showcase of important, historical objects relating to this figure in Melbourne. To describe the collection as a showcase is an understatement. I was overwhelmed by the diversity of the objects, and I couldn’t help but feel like I was in an alternative, historic version of Instagram within a museum context. It seems that Grainger was well ahead of the times; he had taken a concept and amplified it, by constructing his life in a way that only he would want it to be seen by the public eye, like his very own beautifully refined and curated Instagram account. Even now, in the days after Grainger’s death, the museum feels very true to his original intention and ethics.

So I began to collect manuscripts, musical sketches, letters, articles, mementos, portraits, photographs, etc., by and of those English-speaking Scandinavian composers that seemed to me the most gifted and progressive – always with the intention of someday putting this collection on permanent display in Melbourne. [1.]

This quote, taken from Percy Grainger’s essay outlining the aims of the Grainger Museum, has struck me as particularly appropriate towards my research into how Grainger is a considered and purposeful performer and how he also performs the museum in its own entirety (from the very conception of the idea behind a museum of himself).

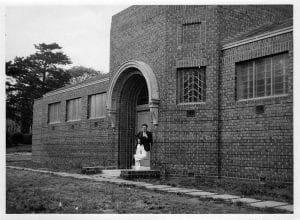

To give some context behind this extensively unique collection here at the University of Melbourne, the Grainger Museum is the only purpose-built autobiographical museum of its kind in Australia. The building was officially opened in December 1938, and it was designed in close consultation with Grainger and the University’s architect, John Gawler of the firm Gawler and Drummond. The collection comprises more than 50,000 items, relating to his musical career such as scores and manuscripts, alongside personal items ranging from all sorts of weird and wonderful objects: diaries, ethnographic objects, furniture, decorative arts, photographs, artworks, clothing, correspondences with famous and infamous contemporaries and, lastly, a dedicated shrine of objects belonging to his Mother, including a lock of her plaited hair. Consider the most bizarre object, and it is likely that Grainger collected it for exhibiting within the museum.

The death of Grainger’s Mother in 1922 instigated the planning of the Museum. In a letter to his friend, Balfour Gardiner, dated 3 May 1922 he wrote: ‘Could plot of ground (owned by me) next to White Plains home be used for building [a] small fireproof Grainger Museum?’

This sentence especially amused me.

There was another quote located in the entrance of the museum on an information panel that I discovered after looking at the collection. It amusingly read: ‘Never completely comfortable as a performer, Grainger referred to himself as a ‘tone-wright,’ a maker (or composter) of musical sounds.’

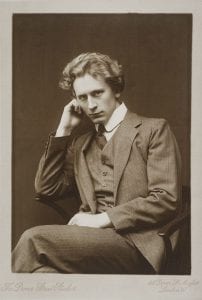

Of course, it would be wrong of me to assert this fact false, but it seems implausible that Grainger didn’t feel comfortable as a performer. This, in fact, adds to the notion of performativity within the museum. The first directed room of images of himself is a perfect example of a somewhat narcissistic face-value that we see across social media platforms all the time today. I loved the array of “selfies” dotted across the walls, even displaying pictures of past lovers amongst staged portraits of his Mother and Father. The element of performance is activated right from the start of the viewer’s journey around the museum within this gallery. He filtered out photographs presenting the best angles of himself along with other fascinating artefacts such as a fob watch and chain gifted to Grainger from Nina Greig in 1907 with a note attached reading, ‘take it, keep it, and never forget him.’ The “him” referred is the original owner of the watch, Edvard Greig, the leading Norwegian composer of the Romantic era. These associations allude to a further understanding of a fabricated self-image and the snippets of the people that played a role in Grainger’s life and their pieces amongst the images of him all contribute to his performance.

The narrative surrounding the collection resides as speculative fiction. From the controversial gossip around the “too-close-for-comfort” relationship with his Mother, to playing free music with experimental and highly imaginative instruments constructed by hand like Kangaroo Pouch Tone Tool; Percy Grainger performs himself, his objects and the museum.

Alice O’Rourke

International Museum and Collections Award recipient

Leave a Reply