Imagining a sublime hell: John Martin and Paradise Lost

I first encountered Romantic artist John Martin’s Satan viewing the ascent to Heaven in 2018, as part of the Dark Imaginings exhibition at the Noel Shaw Gallery in the Baillieu Library. It is just bigger than the size of an A4 sheet of paper in black and white, with the fine clarity afforded mezzotint prints, and shows the tiny winged Satan crouched on a cloud, a near vertical staircase behind him dotted with angels and awash in heavenly glow. The image, although small and monochromatic, is entirely, endlessly, captivating.

This print, from a series of 25 (proofs for the edition published 1825-1827) all held in the Baillieu Library Print collection, is from Martin’s 19th century vision of John Milton’s 17th century poem Paradise Lost (first published 1667). Martin was far from the first or only artist to illustrate this poem: famously William Blake and Gustav Doré illustrated the work, and the Baillieu Library’s own collection has further prints by Thomas Stothard, Francis Hayman and Henry James Richter—all from the mid 18th to 19th centuries, a near 150 years after the poem was written.

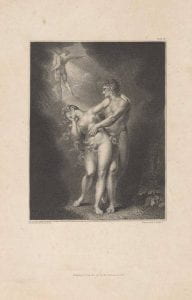

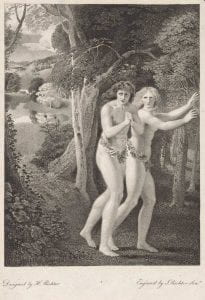

Like so many biblical themes that came before and after, artists were inspired not only by the text itself, but often one another—creating the biblical iconography we recognise today. Take for example the expulsion from the garden of Eden: a theme not unique to Milton’s poem, but all biblical iconography, and owing much to Masaccio’s 15th century fresco. Adam and Eve, now awoken to their shame and sin, are driven from Paradise side-by-side, their grief and disgrace visible on their faces as they shield their newfound nudity. The concept is clear and the image even more so: here are two people who have wronged, now unwelcome in a place they once called their own.

Martin’s take on the subject is recognisable insofar as Adam and Eve leave the garden side-by-side, newly clothed and in visible grief. Yet the couple are confined to the right-hand corner, dwarfed if not for their luminous skin, against the tempestuous, wild background. It is not the horror of their individual human reaction, but rather the fear of the darkness, the space, the cliffs and their fragility in this unflinching landscape, that arouses the fear of leaving Eden.

Mountains, caverns, water, celestial bodies and great, inconceivable space are consistent themes throughout Martin’s Paradise Lost series, and are an essential proponent to the Romantic movement of which he was a part. Romanticism, while sometimes difficult to define, was largely concerned with subjective human condition over rational truth: a nostalgia or infatuation with past, forgotten or neglected emotional experience. In the realm of aesthetics, Romanticism manifested in a tendency towards the beauty of the natural world, and importantly, the concept of the sublime. The sublime is a physical sense, which while not totally void of beauty, in many ways eclipses the simple pleasure of viewing something pretty. Natural or overwhelming themes—such as cliffs and mountains, or light and darkness—are as alluring as they are disturbing and, for 18th and 19th century fixations on the complexities of emotion, they expressed the supreme duality of human experience.

In Martin’s Paradise Lost then, we see an artist concerned less with illustrating the simple words on a page—a man and woman in grief—than an emotion. In his depiction of Pandemonium—Milton’s capital of hell—Satan stands on a rocky outcrop looking beyond an ocean of flames and soldiers to a mammoth building receding so far into the background as to disappear altogether. Contrast this to Stothard’s depiction of the council of Pandemonium, and the Romantic implications of Martin’s works become clear. Cliffs, great buildings, oceans and skies—any natural or imposing force as horrifying and dangerous to the human mind as it is attractive—had the potential to inspire a realistic sense ineffable divine creation per Paradise Lost.

Finally, then, Satan viewing the ascent to Heaven is not only captivating because of its subject and the magisterial staircase awash in divine light. The cumulative effect of light and dark, linear and nebulous movement, billowing clouds, and fine, hair-like steps creates an image as equally alluring as it is overwhelming. I invite you compound this with the fact that in order to view the little print clearly, we must peer up close and carefully decode its detailed lines. The print itself is so small, yet the image’s interior perspective on such a grand scale as to be disturbing. In this contrast of size and perspective, light and dark, intrigue and fear, the print becomes a vignette or portal into the wonderful, perilous world of Paradise Lost.

Bianca Arthur-Hull

Special Collections blogger

Categories

Very interesting and informative.