Attitudes to the Ancients

The Grand Tour of the eighteenth century offered a continental education for many aristocrats and scholars, architects and artists. Although there was no set order to the Tour, many visitors chose to arrive in northern Italy from France before making the journey down to Rome, regarded as the pinnacle of the journey for studying classical remains. They would then go to Naples, the city for buying souvenirs. The discovery of the cities buried under lava at Herculaneum in 1738 and at Pompeii in 1748 created a surge of tourists and an explosion of interest in antiquities. Visiting Vesuvius added a new and terrifying experience to the itinerary of the Grand Tour. The fragment of a larger Map of the Bay of Naples (1772) displaying a spectacular eruption juxtaposed with ancient ruins, was designed for Grand Tourists, and dedicated to William Hamilton (1731-1803).

![Antoine-Alexandre-Joseph Cardon after Giuseppe Bracci, [Fragment of] Map of the Bay of Naples, (1772), etching and engraving, Baillieu Library Print Collection, the University of Melbourne. Gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton 1959.](https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/librarycollections/files/2015/07/1959.2959-MF-300x206.jpg)

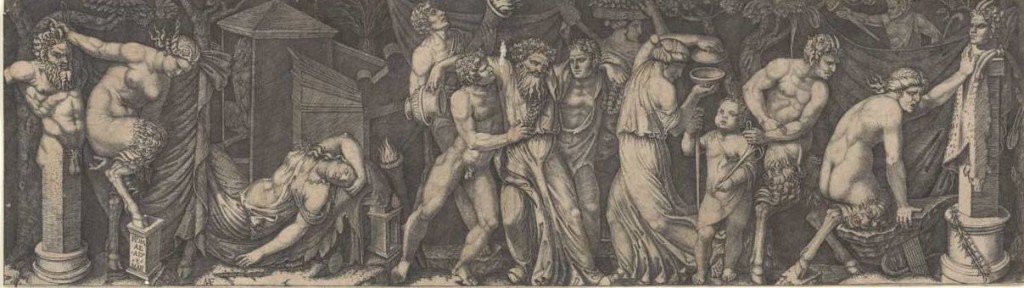

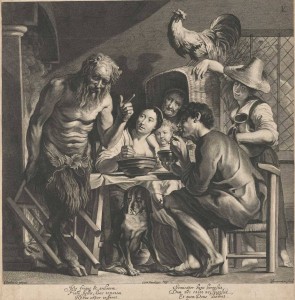

William Hamilton purchased George Romney’s painting of Emma Hart in the role of a priestess of Bacchus while he was visiting England and returned to Naples with it. The Charles Knight stipple engraving, Lady Hamilton, 1797, reproduces this portrait. Emma Hart was then the mistress of William Hamilton’s nephew, and she was effectively acquired by William Hamilton and also moved into his villa in Naples. Here she found success as a performer and hostess. She began her career as a performer posing as a goddess on a pedestal outside a Dr Graham’s medical practice in England, an inspiring specimen of health, complete with antique costume. [2] Later becoming his wife, Lady Emma Hamilton she evolved her poses into what became ‘Attitudes’ or short performance montages, where she embodied figures from the ancient world. These were staged in the Hamilton residence for Grand Tourist. Among their guests was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. In his Italian Journey, he described Emma Hamilton as the contemporary reincarnation of classical antiquity:

Sir William Hamilton…has had a Greek costume made for her which becomes her extremely. Dressed in this, she lets down her hair, and with a few shawls, gives so much variety to her poses, gestures, expressions etc., that the spectator can hardly believe his eyes. He sees what thousands of artists would have liked to express realized before him in movements and surprising transformations – standing, kneeling, sitting, reclining, serious, sad, playful, ecstatic, contrite, alluring, threatening, anxious, one pose following another without a break…In her, he has found all the antiquities, all the profiles of Sicilian coins, even the Apollo Belvedere. This much is certain: as a performance it’s like nothing you ever saw before in your life. [3]

Emma Hamilton’s attitude to the ancients was as original other artists, writers, historians and collectors of the eighteenth century who were rediscovering the wonders of antiquity during the age of the Grand Tour.

The fragment of the Map of the Bay of Naples and Lady Hamilton are on display at the Ian Potter Museum of Art as part of the exhibition Souvenirs of the Grand Tour: The Vizard Collection of Antiquities until 25 September 2015. They also feature in a new book released in August 2015: The Piranesi Effect edited by Kerrianne Stone and Gerard Vaughan, available through NewSouth Publishing.

Notes

[1] A Catalogue of the Portland Museum: lately the property of the Duchess Dowager of Portland, deceased, which will be sold by auction by Mr. Skinner and Co. on Monday the 24th of April, 1786 … in Privy-Garden, Whitehall… [London?]: Catalogues may now be had … of Mr. Skinner and Co., Aldersgate-Street, 1786

[2] Andrei Pop, ‘Sympathetic spectators: Henry Fuseli’s Nightmare and Emma Hamilton’s Attitudes’, Art History, Nov 2011, Vol. 34, Issue 5, p. 942

[3] J.W. Goethe, Italian Journey: (1786–1788) J.W. Goethe; translated by W.H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970, p. 208