Dengue-blocking bacteria endure the heat

Bushfires. Coral bleaching. Heatwaves. These disastrous events are a harsh reality in Australia. And they’re only going to become more frequent and severe with climate change. Last year, 2019, was Australia’s hottest year ever recorded, and records will continue to be broken.

Climate change will also have unprecedented effects on human health. In just one example, virus-transmitting mosquitoes will expand their range in the future as temperatures warm. And they could bring a higher incidence of dengue fever and the zika virus with them.

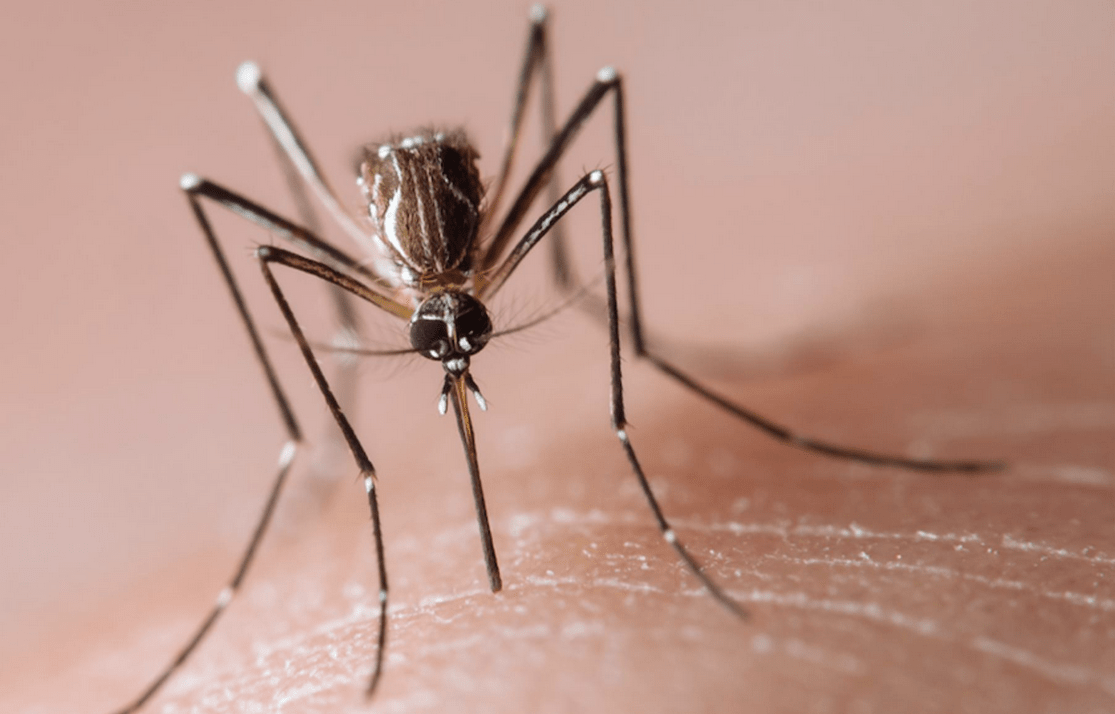

Although we can’t stop the mosquitoes from spreading, we can stop the viruses they transmit. A recent approach to dengue control, targeting Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that can spread dengue and zika, has been immensely successful following field trials. This approach uses a bacteria in mosquitoes called Wolbachia that can act to block dengue and zika.

Wolbachia live inside the cells of insects and are passed from one generation to the next through females. Wolbachia can have dramatic effects on their insect hosts, often giving the females that carry Wolbachia an advantage.

Using bacteria to control mosquitoes

Wolbachia can also turn males into females or cause sterility when males carry Wolbachia but females don’t. But importantly, some strains of Wolbachia protect their hosts against viruses.

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes don’t carry Wolbachia naturally, but the bacterium has been introduced into this species in the laboratory to make them less capable of transmitting dengue and other viruses. By releasing these mosquitoes into the wild, the bacteria can spread through mosquito populations and reduce dengue transmission.

The first field trials began in 2011 in the suburbs of Cairns in far north eastern Australia where tens of thousands of laboratory-reared mosquitoes were released over ten weeks.

Today, dengue in Far North Queensland is virtually extinct thanks to city-wide interventions, and the Wolbachia remaining at high levels in the mosquito population. Releases of mosquitoes carrying Wolbachia are now expanding to other countries.

In the Pest and Environmental Adaptation Research Group (PEARG) at the University of Melbourne, we are now looking to the future. We want to know how long Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes will remain effective, and if their beneficial effects on virus blocking will be compromised by rising temperatures from climate change.

Previous research from our laboratory has shown that Wolbachia are indeed vulnerable to high temperatures. Mosquitoes exposed to heatwave conditions in the laboratory have lower Wolbachia levels and the bacterium is no longer passed on to the next generation of mosquitoes.

Waiting for the Tiger mosquito

When we took these experiments to the field, we found the same result – mosquitoes partially or completely lost their Wolbachia unless they were raised in cooler locations in the shade.

So when in 2018 Cairns experienced its hottest day on record, reaching 43.6°C, it was an opportunity for us to actually monitor, in collaboration with James Cook University, the impact of heatwave conditions. The results have now been published in the journal PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Following the earlier interventions, Wolbachia is found in nearly 100 per cent of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Cairns, but this dropped below 90 per cent immediately after the heatwave.

The amount of Wolbachia in each mosquito also took a dip, which could reduce their ability to block dengue. But then when we went sampling a few months later, we found Wolbachia had recovered to be present again in nearly all the mosquitoes.

So how did Wolbachia endure the heatwave?

In follow-up experiments, we found that Wolbachia are more vulnerable to heatwaves during the early larval stages of the mosquito – the eggs and adults are relatively more resistant.

Mosquitoes lay their eggs in containers of water, so containers in the shade or with a large volume of water will be buffered from the heat, unlike those in the sun. There appear to have been enough of these refuges in the Cairns environment to keep Wolbachia at a high frequency even when ambient temperatures were extreme.

Blood for science: Putting the bite on mosquito viruses

Wolbachia in Far North Queensland appears then as if it is here to stay, at least in the short run. But success in other locations is not guaranteed, particularly in countries that almost always experience hot conditions. This requires a different strain that can provide protection from dengue regardless of temperature.

Not all Wolbachia were created equal. We discovered that a different strain of Wolbachia, originally from Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, is more heat-resistant than the one used in Cairns.

Mosquitoes with this Wolbachia strain have been released in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, leading to a reduction in dengue cases by 40 per cent. This strain could be used when other Wolbachia strains fail to establish, or don’t provide adequate protection from dengue.

Our research shows that heatwaves may only have temporary effects on Wolbachia, at least when it has reached a high frequency in a mosquito population. In Far North Queensland, Wolbachia will therefore likely continue to protect communities from dengue in future years, which is a good public health outcome.

Banner: Aedes aegypti mosquito/ Getty Images