Lasting Impressions: Understanding the significance of the Great Seal of England

Symbols and reminders of the British Commonwealth in modern day Australia appear not only in the form of images but also in the language we adopt. The terminology we use to define the status of our laws, what we choose to call the day this continent was colonised and the figures we decide to honour in the naming of our streets, suburbs and cities are all linguistic reflections of our nation’s apparent values.

Understanding the history of certain monarchical practices in England can help us to understand the origin of colonial perspectives that not only go unquestioned but still get largely celebrated in contemporary culture and society.

The University of Melbourne’s Rare Books collection houses many items that can assist in this kind of research that involves developing an understanding of the significance of a residual British colonial presence in Australia.

One such item is the Great Seal of England – also known as the Great Seal of the Realm – which has been used since the 11th century to signify the approval and authentication of state documents by the monarch. Originally made by pressing an engraved matrix into a wax and resin mixture, the Great Seal served as an accessible means of pictorial expression to show that an official document had been approved by the sovereign during a time when much of the population of England could not read or write.

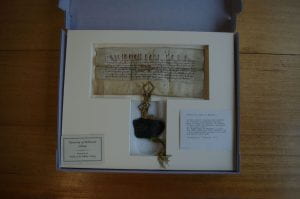

The Great Seal of England held in the Baillieu Library has only half of its original wax form remaining and is dark green-coloured, which was symbolic of documents pertaining to the elevation of individuals to the peerage – meaning to noble ranks. Blue seals would also be used but were only for documents relating to close members of the royal family and scarlet red-coloured seals indicated the appointing of bishops and approval of most other patented documents.

The document of which the remaining half of this Seal of England is attached is a letter patent (meaning a document open to the public domain) dated Westminster, 7 February 1338. It details the granting of the Hundred of Bradford in Shropshire in tail male to Henry de Ferrers. To clarify, by the approval of King Edward III, this document is granting possession of a ‘Hundred’ which was a term used to describe the administrative division below a Shire or County and ‘in tail male’ meant that the succession of the property to future heirs would be limited to de Ferrers male descendants.

In present day Australia, instead of authenticating important state documents using the Great Seal, of which there is only one unique matrix to create an impression with (now using heated thermoplastic as opposed to wax), the Governor-General acts on behalf of the sovereign to ‘assent an Act’ by signing parliamentary bills. Discussion has been raised about whether more constitutional language should be used such as assenting a ‘bill’ or ‘proposed law’ as opposed to ‘Act’ which implies that it has already become official statute law; however, to this day it remains as such.

There are significant implications in choosing to not alter this language, as it becomes the assumption that by proxy, Queen Elizabeth II has the ultimate authority to pass legislation in a country that identifies as being a representative democracy. We as a nation hold many internal contradictions – how can we be both officially a sovereign state whilst also being a constitutional democracy? How does this tension manifest and how can it be dissected and dismantled? Are we a country in which the power truly lies with the people – and shouldn’t it lie with us?

The letter patent in the Baillieu Library perhaps provides us with a prophetic image of future Australia: a nation of which the Great Seal of England has been broken.

Ana Jacobsen

Special Collections and Grainger Museum Blogger

Ana is currently studying a Master of Creative Writing, Editing and Publishing.

Categories

Hello I am the owner of an original bronze Elizabeth I Great Seal of the Realm model by Nicholas Hilliard. It is not a modern reproduction or museum replica. It was written by Robert Devereaux that Hilliard created a few copies of the seal my piece shows the Queen enthroned. I would like to send a couple of photos for you to see if I may. Respectfully, Bryan Williams.