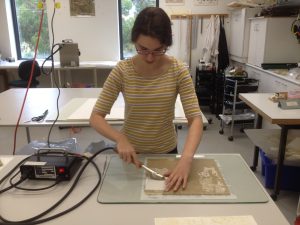

Facing The Dragon Arum

The Dragon Arum or Dracunculus vulgaris (1801), a striking mezzotint illustration, was added to the collection by Rare Books in 2017 and is currently on prominent display in Dark imaginings: tales of gothic wonder. Also on display is a facsimile edition Robert Thornton’s book, Temple of Flora (1799) where this menacing lily originates.

When the botanist Carl Linnaeus developed a system of taxonomy and began to discuss plants in terms of their sexuality, then nature became animated and the academy became enlightened. These ideas are rapturously embodied through Thornton’s book, which lavishly illustrates this new, romantic nature.

The Dragon Arum is a dangerous bloom designed to lure insects into its maw of death. As a mezzotint, it layers the versatility of the medium through the introduction of colour, and by placing the specimen before a heaving backdrop from the natural world.