Glyphs, cyphers and symbols: Mysteries by Romeyn de Hooghe

It is always satisfying to finally identify works of art in the collection that have otherwise remained cloaked in mystery. Such is the case with a group of 20 etchings and engravings in the Baillieu Library Print Collection, which remained unidentified for decades, until now.

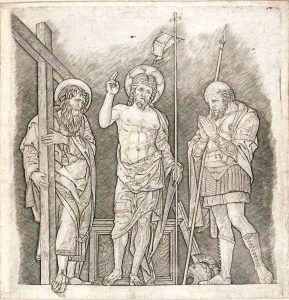

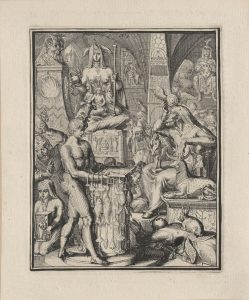

A previous researcher was convinced that these perplexing scenes were Spanish emblems, but in truth, separated from any signatures or other explanatory text, it is possible for a viewer to probe these images for hours and remain baffled as to their correct origin and meaning. This is largely because they are the product of the labyrinthine mind of Dutch artist Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708) and their true source is his Hieroglyphica of Merkbeelden der oude Volkeren (Symbols of ancient people), published in 1735.

The structure of his book is unusual; instead of a narrative it presents illustrations with a key, accompanied by copious text, to explain their content. In de Hooghe’s lifetime, the deciphering of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs had not been achieved. Thus, they invited interpretation and additionally, it was common practice in the Dutch Republic to present a symbol and apply layers of potential meaning to it. [1.] De Hooghe provides us in his illustrations symbol upon symbol and consequently an overwhelming schema of knowledge. For example, in plate three he conveys the overall theme of Iconology and the symbols represented are: A: The progress of science B: Harpocrates, the silent student C: A priest D: An archaeological obelisk E: Godly exorcism F: A statue of Hecate G: Statue of the Egyptian Horus H: Artificial austerity I: Supplicate the oracle K: Presenting the sacrifice L: Statue of Mophta. [2.]

The ancient Egyptians were not the only subject of his interpretations though, he also reasoned about the occult, science, classical mythology and religions. Although he may have begun the project with the intention to produce a history of ancient symbols, his focus on religion is such, that the production may be considered rather as a genealogy of religion. [3.] The study of Hieroglyphica is complex, yet highly rewarding experience.

Kerrianne Stone (Curator, Prints)

References

[1.] For further explanation of Hieroglyphica see Joke Spaans, ‘Art, science and religion in Romeyn de Hooghe’s “Hieroglyphica”’ in Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) (Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art), Vol. 61, pp. 281-307, 2011

[2.] Romeyn de Hooghe: Hieroglyphica — Symbols of Ancient People

[3.] Joke Spaans, p. 294