Narrating Photography

Alice Helme

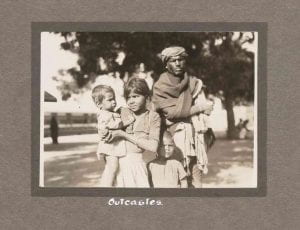

A picture says a thousand words. We all know that ubiquitous and often overused phrase. It is the cornerstone of art analysis and an art historical approach to dissecting pictorial representations. An image presents a visual narrative, conveying a story or meaning through the silent channels of sight. These narratives are fabled to tell a truth, an unaltered vision of the artists’ projected thoughts, or convey a reality of time and place. Photographs have always been revered as a mode of truth telling, as opposed to paintings and other figurative art forms that are imagined from the mind of the artist. Their image captures a moment, and in that scene of suspended time the photographer presents exactly what they saw. We are presented with the perspective of the photographer, or their directed framing of a scene. The image speaks for itself, to use another popular idiom. But what happens when alongside the photograph or series of photographs there are captions and a specific order, all of which were placed and curated by the photographer themselves? Does the meaning alter? And if so, does it reveal a kind of commentary by the photographer? Is this added information then lost in the processes of digitisation and online viewing?