The Overland Letter

Nathaniel Cutter

James Graham’s Overland Letter provides a vivid account of the early settlement of Victoria and of the hopefulness of many of its settlers, and through the physical writing style a vibrant material record of the challenges and ingenuity the colonial experience afforded. The letter was presented to the University of Melbourne Archives in 1961, within the extensive business and personal archive of Graham’s prominent trading and retail firm Graham Brothers and Co. The collection, which spans the period 1839-1960, can be found at the accession number 1961.0014; the Overland Letter and transcript at 1961.0014.00045–46.

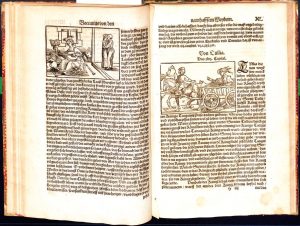

Even though James writes the diagonals in red ink to aid readability, having a transcript is extremely helpful to the modern reader! Other writers of the time experimented with different paper-saving methods, including shorthand, reusing paper, or writing over newsprint.[3] Unlike many long letters of the time, Graham appears to predominantly written in one sitting, rather than over a period of repeated folding, storage, unfolding, and additions.In July 1839, James Graham, a new settler in the Port Phillip District of the Colony of New South Wales, wrote to his family in Fife, Scotland. This letter was his first in over a year, meaning he had plenty to say, to update (and reassure!) his readers.[1] James employs a wonderful example of the prevalent contemporary cross-writing technique: writing horizontally, vertically and diagonally to save expensive paper, and filling two large leaves of heavy paper with enough text to require 40 pages of transcription – yet even still he found himself forced “to draw to a conclusion for want of paper, tho’ I have a great deal more to say.”[2]

James first recounts his five-week journey by horse and cart from Sydney through trackless bush, with only damper, tea and salt beef for sustenance.[4] Graham’s party battled thick ice, rough-sleeping, water shortages, wandering horses, falling branches, backward seasons, unusual wildlife, and bushfires, all challenges alien to his own experience and no doubt thrilling to his family in Scotland; yet at the end he wrote, “altogether I was very much delighted with the journey, and would willingly undertake another”![5]

From here James compares his new home in Melbourne, “a most astounding place”, with Sydney. The Melburnian countryside was “as Heaven to us,” but “there is not a more…beautiful harbour in the known world” than that which bisects Sydney’s “extensive and beautiful town.”[6]

Outside the cities, however, a war rages between Indigenous Australians and the newly arrived pastoralists, where the former one is reputed to practice cannibalism, “treachery and ill-will”; while the latter includes Britain’s “most debased and vilest dregs”, who “never look upon the Blacks [as] human beings, but, would just as soon shoot them…or hunt them [as a] kangaroo,” start the majority of violence.[7]

James presents a palpable sympathy for those Indigenous people who “retaliate on the oppressors,” imagining the “heart-rending” experience of being driven from “their dominions…the wild animals [killed]…[and] their women carried off.”[8]

James’ own affairs were promising: sponsored as a Melbourne wool buyer, and placed in charge of 100 acres, he lives in a log cabin until his house is built, and has learned to cook, clean and bake for himself, fancying himself “a great adept” in cookery and having “Scotch acquaintances come miles in the mornings to get a plate full of porridge.”[9] His twelve workmen live onsite with their families, and though in Australia “money is the great idol, and for it they will…undergo any hardship”, these men are “worth their weight in gold.”[10]

Port Phillip is booming, with land speculation and cattle stations proliferating and skilled jobs ready for the taking; but prices are high since everything is shipped from Sydney or Tasmania.[11] With a great sense of optimism about the new colony, James regards emigration to Victoria as an unqualified success, for: “Were I at home and know as much as I do about this country with its privations, hardships and pleasures, I should not have the least hesitation in making up my mind to come out at once.”[12] The Overland letter is an unusual artifact but it is also an ode to the complex affective responses one of Victoria’s early settlers felt towards both the land and its peoples.

Nathaniel Cutter is a current PhD student in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne, researching the experiences of English expatriates in seventeenth-century North Africa.

Citations

[1] Overland Letter transcript, 1.

[2] Overland Letter transcript, 39-40.

[3] David Livingstone famously employed this technique: https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn19119-dear-diary-i-am-sick-to-death-david-livingstone/.

[4] Overland Letter transcript, 2-6.

[5] Overland Letter transcript, 6-11, 16-17, 36-37.

[6] Overland Letter transcript, 12.

[7] Overland Letter transcript, 13-14.

[8] Overland Letter transcript, 15.

[9] Overland Letter transcript, 17-25.

[10] Overland Letter transcript, 25.

[11] Overland Letter transcript, 30-33.

[12] Overland Letter transcript, 34.