Fritz Duras: Australian ‘father’ of physical education and sports medicine

Katrina Dean, University Archivist

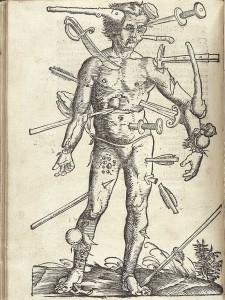

Fritz Duras’ pipe was recently transferred to the Archives along with his elegant signature block, a 1943 Workers Educational Association talk ‘Quotations for Students’, a 1944 tutorial lecture on the benefits of swimming, and some of his lecture slides on ‘human growth’ outlining the conception and growth of the human embryo. http://ow.ly/SBcUe This joins earlier deposits of his articles, notebooks, talks and teaching material http://ow.ly/SBcWl; http://ow.ly/SBd2h

Duras was the first director of physical education at the University of Melbourne to be appointed in 1937. Born in Bonn in 1896, Duras following his education at the Royal Gymnasium, served in the German infantry in World War One and was awarded the Iron Cross. He studied medicine at the University of Freiburg-im-Breisgau, worked as a house physician in the University hospital and a clinical assistant at the Association for Sports Medicine becoming director and senior physician (1929-1933). Under the Nazi laws for the reform of the civil service, which saw the dismissal of some 2000 academics across universities and research institutes, Duras was forced to resign his position in 1933 because his father was Jewish.

Quaker contacts arranged for Duras and his wife to travel to London to improve his English where he was introduced to the Academic Assistance Council who helped Jewish refugees. The University of Melbourne was planning to introduce a one year course to train physical education teachers and obtained a grant from the Carnegie Foundation of New York to employ Duras. He became the ‘father’ of physical education and sports medicine in Australia. Duras directed the World Congress of Physical Education in Melbourne in 1956 before the Olympic Games and helped realise the Beaurepaire Centre for sport and physical education built in the University in the same year. The Melbourne School of Graduate Education and the Australian Council for Health, Physical Education and Recreation have named Lectures in his honour.

The pipe is a sign of its times. The first medical reports linking smoking to lung disease appeared during the 1920s but it wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that major studies confirmed tobacco as the cause of serious diseases. Elsewhere in the Archives (1986.0107,) it was immunologist and Nobel Laureate Frank Macfarlane Burnet who took up the campaign against smoking from the late 1970s (http://ow.ly/SBe7K Series 6, Item 30), having quit himself in the 1950s.