Strange Scenes Identified in the Baillieu Library Print Collection

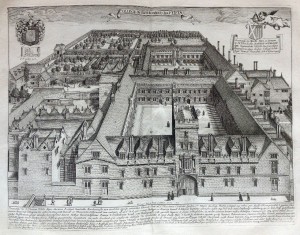

‘Unidentified. Series of twenty seven engravings from a book/ copper engravings – Dutch – ? 1650-1700 good impressions.’ This is what Dr Orde Poynton wrote in his registration book in 1960 for his print collection about a group of illustrations that subsequently remained a mystery. The key to unlocking the identity of the images lies in their peculiar subject matter. One of the most startling of the illustrations shows a scene of men attaching tapers to foxes’ tails and setting them on fire in order to burn a wheat field. What has this to do with other pictures in the series such as a man with his tongue stuck to the handle of a water pump?

Orde Poynton 1959.

University of Melbourne. Gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton 1959.

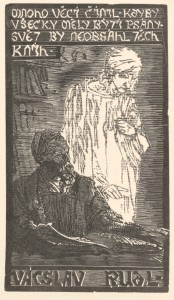

Once the scenes were recognised as emblems, identification of their source revealed they were some of the 51 illustrations from Johannes de Brune’s Emblemata of Zinne-werck first published in 1624.[1] Emblems exist throughout art history, but as a genre they appeared in the 16th-century and seem to have fallen out of usage during the 19th-century. The earliest or most influential emblem book is Andrea Alciato’s Emblemata (1531). A copy of this popular book was donated to the university library in 1903 as part of the George McArthur Bequest. Unfortunately, the library does not hold a copy of de Brune’s work on emblems.

An emblem comprises three components, including a title or motto which sits above the image and a verse or epigram which sits below. Typically their design conveyed inculcating wisdom to their audience. They have been described as word-eye pictures as the two elements are required to interpret their riddle-like qualities. Yet their meaning can often remain elusive, and in the case of the Baillieu’s engravings, without the words, they have the unintentional effect of not making any sense. Indeed, de Brune wrote in the dedication to his book that without the explanatory text, the images would be as helpless as oysters without shells.[2] Emblems are similar to fable stories and their subjects can range from scenes of everyday life through to the fantastic; a guiding hand can reach out of the sky to direct the action, or an enchanted animal can be a protagonist.

In an example from Alciato’s Emblemata, a translation from the Latin motto is: ‘Intelligence matters, not beauty’ and the prose below the image describes:

A fox, entering the store-room of a theatrical producer, found an actor’s mask, skilfully shaped, so finely fashioned that the spirit alone was missing, in all else it seemed alive. Taking it up, the fox addressed it – What a head is this, but it has no brain![3]

The illustrations in de Brune’s Emblemata are after drawings by Adriaen van de Venne, a leading emblem artist. As a text prepared during the Dutch Protestant Reformation, many of the images convey religious analogies through scenes of contemporary life. In one of the emblems the text explains God and the Devil’s battle for the soul, which is represented by two hands in the clouds finger-wrestling a pretzel.

Orde Poynton 1959.

While other images have caught the attention of scholars for their social history such as the depiction of the medical practice of leeching in one image, and Dutch manufacture of early telescopes in another. The illustration with the foxes refers to the biblical story of Samson torching the fields of the Philistines.[4] Although all of the translations are yet to be found, and the relative wisdom, or lack thereof, to setting foxes’ tails on fire and licking handles cannot be fully defined, it has been important to provide these images with some much needed context.

Kerrianne Stone (Special Collections Curatorial Assistant (Prints))

[1] For a more detailed description of the book see Marleen van der Weij, “‘A Good Man, Burgher and Christian’: the intended reader in Johan de Brune’s Emblemata,’ in Alison Adams, Marleen van der Weij, Emblems of the Low Countries: Book Historical Perspective (Glasgow: Glasgow Emblem Studies, 2003), pp. 111-128.

[2] Els Stronks, Negotiating Differences: Word, Image and Religion in the Dutch Republic (Leiden: Brill, 2011), p. 77.

[3] Emblemata: Lyons, 1550 Andrea Alciato; translated and annotated by Betty I. Knott; with an introduction by John Manning (Aldershot, Hants., England: Scolar Press, 1996), p. 203.

[4] P.J. Meertens, introduction to Emblemata of zinne-werck (Soest, Germany: Davaco, 1970), p. 4.