Connecting collections at Manchester and Melbourne

An exciting project afoot is a collaboration between the universities of Melbourne and Manchester to connect these two geographically distant, culturally rich collections. Face-to-face encounters have already taken place between scholars and special collections staff through two workshops: Manchester in July 2017 and Melbourne in April 2018. These workshops saw specialists come together and exchange ideas about the endlessly interesting works of art, books, textiles, maps and objects located in these cities.

The collections are currently being brought together in a virtual space through the ongoing development of a new Connecting Collections website. The site explores the collective’s first major research theme of ‘Foreign Bodies.’ Every month a different collection object is featured, and this month it is the engraving by Francesco Villamena, Blind man with remedy for corns (Cieco da rimedis per i calli) (1597-1601) from the Baillieu Library’s Print Collection.

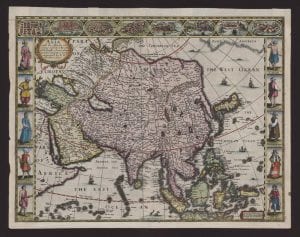

Visitors to the site may also read about previously featured items, such as John Speed’s map of Asia (1627) from the Library’s Map Collection.