Fraser’s Political Football

Adam Eldridge-Imamura

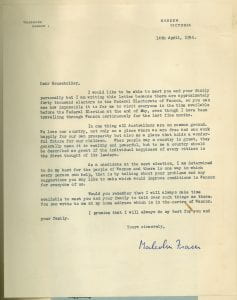

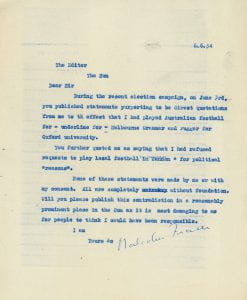

In a draft letter dated 6 June 1954 to the Melbourne newspaper The Sun News Pictorial, Fraser disputes an article that was published on its front page on 3 June 1954 that he did not play local football for “political reasons”. Continue reading “Fraser’s Political Football”