Revolutionary theatre is a risk worth taking

Looking back at La Mamas’ 50-year history, from inception in 1967 when Betty Burstall created an ‘immediate’ theatre space in Melbourne inspired by New York’s La Mama Experimental Theatre Club, reveals not only the rise of an Australian theatre nurtured by local talent, but a larger portrait of Australian society and culture. As challenges to cultural and social norms reverberated around the globe, alternative voices in the arts were becoming a powerful form of political and social engagement. Burstall was confident that, just like in New York, Melbourne performers and audiences wanted and needed a place for avant-garde theatre, progressive music, poetry and screenings of alternative film. She wanted audiences to feel that every time they descended the stairs to the stage, that it was “a risk worth taking”.[1]

In a company newsletter from October 1969 this vision was expanded: La Mama would be a theatre to make possible “a new audience-actor relationship. It was informal, direct, immediate. It was also a playwrights’ theatre…where you could hear what people now were thinking and feeling”.[2] With a policy to present new Australian work, the move was financially risky in an arts scene dominated by the mainstream canon of mainly American and English work. “Revolutionary things are happening in theatre today and I want them here”.[3] Burstall’s ambitions for La Mama were grand, but almost immediately the revolution began, namely in the form of pushing the boundaries of the Summary Offenses Act 1966.

The earliest offender was the 1968 production of Alex Buzo’s Norm and Ahmed. The final line of dialogue “fucking boongs” is delivered by Norm to Ahmed, a Pakistani student, and saw actor Lindsey Smith arrested for using obscene language, and the play’s producer Graeme Blundell charged with aiding and abetting Smith.[4] Some five decades on and the play is perhaps even more relevant because of the offensive racial slur.

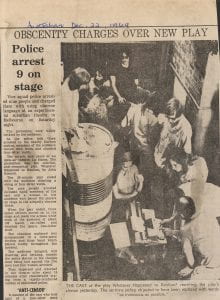

A year later, John Romeril’s Whatever Happened to Realism resulted in the conviction of nine actors for using obscene language in a public place. After a private viewing of the play, magistrate H. Bennet conceded that they were sincere in their protest against censorship, “The play, as far as I can follow, intends to show that actors and playwrights are restricted in portraying life by censorship, because of words deemed to be offensive or obscene. However, the play can be enacted just as forcibly without the singing or use of the words in question”.[5] The audience expressed their disagreement with the magistrate, following the arrested to the police station, chanting the offensive four letter word, amongst others.

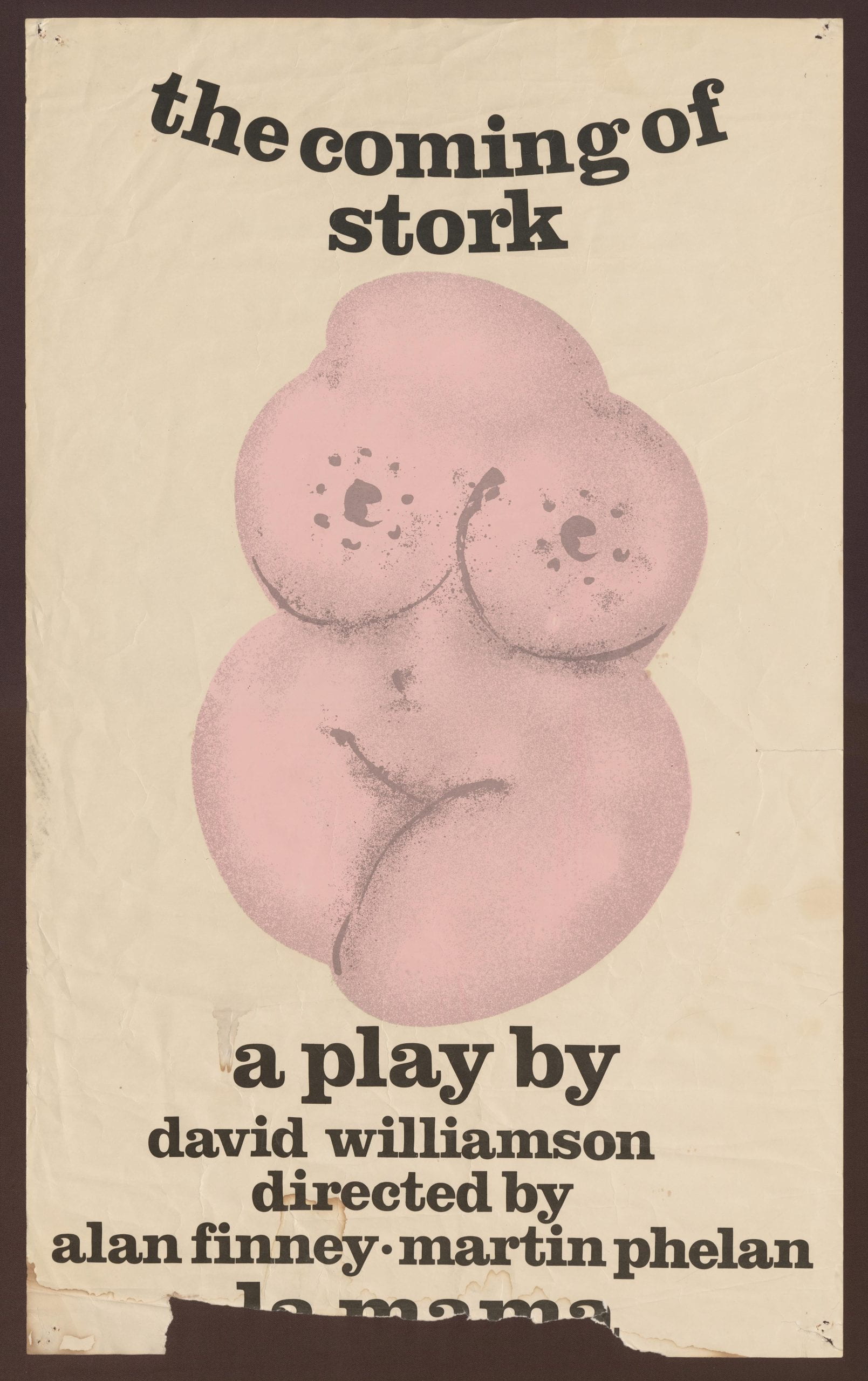

Still, La Mama continued supporting Australian writers, actors and directors, providing a place where collaboration was centre-stage. Stalwarts of the Australian theatre scene like Jack Hibberd, David Williamson and Graeme Blundell, were given the chance to practice and develop their craft, as were other performance artists, such as filmmakers Corinne and Arthur Cantrill.

In the decades following the ‘obscenity trials’, La Mama continued pushing audiences, exploring concepts of identity, and elevating voices of the silenced. Playwrights such as Mammad Aidani and Tes Lyssiotis used this platform to chronicle the variety of the migrant experience, whilst in 1990, Aboriginal actor comedian Gnarnayarrahe Immurry Waitairie and director Ray Mooney explored the relationship between black and white Australian cultures in their play Pundulumura: Two Trees Together.

The onstage events however are only part of what the La Mama archive preserves. Over 100 boxes of material spanning 1967-2006 was listed during a three-year project with volunteers from La Mama, culminating in detailed lists of records available via the University of Melbourne Archive’s online catalogue. These records represent the important narrative of women in leadership roles in the arts, Liz Jones took over as artistic director in 1977, and the story of a business not obsessed with profit survived, and thrived, for 50 years.

Local issues such as the inner-city property market boom forcing the 2008 Save La Mama Campaign, the relentless struggle to find funding, and formal recognition as a place of significant Victorian heritage, are played out through business and administrative records. A collection of theatre posters illustrates trends in art and printing, featuring lino cuts by Tim Burstall amongst a wild variety of style and quality, some still with holes left by the staples used to distribute them on light poles.

The archive also sheds light on the suburb of Carlton and La Mama’s historic role as a place for its diverse residents to express themselves. Migrant Greek and Italian communities found a home for weekly music and poetry gatherings and Burstall and Jones gave neighbouring student populations a forum to experiment with new ideas.

From the first donation of records in 1977, UMA has seen its relationship with La Mama as a valuable one, not only for volunteer projects and exhibitions but in maintaining a comprehensive record of Melbourne’s theatre history. The La Mama archive complements that of the Union Theatre Repertory Company which evolved into Melbourne Theatre Company, as well as smaller collections of ephemera from the late 19th century to the 1960s.

A selection of records and production posters from the La Mama archive is currently displayed on the ground floor of Arts West at the University of Melbourne.

[1] Liz Jones; with Betty Burstall and Helen Garner, La Mama: the story of a theatre (Fitzroy: McPhee Gribble, 1988), 2.

[2] La Mama newsletter, October 1969, La Mama Collection, University of Melbourne Archives, 1977.0109, Unit 1, Item 1

[3] Handwritten notes by Liz Jones for “La Mama: the story of a theatre”, 1988, La Mama Collection, University of Melbourne Archives, 1998.0110, Unit 19, Item 110.

[4] “Magistrate goes to see play”, The Australian, 24 July 1969, La Mama Collection, University of Melbourne Archives, 1977.0109, Unit 3, Item 19.

[5] “Actors were obscene, but sincere says SM” The Australian, 3 December 1969, La Mama Collection, University of Melbourne Archives, 1977.0109, Unit 3, Item 19.