“A library is a pleasure dome…”: Germaine Greer and libraries

Sarah Brown – Archivist, Germaine Greer Archive

“Libraries are reservoirs of strength, grace and wit, reminders of order, calm and continuity, lakes of mental energy, neither warm nor cold, light nor dark. The pleasure they give is steady, unorgastic, reliable, deep and long-lasting. In any library in the world I am at home, unselfconscious, still and absorbed.” [1]

Germaine Greer’s sublime quote from Daddy, We Hardly Knew You, her intensely personal book on her search for the truth about her enigmatic father, epitomises Greer’s sustained and enriching relationship with libraries. Libraries are Greer’s safe place, source of intellectual sustenance and demonstrably essential to her scholarship and writing.

Daddy, We Hardly Knew You is Greer‘s story of embarking in the 1980s on a search for her father’s true history, primarily through genealogical research in libraries and archives, beginning in Reg Greer’s home state of Tasmania, progressing to Victoria and ranging worldwide. As an experienced and skilled researcher, Greer makes some biting, often hilarious, observations in this book, and in associated research notebooks and correspondence held in the Greer Archive, about her impressions of the research institutions she encounters. She writes of her frustration at not being allowed to personally search records in the Tasmanian Registrar-General’s Department and Public Records Office Victoria, as she was used to at the UK Public Records Office, but having to rely on intermediaries, and to add insult to injury, pay for their services She is also shocked to find the State Library of Victoria (SLV) no longer the silent scholarly “Valhalla” she recalled from her childhood when her “dream was to live in this heavenly building and know all its secrets” but like walking into “deafening, smelly chaos” [2], as the SLV transitioned to the better resourced institution we know today, and where, despite her initial impressions, she receives useful advice from knowledgeable staff of the LaTrobe Manuscripts Library. Greer’s quote on the pleasure of libraries has in fact been incorporated in the State Library of Victoria redeveloped domed reading room, and her index cards for Daddy, We Hardly Knew You are held in the collection.[3]

Towards the end of her book, Greer gratefully acknowledges the role of archivists and librarians in finally solving the riddle of her father’s birth through their assiduous research and lateral thinking. “We were closing in on our quarry. Surrounded by gifted and hard working women the lazy man didn’t have a chance. Between my new friends, Mrs Nichols and Mrs Eldershaw at the Archives Office [Tasmania], and Mrs Rosemann at the Local History Room and Miss Record of Launceston College, and his doggedest of daughters, Reg Greer was about to be flushed from his cover. His bluff was about to be called.”[4] And their combined discovery is fascinating.

As one of the archivists cataloguing the Germaine Greer Archive, I have found evidence throughout of how much libraries matter to Greer. Series 2014.0045 Major Works shows their importance as she researched and wrote her major published works. This series contains many of Greer’s research notebooks, including several containing delightful sketches, notes and library citations, written as she traversed Europe seeking out forgotten women artists for her second major work, The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work (1979). Greer created sequences of handwritten index cards, taxonomies of reference lists, and folders of research material, often copied from library sources, for each of her major published works. [5]

Greer has an enviable capacity to work anywhere, but libraries are her essential resource, and also her comfort zone. In an article for The Guardian, Greer, reflecting on the boredom of the bookless house of her childhood and her discovery of the joy of libraries, nominated her favourite word: “…if there were a word that remains lovable to me…it would be ‘library’. ‘Tea and buns’ may be nice, but ‘tea and buns in the library’ is rhapsodic.”[6] Greer has studied, researched and written in libraries throughout her career. In 2008, she declined an invitation to appear on an English Television Book Show, ‘The Write Place’, featuring authors’ studies/places of work, replying, “I’m afraid I don’t have a study, nor do I always work in the same place. Most of the work for Shakespeare’s Wife (2008) was done in libraries…”[7]

Series 2017.0004 Correspondence with Libraries provides a detailed snapshot of Greer’s continuous engagement with libraries and archives and her reliance on these institutions and their collections to support her scholarship and research for over 50 years. This series contains her interactions with over 40 institutions, large and small, public and private, British and international, arranged alphabetically, from the Augustan Reprint Society to Yorkshire Archive Service. The files include the fine detail of her scholarly use of libraries, including borrowing slips, index cards, user guides, library pamphlets, newsletters and brochures, and, always, correspondence between Greer and the institutions on ensuring she correctly cites, acknowledges, and obtains permissions for reproduction of their collection material in her publications. Greer’s fondness for libraries is perhaps best illustrated by her retention of her library and readers’ cards, dating back to 1966. Greer’s correspondence, and daily schedules, conscientiously prepared by her personal assistants, often show her preferring to eschew offers of dinners and hospitality to squeeze library research visits into her busy speaking schedules, for example visiting the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, before returning to England after speaking at the Chicago Humanities Festival in 1999.[8]

The series also contains records of Greer’s engagement in policy, campaigns and issues relating to the development and sustainability of libraries, inevitability touching on the changing roles and capacities of institutions over the years. Greer shows herself an early adopter of some technological developments, such as her support for the development of online databases such as the Perdita Project, a database enabling remote access to early modern women’s manuscripts, and her advocacy of microfilming of rare items for preservation.

Greer is also highly cognisant of the importance of unique physical collections and the research role of libraries and their staff, no doubt understanding that many of her very specialised research interests will never be candidates for digitisation, and also seeming to relish the thrill of the scholar’s chase to track down the elusive manuscript or reference, only achieved by academic knowledge and diligent research, where she leaves no stone unturned. In 1995, her research on the short lived 17th century poet Anne Wharton (1659-1685) led her via the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, London, to Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire, where she approached the Duke of Rutland asking to see letters held in the private family archive. In her request, Greer wrote “There is so little of a personal nature that relates to Anne Wharton that I cannot bear to think we have not examined this source properly” and hoped the letters between connections of Anne Wharton would correct Wharton’s misrepresentation in history “as a pious, rich, elderly woman when she was a young libertine…” [9]

Greer has long been an advocate for libraries in both formal and informal ways. She has been on the committee of the London Library, a Friend of the Lambeth Palace Library, and a Trustee of Chawton House Library and Study Centre, “a Library for the study of the works of early English women writers (1600-1830)” which opened in 2003. She has provided tangible support by speaking at fund raising events and offering donations of her five books on early women poets, published by her self funded imprint, Stump Cross Books: The Uncollected Verse of Aphra Behn; The Collected Works of Katherine Philips: The Matchless Orinda (Vols.1-111); The Surviving Works of Anne Wharton. Correspondence also shows Greer has a finely tuned ear for the competitive rare book and manuscripts auction scene, writing, for example, of the Bodleian being outbid for a coveted Anne Wharton manuscript at a Sotheby’s sale in 2004, by the better funded Beineke Library at Yale.[10] And she has maintained an almost visceral hatred for the greedy opportunists in the book trade who make money by defacing antiquarian books by removing single plates to sell.

It would probably be easier to note libraries Greer has not used than ones she has, as her research interests have led her to access diverse libraries and collecting institutions everywhere. She has had extended relationships with certain libraries, including the libraries of the institutions she has been attached to, the University of Cambridge and University of Warwick. The University of Cambridge Library she nominates as her “second favourite library”, after the British Library,[11] and she has advocated for better resourcing for Warwick.[12]

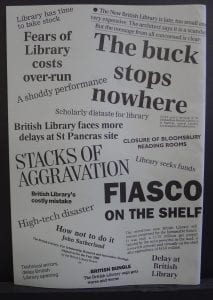

Greer’s relationship with the British Library, her “library of libraries”, is longstanding and has had complex periods, at times setting her at odds with British Library staff and the wider library profession. Greer was involved with the British Library Regular Readers’ Group (RRG) in the 1990s. This lobby group produced a series of reports, including The Great British Library Disaster (1993/1994), critical of the prolonged redevelopment, cost blow outs, and loss of the Round Reading Room at Bloomsbury with the proposed move to the new British Library building at St. Pancras. Greer took an active interest in reviews of the British Library and the move and was publicly critical of the management of the British Library and its service to its readers in this period. In a 1994 article written for The Guardian, she decried what she saw as an increasing loss of readers’ rights and inadequate care of the books in the British Library’s care[13] and Greer’s script for a programme made for BBC2 TV in the same year, went so far as to claim “For librarians readers are raiders”; that “the librarians hate being in the library as much as the readers love it”, and concluding that the books awaited liberation by the readers “from “their book prisons and the dream battle that is waged between them and their jailers.” [14] The protracted redevelopment of the British Library at St Pancras was eventually completed and the new library was opened by HM The Queen in June 1998. Correspondence some years later, concerning arrangements for the launch event of The Whole Woman on International Women’s Day, 8 March 1999, indicates relations with librarians had been happily restored. The launch was scheduled to be held at the British Library, but appears to have been cancelled in solidarity with industrial action by British Library staff on their working conditions.[15]

The landscape of libraries has radically changed and continues to change, with constant questioning and redefining of operating environments, roles, functions, and funding. In the digital environment, where library resources are increasingly able to be accessed remotely and libraries may no longer need to be physically visited to be used, academic campuses are investing in “The sticky campus” [architecture and facilities] “designed to attract if not tether a wireless-digital-era student…” [16].

The Greer Archive provides insights on libraries from the perspective of a highly skilled and dedicated scholar, and confirms the ongoing role and importance of specialised collections and the knowledge of their curators and librarians to researchers like Greer. Perhaps the question for the future of libraries is whether it is researchers like Greer who will become an increasingly rare breed?

The last words also belong to Greer, the reader and researcher, the connoisseur and, sometimes quixotic, supporter of libraries. For Germaine Greer, “A library is a pleasure dome, bulging with honey dew and dripping with the milk of paradise…If readers had their way they would build nests in the stacks and sleep pillowed on the books that have meant most to them, drugged with the scent of words.” [17]

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of the “Greer Team” in preparing this blog. My grateful thanks to former assistant archivist Dr Millie Weber who made the Correspondence with Libraries series accessible with her elegant listing; assistant archivists Lachlan Glanville, for pointing me to Greer’s provocative writing about the British Library of the 1990s, and Kate Hodgetts, for the beautiful photographs; special thanks to Dr Rachel Buchanan, Curator, Greer Archive, for her unfailing support and confidence in me and all her colleagues.

[1] Germaine Greer. Daddy, We Hardly Knew You. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1989 p. 70.

[2] Ibid. p.69,71

[3] SLV Reference: MS 1287: Index cards containing information on the Greer family tree, compiled during research for the book ‘Daddy we hardly knew you’ (1990)

[4] Daddy, We Hardly Knew You.p.239

[5] Series 2014.0039: Research and Reference Card Indexes contains index cards for The Female Eunuch and other works. All cards in this series have been digitised.

[6] Germaine Greer, ‘Flashy Libraries? I prefer to get my adventure out of the books not the building;’ The Guardian, 12/2/2007. Item 2014.0046.01091, Unit 21

[7] Publishers UK: Shakespeare’s Wife Paperback Edition Bloomsbury [Germaine Greer to Katie Bond, Sky Book Show, 23/10/2008]. Held in Item 2014.0052.00004, Unit 1

[8] Folger Shakespeare [Library – Correspondence]. Held in 2017.0004.00025, Unit 2

[9] Belvoir Castle [Correspondence, 11/9/1995]. Held in Item 2017.0004.00006, Unit 1

[10] Bodleian [Library – Correspondence]. Held in Item 2017.0004.00010, Unit 1

[11] TV One Foot In The Past 29/6/94 [Greer draft script]. Held in Item 2017.002.00153, Unit 4

[12] Germaine Greer, ‘Why Tim Clist should have had a year out’, The Independent, Oct 2000. Item 2014.0046.00633, Unit 11

[13] Germaine Greer, ‘Book up for a long hot summer in library land’, The Guardian, 30/5/1994. Item 2014.0046.00375, Unit 6

[14] TV One Foot In The Past 29/6/94 op.cit. Greer’s view of a “war” between readers and librarians was strongly refuted by Anthony Kenny Chair, British Library Board (AK/GG, 8/8/1994. Held in Item 2017.0004.00012)

[15] Publishers UK: [Transworld] The Whole Woman – Launch Event 8/3/1999 [GG/Marianne Velmans, 8/3/1999]. Held in Item 2014.0052.00043, Unit 3

[16] Ray Edgar, ‘Look and learn’, The Age 22/7/2017.

[17] TV One Foot In The Past 29/6/94 op.cit.