Women’s Liberation and Feminist Sources at UMA

Sue Fairbanks, Acting University Archivist

When Germaine Greer visited Australia in 1971 to see her family and promote the paperback edition of The Female Eunuch, the Australian women’s movement was gearing up for one of its most important interventions in Australian politics. The Women’s Electoral Lobby, convened by Beatrice Faust, was formed to survey all candidates in the December 1972 Federal election on issues of interest to women, and to produce a form guide for voters. The election was won by the Labor Party under Gough Whitlam with its platform of progressive reform.

Papers from WEL in Victoria were the first from the second wave of Australian feminism deposited in the University of Melbourne Archives in 1974. They were followed by records from the Women’s Liberation Movement, Working Women’s Centre, Abortion Law Reform Association and from women involved in the fight for institutional equality and legal reform: Zelda D’Aprano, Jan Harper, Alva Geikie, Dulcie Bethune, Alma Morton and Joyce Nicholson.

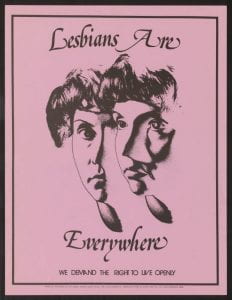

Not all women’s liberationists were beating a path to UMA’s door however. In 1982 a women’s liberation reading group was formed to study the movement’s history but members soon realised that documents were disappearing and that a concerted effort was needed to protect and archive them. The Women’s Liberation Archives had its first meeting on 1 March 1983 and met regularly for the next ten years while collecting, preserving and making material available for research. Its premises moved several times until the 1992 closure of the Women’s Liberation Building in Fitzroy meant the Archive was relocated to a private home. It was renamed the Women’s Liberation and Lesbian Archives to acknowledge the participation of lesbian feminists and separatist feminists in the women’s movement.

In 2000, a new collective was formed to find a permanent home for the Women’s Liberation and Lesbian Archives, and it registered as the Victorian Women’s Liberation and Lesbian Feminist Archives Inc. (VWLLFA). After exploring the options, a mutual decision was made to move the collection to the UMA.

From UMA’s point of view, the acquisition of the initial 126 collections making up the VWLLFA more than doubled, and significantly broadened, our holdings on the women’s movement. It increased the number of collections from women’s liberation organisations such as the Women’s Liberation Switchboard and the Women’s Liberation Centre. Uniquely, the acquisition provided an insight into lesbian feminist and separatist politics and their rich community life in Melbourne and Victoria. Lesbian publications such as Labrys, Lesbiana and Lesbian News joined Melbourne Women’s Liberation Newsletter and Vashti’s Voice on the Archives’ shelves. Collections such as the Lesbian and Women’s Community Theatre papers and the Performing Older Women’s Circus scripts join the records of more fundamental concerns such as the Matrix Guild addressing the issues facing older lesbians, particularly in the areas of health and housing, and the records of women’s refuges.

UMA has continued to collect records from the women’s movement in our own right as well as with the VWLLFA, and has developed several strengths intertwined with those discussed already. Women and publishing and women’s movement memorabilia are just two examples.

The UMA holds the records of McPhee Gribble Pty Ltd, a major publishing company run by Hilary McPhee and Diana Gribble from 1975 to 1989, as well as of the feminist publishing venture, Sisters Publishing Ltd, from 1979 to 1984. Sugar & Snails Press began life as the Women’s Movement Children’s’ Literature Co-operative Ltd in 1974 by women who were concerned about sexism in children’s literature and began to publish and write their own books. Lesbian feminist publishing is represented by the Lesbian Newsletter and its successors already mentioned. UMA also holds the papers of Susan Hawthorne and Renate Klein, publishers of Spinifex Press; and of the 6th International Feminist Book Fair held in Melbourne in 1994.

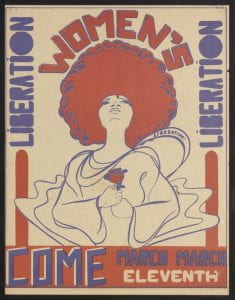

The VWLLFA collected and transferred to UMA a vast number of posters from women’s movement events from the 1970s on; as well as related t-shirts, banners and photographs. Collections of women’s alternative music on vinyl recordings are also held, although they are not yet available for access.

Finally, the union and labour movement records held at UMA document the long history of the struggle for the rights of women as workers. They include company and union records on the 1907 family wage decision, the many campaigns for equal pay, the establishment of female-only unions and many other industrial campaigns and issues.

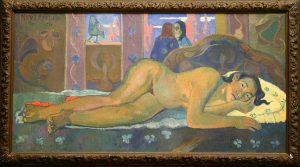

The feminist holdings of UMA doubled again with the acquisition of the papers of Germaine Greer in 2014, making the UMA one of the larger Australian holders of second wave feminist and lesbian feminist archives alongside:

- Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives http://alga.org.au/

- Jessie Street National Women’s Library http://www.nationalwomenslibrary.org/

- Adelaide Women’s Liberation Movement Archive (1984-2009) at the State Library of South Australia, http://www.slsa.sa.gov.au/

- Lespar Library of Women’s Liberation and the Gay and Lesbian Archives of Western Australia at the Special Collections of Murdoch University Library, Western Australia http://library.murdoch.edu.au/Researchers/Special-Collections/

- State Library of NSW for the records of feminists and the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Grah http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/

And international archives:

- The June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives in West Hollywood, California, http://www.mazerlesbianarchives.org/

- The Lesbian Herstory Archive in New York http://www.lesbianherstoryarchives.org/