125 years of horticultural education – celebrating Burnley Campus

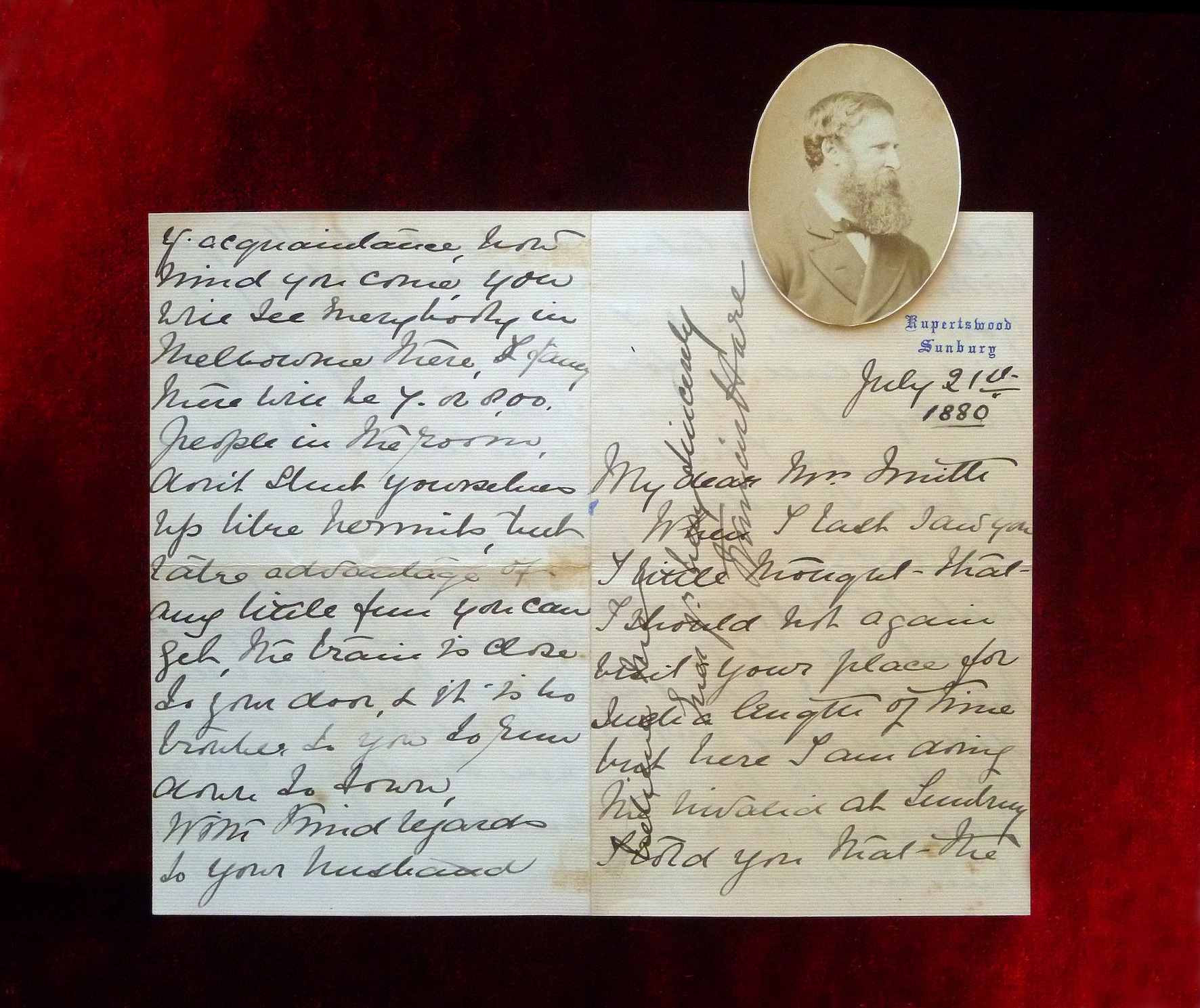

Subsoiling in East Orchard July 1918. Burnley Archives, Photographs of Burnley School of Horticulture and Subsequent Entities 2011.0023, B09.0003(8)

Mowing Burnley Gardens, 1891-1893, Burnley Archives, Photographs of Burnley School of Horticulture and Subsequent Entities, 2011.0023.0256

Jane Wilson

Volunteer Archivist, Burnley Archives

Friends of Burnley Gardens

The last few weeks have been very busy for me, the Volunteer Archivist for the Burnley Archives Collection. The Burnley Campus is celebrating this year 125 years of continuous horticultural education and it has been 25 years since the Archives were formally set up. The Archives were established when A. P. Winzenried was commissioned to write a history of the Burnley Gardens and material had to be gathered and put together for him to use. All past students and staff who could be found were asked to send in memorabilia and what a treasure trove arrived. Hundreds of photographs, letters, documents, artefacts, registers and student work had to sorted and stored. The book was written and cataloguing started but there was far too much to be dealt with quickly. Elizabeth Hill became the first Volunteer Archivist and established the cataloguing system. Two former Principals endeavoured to describe the old photographs and recall events from the past. Joss Tonkin, another volunteer, assisted Elizabeth Hill and later took over when Elizabeth retired from her voluntary position.

At this time the Archives were stored under the roof in an old wooden building that had once been the Dairy. It was very hot in the summer and cold in the winter; not ideal conditions. I remember as a trainee Guide for the Friends of Burnley Gardens in about 2005 visiting Joss and having to put on white gloves while she showed us some of the treasures like enormous registers with handwritten lists of the hundreds of fruit trees that had been planted in the Orchard in the 1870s or the jodhpurs that the girls wore as their uniform in the 1920s.

By 2009 Joss wanted to give up her voluntary position and I offered to take over. It was a daunting prospect – there was so much work still to be done and it had been decided to move the material to the Main Administration Building where conditions were better. They are now housed in what had been the girls’ changing rooms. My first task, after moving everything out of the Dairy, was to catalogue onto a spreadsheet and digitise the photographs. I have been doing this for over six years now and I am still not finished as I have been encouraging people to keep donating material to the Archives and every time an office is cleared out I go in searching for more. One particularly hot summer found me in the former Egg Curator’s house rummaging through the recycling bins to find things I thought worth archiving.

The other reason why cataloguing is such a slow process is that the Burnley Archives are used by staff, students, museums and the general public on a regular basis. The University of Melbourne Archives is progressively cataloguing descriptions of the Burnley Archives holdings into its database but most of the catalogues and photographs are still not accessible other than from the computer in the Burnley Archives. There are, however, more volunteers working in the Archives now. Judith Scurfield, former Head of Maps at the State Library, does cataloguing and helps me with general advice, Mary Eggleston, a former science teacher helps with general packaging of maps and sorting, and Ala Shtrauser, former Assistant Librarian at Burnley sorts photographs and identifies people in them.

A typical day would have me looking for and emailing photographs of someone’s mother who had been a student in the 1930’s – and reading the grateful email in reply. A student might ask me for plans of a garden area and any additional documents we had. A staff member might ask me to talk to a group of students to let them know what was available for them to use. A very regular visitor to the Archives is the Garden Co-ordinator, Andrew Smith. The Burnley Gardens are Heritage Listed and he has to maintain them under strict controls. This means that every time he replaces a plant or does any work in the Gardens he has to refer to the Archival documents and photographs. We can literally spend hours looking at photographs deciding where and when they were taken and whether that area could be restored to its original condition.

We are continually adding to our knowledge of the history of the Gardens and College. So much of it is oral history and it has to be recorded now while those with memories are still alive. The Friends of Burnley Gardens was set up in the late 1990s in part to provide funds for the maintenance of the Gardens. In recent years much work by the FOBG has gone into gathering together information, much of it oral, on the people who have been involved in designing different parts of the Gardens.

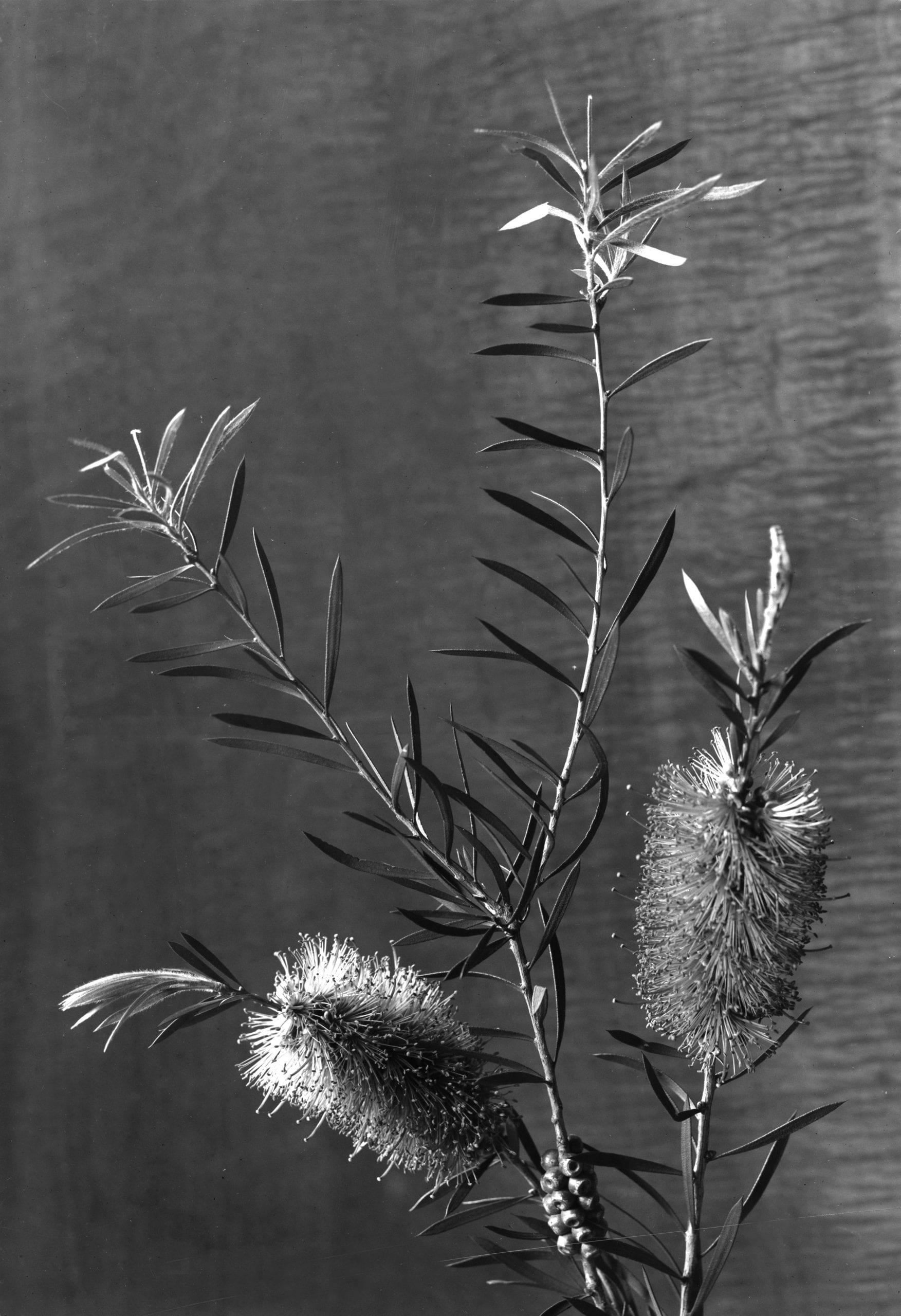

As a joint venture between the University and the Friends an app is being prepared to enable visitors to Burnley Gardens to walk around listening to the rich history of the Gardens and College and descriptions of some of the interesting plants.

At the moment I am also assisting staff prepare for their entry in the Melbourne International Flower and Garden Show in March where they are presenting a snapshot of Burnley’s influence on garden design. I also conduct tours for the Friends of Burnley Gardens: http://www.fobg.org.au. Come and visit us.

Sue Fairbanks

Deputy Archivist – University of Melbourne Archives

Research and Collections, Academic Services and Registrar

In the long loop of the Yarra River where Riversdale Road continues as Swan Street, with the noise of the Monash Freeway as a constant backdrop, lies one of Melbourne’s peaceful and beautiful gems. The Burnley Gardens, part of the Burnley Campus of the University of Melbourne’s School of Ecosystem & Forest Sciences, is an oasis known to generations of Melbourne’s garden enthusiasts both amateur and professional. Indeed it is where horticulturalists and garden designers have been educated since the inception of the Burnley School of Horticulture by the Victorian Department of Agriculture 125 years ago.

Teaching of horticulture commenced in 1891, but the site itself was established long before. Here in 1836 a Richmond Survey paddock was reserved to graze Survey Department animals, and in August 1862 most of the area was reserved as public parkland known as Richmond Park. In late 1860 the Minister of Lands granted the (later Royal) Horticultural Society 25 acres of the eventual Park for the purpose of testing and acclimatising introduced fruit trees, vegetables and exotic garden plants for producing crops in Victorian conditions. The Gardens themselves were opened in January 1863 and the Horticultural Society continued their development until in late 1890 it handed back the grounds to the Victorian Government and its Department of Agriculture in return for cancellation of its debts. When the Burnley School of Horticulture was opened in May 1891 it was the first Horticultural College in the Southern Hemisphere and one of the first in the world.

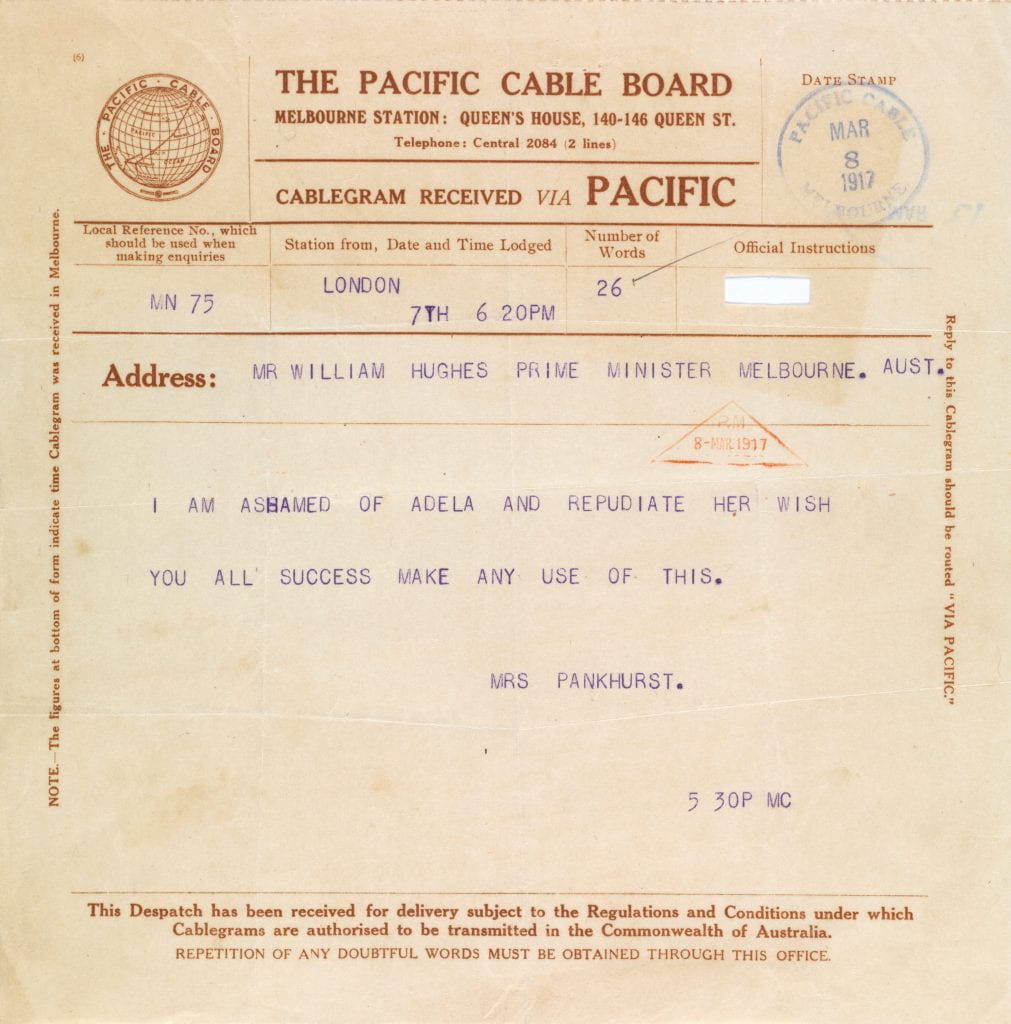

This year the School of Ecosystem & Forest Science is celebrating the 125th Anniversary of continuous horticultural education at Burnley with a program of gardening events detailed at http://ecosystemforest.unimelb.edu.au/burnley125years. But there is another, smaller, anniversary which deserves to be remembered this year: the 25th Anniversary of the establishment of the Burnley Archives (BA), repository of photographs and documents which help us remember and celebrate the last 125 years. Volunteers catalogued the approximately fifteen metres of archival records using a standard designed by the first archivist and this system was used consistently since the inception. The Archives contain a mixture of official records (principals’ administrative records and student registers), photographs, deposits from former students including student clubs, and ‘artefacts’ such as ploughs, jodhpurs and a leadlight window.

In 2011 Jane Wilson and supporters of the Archives at Burnley contacted the University of Melbourne Archives (UMA) for advice. The BA needed support for preservation materials and electronic cataloguing of the many volumes of handwritten entries that formed the main finding aid. UMA agreed to supply preservation storage materials, and also to analyse and advise on producing a machine readable catalogue. Supporters of the Burnley Archive made it clear that they wanted the material retained at Burnley and not whisked off to the UMA store in Brunswick. Thus was born a cooperative project to hold the archival material at Burnley, but to catalogue it in the database of the UMA and make it discoverable through their online interface. In the language of the day, it became part of the ‘distributed archive’ of the University. Jane Wilson and her volunteers began typing the handwritten catalogues into spreadsheets for upload into the UMA database. So far six collections from the Burnley Archive are described in it; all except the photographs are described in detail.

The most interesting of these are undoubtedly the photographs, but the Registers and Books are fascinating. This series contains the earliest record of the fruit planted at Burnley initially by the Royal Horticultural Society of Victoria and later by the Burnley School of Horticulture. The registers are in the main handwritten and detail the planting and harvesting of currants, almonds, figs, nectarines, peaches, apricots, cherries, plums, apples, pears in the garden often with their original locations. Later registers cover eggs, milk and livestock. Plant records are also found in the Student Registers where both plants and students have been recorded in the same volumes. The books also described in this series are generally gardening or botany books used by the early staff and give an insight into gardening trends through the century.

To see the catalogue entries and lists of material held and accessible in the BA, go to the University of Melbourne Web Site at http://archives.unimelb.edu.au/ and search on Burnley Archives in the Catalogue. Note that access to the Archives at Burnley is by appointment on a Tuesday. It is well worth a visit not only to meet Jane and research the Archives but also to sit in the Summer House and contemplate the Lilly Ponds. You will feel amazingly refreshed.

| Title | UMA Reference Number |

| Artefacts Of Burnley School Of Horticulture | 2015.0058 |

| Photographs Of Burnley School Of Horticulture And Subsequent Entities | 2011.0023 |

| Maps And Plans Of Burnley Gardens And Campus | 2015.0068 |

| Horticultural And Livestock Registers And Books | 2015.0059 |

| Registers Of Student Enrolment And Results | 2015.0060 |

| Certificates And Report Cards | 2015.0065 |