Business as usual: correspondence from the Bright Family Papers

Nell Ustundag (PhD Candidate in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne)

Nothing is quite like handling and reading original hand-written correspondence. Letters, particularly those written by hand, are intimate, tangible evidence of relationships between and amongst people; autobiographical evidence of the perspectives and lives of their writers. Most people cherish and collect letters received, yet in today’s overly digital world, the craft of letter writing has given way to email correspondence – emails are editable beyond compare, and instantly gratifying, sent and received in timeframes unimaginable to earlier generations. I myself still struggle to come to terms with the fact that I can write to my twin brother in Washington DC and receive a response within seconds.

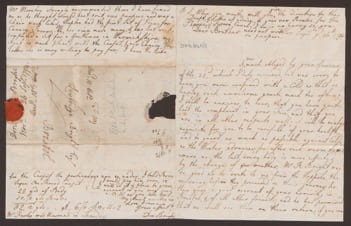

The letter that forms the subject of this blog post was written from Bristol, England in September 1815, by L&R (Lowbridge and Richard) Bright, and is one of many letters in the Bright Family Papers held in the University of Melbourne Archives. This letter – addressed to JC Pownall Esq., in Jamaica – provides an interesting window both into both the commercial correspondence and legal rhetoric of the early 19th century. The quality of legal vernacular, used by the letter’s authors in an accomplished manner, immediately impressed me. The subject of the letter is that of a number of debts and the terms for their repayment and settlement. JC Powell Esq appears to be a lawyer representing the interests of someone at odds with the author, perhaps the debtee, a Mr W Anderson. There seems to be a debtor’s triangle with Mr Patterson and L&R Bright both owed money by Anderson, who owns a property called Bryants Hill, against which debts have been secured and mortgaged. Clearly, there are complicated commercial relationships at play.

The structure of the letter, I found entertaining, although I had the uneasy feeling that the authors were both intelligent and cunning. The authors begin by thanking the addressee for the ‘esteem’d favour’ of a previous letter and the family’s ‘full approbation’ of the proposed settlement. After summarising the terms of both debts, L&R Bright turn to points their ‘party’ would like added to the settlement. They refer to the apparent delinquency, or lack of punctuality, in repayments to date, as well as the age of Mr Anderson (the debtee) and the possibility of his decease.

L&R Bright’s tone suddenly changes when they emphasise how much their party has already provided, particularly in the form of ‘consenting to such remote instalments’, as well as to the fact that they had already counselled Anderson to make arrangements for repayments in the past. There is no mistaking the full strength of L&R Bright as businessmen, and by the final few paragraphs, they are advising the lawyer about an appropriate course of action to further secure both debts (one owing to them and another to Mr Patterson).

Scattered throughout the letter, are comments, or perhaps threats, regarding the importance of avoiding the Law or Court proceedings. Similar to sentiments today, the more appealing and amicable method of conflict resolution in the early nineteenth century was to settle out of court.

This letter and the others in the Bright Collection, would be of interest to people interested in a range of topics, including Jamaican history, early 19th Century Caribbean business and economic history, slavery, and of course, the Bright family.

Having read the letter several times, I wonder how the correspondence continues and concludes. Would the repayment schedule continue? Do L&R Bright get paid? I am curious about the episodes yet to unfold in the Bright family saga – what happens after Richard Bright inherits the Meyler estates in Jamaica in 1818? How will the inheritance disputes with the Meyler family end? What happens to the estates as a result of the forthcoming abolition of the slave trade and subsequent years of economic decline in Jamaica and the Caribbean? So many questions might be addressed by further readings of the many items in this wonderful archive.