Fletcher Jones ‘Pleasant Hill’ Water Tower (otherwise known as the ‘Silver Ball’)

In late 2014 the University of Melbourne Archives UMA acquired Ralph Jones’ 1975 Engineering Awards Competition submission ‘Elevated Steel Water Tower and Associated Project and his papers about the construction of the water tower at ‘Pleasant Hill’, (otherwise known as the ‘Silver Ball’) at the old Fletcher Jones Factory site, Warrnambool. The water tower is an iconic and distinctive feature in the Warrnambool local area and is a useful landmark for the visitor as they enter the town. In discussions with Ralph Jones his motivation for depositing his collection with the Archives is to ensure others are aware of the design and construction method used to build the tower and to raise awareness about the factory site’s significance.

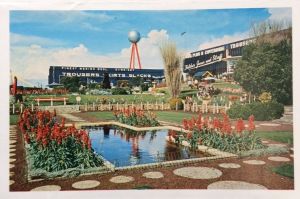

The elevated steel water tower has an attractive appearance which enhances the famous landscape and garden setting of the Fletcher Jones & Staff Pty. Ltd. Production centre, “Pleasant Hill” at Warrnambool. The water tower is 37.8 m (124 ft.) high with a total capacity of 205,000 litres (45,000 gallons). It is in the form of a sphere 7.32 m (24 ft.) diameter, supported on three lets each 0.76 m (2’-6”) diameter.

As space was at a premium, the design permitted the base frame of the water tower to be incorporated in the factory fabric.

The Ralph Jones Water Tower Collection is now available for research access.