An Apothecary’s Annotations: Eighteenth-Century Medical Notes in a Seventeenth-Century Text

Since 2009, the rare books collection of the Brownless Medical Library has been housed by Special Collections in the Baillieu Library. This collection, which numbers 1,850 volumes, is strongest in eighteenth and nineteenth-century material. Some earlier texts are also held, such as sixteenth-century editions of the Galeni librorum quarta classis and La farmacopea o’antidotario dell’eccellentissimo Collegio de’ signori medici di Bergomo (both published in Venice, 1597) and a copy of the 1698 edition of John Browne’s Myographia nova, or, a graphical description of all the muscles in the humane body.[1]

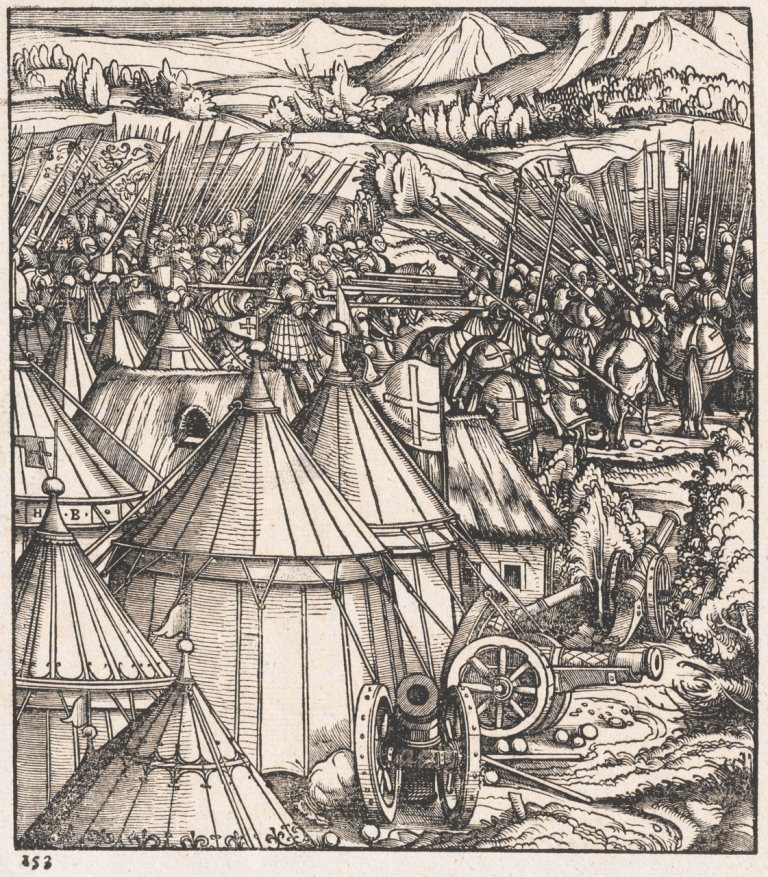

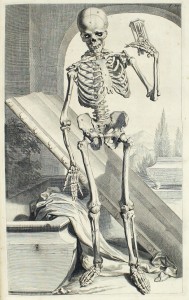

Another seventeenth-century anatomical text in the collection is William Cowper’s The anatomy of humane bodies, printed in Oxford for Samuel Smith and Benjamin Walford, printers to the Royal Society, and published the same year as Browne’s 1698 Myographia nova.[2] Cowper’s book is known for its folio-sized anatomical plates by Gérard de Lairesse previously published in Govard Bidloo’s Anatomia humani corporis (Amsterdam, 1685), which caused a vitriolic exchange between the two anatomists after Bidloo accused Cowper of plagiarism.[3]

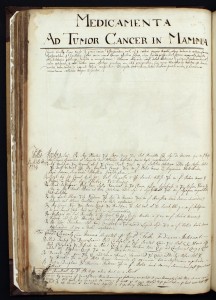

What makes the Melbourne copy of Cowper’s Anatomy particularly interesting are the copious notes written between 1724 and 1740 by an English apothecary, who compiled a combination pharmacopeia and prescription book on the blank versos of sixty-two plates.

The notes refer to treatments for thirty-four diseases or groups of diseases, such as rheumatism, asthma, dysentery, pulmonary tuberculosis, and cancer. In her 2008 study of the book, Dorothea Rowse (Honorary Fellow of the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies and former Sciences Librarian) described the notes as consisting of ‘a comprehensive list of available remedies, evidence of remedies that had been used for named patients, a guide to the physicians recommended for particular medical conditions … and a record of patients who had been treated for serious medical illnesses’.[4]

The inclusion of named physicians and patients, some of whom were children, add a very real, very human element. Rowse counted fifteen physicians whose names appear in the notes, along with the names of ninety-three identifiable patients who lived in the vicinity of the village of Hambledon in the county of Hampshire.[5] Her research suggests the author of the notes was Edward Hale, an apothecary and barber surgeon, resident in Hambledon from 1720, whose son (also Edward) continued the practice.[6]

To make these notes available widely available to researchers, each page has been photographed and the images uploaded to Flickr:[7]

https://www.flickr.com/photos/uomspecialcollections/sets/72157647386329921/

Unfortunately, due to the book being rebound, some of the notes run into the inner margin. Anyone consulting the notes is welcome to contact Special Collections at special-collections@unimelb.edu.au for assistance.

Dorothea Rowse’s full account is available on-line as a PDF at the following URL:

https://www.unimelb.edu.au/culturalcollections/research/collections3/rowse.pdf

Anthony Tedeschi (Deputy Curator, Special Collections)

[1] The Melbourne copy of Browne’s Myographia nova is from the Chatsworth House library of William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire (1640–1707). The text was first published in 1681.

[2] Cowper’s The amatomy of humane bodies (London, 1698) purchased with funds from the estate of F. M. Meyer.

[3] Cowper mentioned neither Bidloo nor de Lairesse in his text. According to Cowper’s ODNB entry, Bidloo ‘published a complaint in 1700 addressed to the Royal Society accusing Cowper of plagiarism … which included copies of letters to Cowper, most of which had gone unanswered, correspondence with his publishers, and a list of errors. The Royal Society, with some discomfort, declined to adjudicate on the matter’.

[4] Dorothea Rowse, ‘The Hampshire Apothecary’s Book: An 18th Century Medical Manuscript in the Baillieu Library’. University of Melbourne Collections issue 3 (Dec. 2008), p. 13.

[5] Ibid, p. 15.

[6] Ibid, pp. 16-17.

[7] To view the original or larger-sized images, single click on the ‘Download this photo’ icon towards the lower right, then select ‘View all sizes’ (‘Large 2048’ file size option is recommended).