A Small World of Bookplates

In 1996 the Baillieu Library showcased its small but captivating holdings of bookplates with the exhibition The Age of Ex Libris.[1] The exhibition focused on the period from the 1890s to the 1930s when a number of societies devoted to bookplates were established and the Library displayed works from the holdings of Harold Wright who collected Lionel Lindsay bookplates and those donated by Neville Barnett in 1936.

[Percy] Neville Barnett is recognised as one of the earliest authorities on bookplates in Australia. The information about his 1936 gift was not recorded in the database, but it has been possible to identify many of those works from the finely printed publications Barnett produced, in particular his Wood-cut bookplates (1934). This privately printed book reveals the international breadth of his collection, and reflected in his gift which includes examples from Czechoslovakia, Germany, Italy and America amongst others. Mounting political tensions are seen in some of these 20th-century bookplates as the world moved toward its second international war. Neville Barnett had in his collection bookplates designed for Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini; one of the Mussolini bookplates is held by the Baillieu Library.

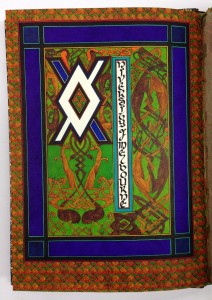

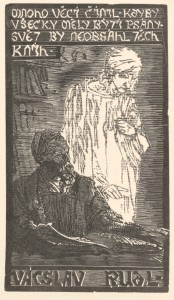

The Australian Bookplate Society was formed in 1923 and Barnett was a founding member along with other collectors such as Camden Morrisby. Thebookplate designed by Lionel Lindsay for Morrisby which depicts the incident where Samuel Johnson wallops a London bookseller with a dictionary, ‘became highly sought after and gave its owner access to bookish individuals around the world’.[2] Appreciation for bookplates freed many international boundaries; Vácslav Rudl was a Czechoslovakian collector and also a member of the Australian Bookplate Society.

The inscription on his bookplate translates: ‘He was involved in many things;/ If all these should be written down,/ The world would not hold all the books’.[3] The often personalised visual meanings in bookplates can also emphasise their specialist audience. While the symbols and inscriptions in bookplates and their wider purpose as labels for book ownership demonstrate that a world of knowledge may be communicated through these miniature printed forms.

Kerrianne Stone (Special Collections Curatorial Assistant (Prints))

[1] [Geoffrey Down and Judith Purser], The age of ex libris: bookplates from the Library’s collection: an exhibition, 6 February – 30 April 1996, Leigh Scott Room, Baillieu Library (Melbourne: Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne, 1996).

[2] Mark J. Fenson, ‘A Bibliography Works by and about P. Neville Barnett,’ in Mark J. Fenson (ed.) P. Neville Barnett: Australian genius with books: a volume of essays issued on the 50th anniversary of his death (Riverview, NSW: Book Collectors’ Society of Australia, 2003), p. 59.

[3] Down and Purser, [p. 28].