Henry Jones IXL ‘Knight of the Jam Tin’

A finding aid for another of our collections is now available, thanks to the fine work of our archivists. The records come from Henry Jones IXL and its many subsidiaries and merged firms. The collection spans 83 shelf metres and dates from 1846 to 1974. It includes minutes, correspondence, staff and financial records, publications, photographs and much more. For further detail about the collection search for 1974.0056 Henry Jones IXL

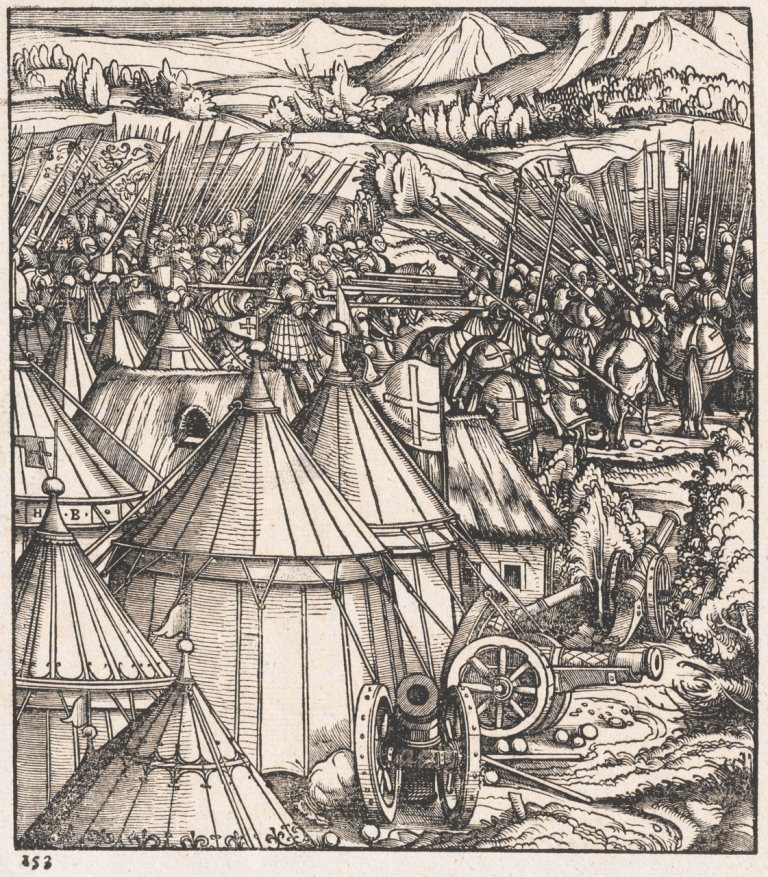

Undated

1974.0056 Henry Jones (IXL) Ltd, Unit 829

Henry Jones (1862-1926) began work aged 12, at George Peacock’s jam factory on the Old Wharf, Hobart pasting labels on tins, within a few years he had become an expert jam-boiler. When Peacock retired in 1889, Jones formed a partnership and took control of the company, renaming it as H. Jones & Co. In 1902 the partnership dissolved but the company name was retained as the business grew and diversified into mining and briefly, shipbuilding. Jones was knighted in 1919, in recognition of his war efforts. Accordingly, “Jam Tin Jones” became known as the “Knight of the Jam Tin”

The brand name ‘IXL’ is a play on ‘I excel’. The Melbourne arm of the business was located in Prahran, in premises still know as The Jam Factory.

1974.0056 Henry Jones (IXL) Ltd, Unit 830

The IXL factory is just out of fram, centre left.

The site of the Henry Jones IXL factory is now the Henry Jones Art Hotel which will display a selection of images from the Henry Jones IXL collection at their Hobart premises. The hotel includes a lively pub and events space within the original structure of the building. The words ‘H Jones & Co Ltd’ ‘IXL Jams’ remain on the facade as a reminder of past use and Henry Jones’ contribution to industry and community in the local area.

Links:

Australian Dictionary of Biography – Henry Jones

Contributor: Sophie Garrett