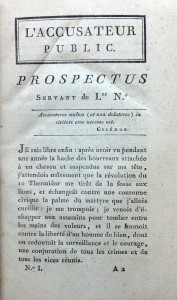

New Acquisition: L’Accusateur Public (French Counter-Revolutionary Journal)

Special Collections recently acquired a complete set of one of the most influential French counter-revolutionary journals: L’Accusateur public. Only a few issues are available on-line through Gallica (the digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France), and the only other recorded set in the country is held by the National Library of Australia, making the University of Melbourne copy a valuable resource for students and scholars, and a fine addition to our holdings of material on the French Revolution.

L’Accusateur public was founded by the Jean Thomas Élisabeth Richer-Sérisy (1759–1803) shortly after his release from prison on 27 September 1794. Printed in Paris by Mathieu Migneret, the journal ran for thirty-five numbered issues until 1797 and brought Richer-Sérisy considerable popularity as a public writer.[1]

Such notoriety of course did not go unnoticed by Revolutionary factions, nor did the fact that Richer-Sérisy’s energetic and vehement writing barely hid his Royalist opinions. His L’Accusateur public even outsold some of the pro-revolutionary periodicals, such as the Journal universal.[2] The year after The Directory seized power in the Coup of 18 Fructidor an V (4 September 1797), Richer-Sérisy was sentenced to deportation to Cayenne, French Guiana. He escaped and eventually made his way to England where he spent his remaining years. The last issue he edited (No. 35), dated 1 Frimaire an VII (21 November 1798), was seized by the police.

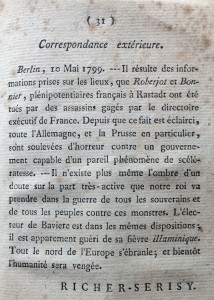

The acquisition also included the two unnumbered, counterfeit issues that appeared after No. 35.[3] The first is dated 6 Thermidor an VII (24 July 1799). Unlike the numbered series, Richer-Sérisy’s name is nowhere to be found, since he had already fled from France. According to Brunet’s Manuel du libraire … (Paris, 1860-1865 ed.), the issue was instead edited by the pro-royalist general Louis Michel Auguste Thévenet Danican (1764-1848).[4]

Perhaps without Richer-Sérisy’s name the issue failed to sell widely, for when a single issue of a second series appeared, possibly edited by Danican, it closed with a reprinted letter by Richer-Sérisy dated ‘Berlin, 10 Mai 1799’. Richer-Sérisy, however, upon reading or hearing about the issue, declared it a forgery.[5] Its editor(s) presumably used his name as an attempt to give the new series credibility and popular appeal.

A final point about the Melbourne copy not mentioned in the sale catalogue. On the recto of the first issue half-title is a rather worn ownership stamp, that of the Comte Joseph-François de Kergariou (1779-1849), bibliophile, prefect of Indre-et-Loire, and Napoleon’s chamberlain.

Anthony Tedeschi (Deputy Curator, Special Collections)

—-

[1] Although the final issue is numbered ’35’ there are actually thirty-four volumes in total. Issue No. 13, which was to contain an account of the battle between Revolutionary and Royalist forces in the streets of Paris on 13 Vendémiaire an IV (5 October 1795), was never published (perhaps not even Richer-Sérisy could spin the Royalist’s defeat). For more on its printer, Migneret, see Carla Hesse’s Publishing and Cultural Politics in Revolutionary Paris, 1789-1810 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) available on-line through the UC Press E-Books Collection (accessed 13.3.2014)

[2] Kenneth Margerison, ‘P.-L. Roederer: Political Thought and Practice During the French Revolution’ in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 1:1 (1983): 117

[3] The two unnumbered issues appear to be quite scarce. I was able to locate just three copies worldwide of the issue dated 6 Thermidor an VII and only two copies of the second series issue. No other copies are recorded in other Australian institutions.

[4] Charles Brunet, Manuel du libraire et de l’amateur de livres … 6 vols. (Paris: Firmin Didot frères, fils et Cie, 1860-1865), 6:1869-1870

[5] University of Pennsylvania Libraries catalogue: http://www.franklin.library.upenn.edu/record.html?id=FRANKLIN_13561 [No citation regarding the forgery comment given]