Nullius in Verba: The Royal Society’s Two Earliest Books

Earlier this week the Royal Society announced the launch later this year of Royal Society Open Science, an open access peer-reviewed journal publishing scholarly research in all fields scientific and mathematical. The move is seen by the Society’s president, Sir Paul Nurse, as a necessary step to keep pace with the changing face of publishing in the twenty-first century.

Changes in the publishing field is something the Royal Society has seen a lot of throughout its long history. The august body received a Royal Charter to publish relevant works in 1662 (two years after its official founding in November 1660), and will observe the 350th anniversary of its journal Philosophical Transactions in March 2015.

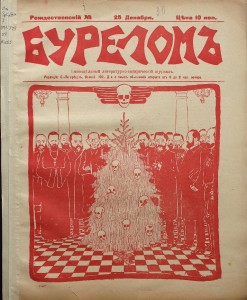

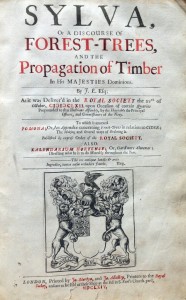

With the recent open access announcement and next year’s anniversary of Philosophical Transactions in mind, this week’s post highlights the Royal Society’s two earliest books: John Evelyn’s Sylva and Robert Hooke’s Micrographia; first editions of each are held by Special Collections.[1]

Sylva

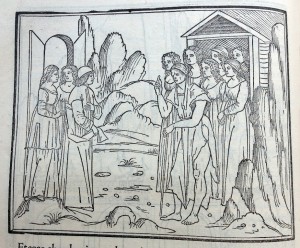

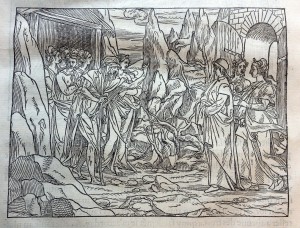

First printed in 1664, Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber was the first work sponsored officially by the Royal Society and the first treatise in English dedicated entirely to forestry.[2] Its author, John Evelyn (1620–1706), writer, intellectual and founding member of the Royal Society, is perhaps best known for his long-running diary kept from 1640 to 1706.

Evelyn initially presented Sylva as a paper to the Royal Society in 1662. The published text sought to encourage tree-planting after the destruction wrought by the Civil War and, it has been argued, to ensure a supply of timber for England’s developing navy and add a further boost to the economy. Evelyn’s book proved highly popular with its intended audience, namely the gentry and aristocracy, who took from it the idea of gardening as an aesthetic pursuit, and his discourse was positively received on the Continent where it stimulated new methods of forest management.[3] Today Sylva is recognised as one of the most influential works on the subject of tree conservation.

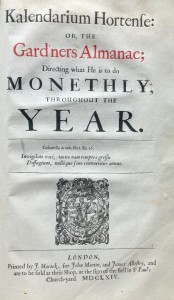

The first edition of Sylva contained two appendixes: Pomona: or, an Appendix Concerning Fruit-Trees in Relation to Cider, one of the earliest English essays on cider, and the Kalendarium Hortense: or, Gard’ners Almanac: Directing What He is To Do Monethly [sic] Throughout the Year, which was often reprinted separately and proved to be Evelyn’s most popular work.[4]

Micrographia

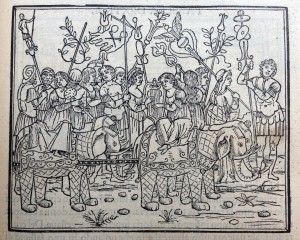

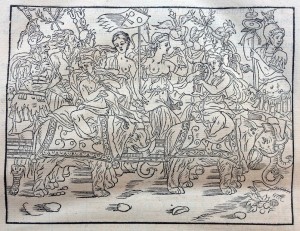

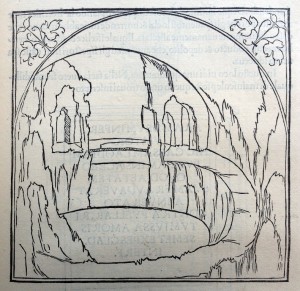

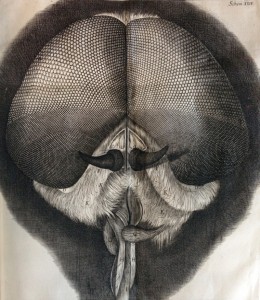

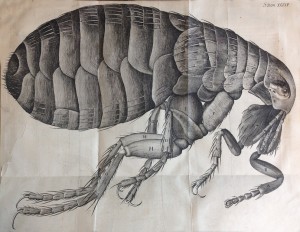

The second text printed for the Royal Society was Robert Hooke’s groundbreaking Micrographia, or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, published in 1665. Hooke (1635–1703), a natural philosopher and polymath, perfected the compound microscope and put the instrument to good use. His observations touched on a number of subjects, from combustion and diffraction of light, to fossils and artificial silk, and his description of the honeycomb-like structure of a cork gave us the word ‘cell’ to describe the basic biological unit of living organisms.

Micrographia is perhaps most widely known today for its illustrations. The book includes 57 microscopic and 3 telescopic observations, describing for the first time ‘a polyzoon, the minute markings of fish scales, the structure of the bee’s sting [and wings], the compound eyes of the fly, the gnat and its larvae, the structure of feathers, the flea and the louse’.[5] These enlarged images of such minute creatures (Hooke’s louse measures 45.7 cm in length) are as startling today as they must have been for Hooke’s contemporaries over 300 years ago.

Like Sylva, Hooke’s Micrographia was an immediate success. It was read by Samuel Pepys, who mentioned the book three times in his diary for January 1664/5 and called it ‘the most ingenious book I have ever read in my life’ (Pepys was also a member of the Royal Society).[6] The text, particularly Hooke’s observations on light and the spectrum, was also studied by Isaac Newton who drew inspiration from it for his Opticks: or, a Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light (London, 1704).

Anthony Tedeschi (Deputy Curator, Special Collections)

—

[1] John Evelyn, Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber (London: Printed by Jo. Martyn and Ja. Allestry, Printers to the Royal Society, [1664]); purchased by the Friends of the Baillieu Library

Robert Hooke, Micrographia, or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon (London: Printed by Jo. Martyn and Ja. Allestry, Printers to the Royal Society, [1665])

[2] Special Collections also holds copies of the 1670 second edition and 1679 third edition of Sylva, both of which were printed for the Royal Society

[3] http://royalsociety.org/events/2013/sustainability/ [Accessed 19.2.2014]

[4] Diana H. Hook and Jeremy Norman, The Haskell F. Norman Library of Science and Medicine, 2 vols. (San Francisco: Jeremy Norman & Co., Inc, 1991), i:271

[5] John Carter and Percy H. Muir, eds., Printing and the Mind of Man … (London: Cassell and Company Ltd., 1967 ed.), 88 (no. 147)

[6] Robert Latham and William Matthews, eds., The Diary of Samuel Pepys … 11 vols. (London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd, 1970-1976), vi:2, 17, 18