Marvin the Mobot and Shell: robotics history and oil exploration

Ary Hermawan

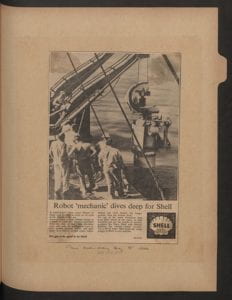

One of the most fascinating historical documents in the Shell Historical Collection stored at the University of Melbourne Archives is a press cutting of an advertisement placed in the Sun newspaper on Monday, August 19th, 1963. The ad features a photograph of a group of workers lowering the company’s Mobot — an underwater maintenance robot that can see with its “television eyes” and uses “its mechanical nose to turn screws and operate valves and grip pipes as it moves around under water.” Being lowered to the sea from a ship, the Mobot appears to be made to show the company’s technological prowess, with the robot being portrayed as “one of the many inventions that keep Shell ahead of the times.”

Continue reading “Marvin the Mobot and Shell: robotics history and oil exploration”