New exhibition and lightning talks: Horizon lines

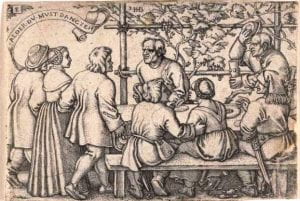

Horizon lines: the ambitions of a print collection is a new exhibition in the Baillieu Library. It is staged as one of the activities to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Harold Wright and Sarah and William Holmes scholarships, awards enabling print scholars from Australia or New Zealand to examine prints at the British Museum. The exhibition begins on the ground floor with a display on Harold Wright, London print seller and connoisseur, and the etchings from his personal collection. In the Noel Shaw Gallery on the first floor, the main exhibition unfolds with works of art from the Baillieu Library Print Collection featuring Northern and Italian Renaissance printmakers, such as Albrecht Dürer, and Dutch Republic prints, including Rembrandt, as well as the etching revival.

Come along on Tuesday 20th of August at 12:00 noon to hear print room interns speak about their discoveries and insights into selected prints in the exhibition.