Philip Sousa marches out of town

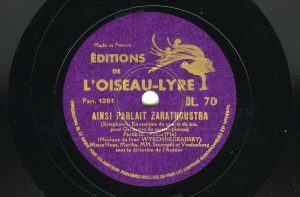

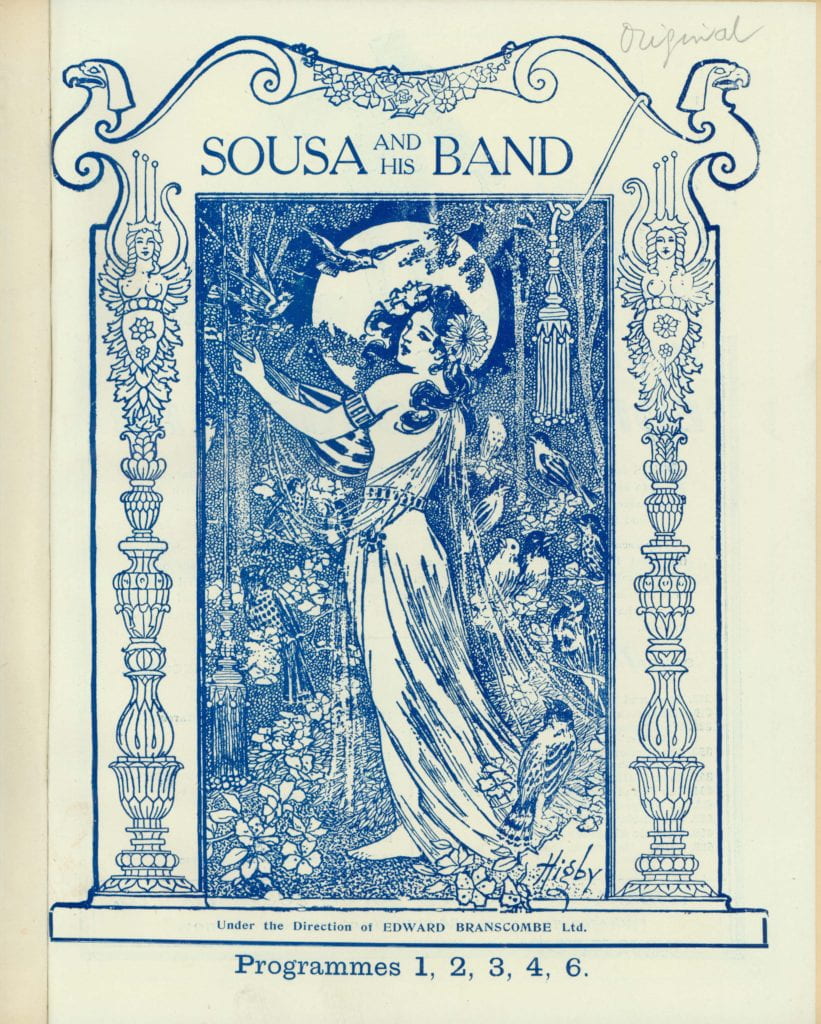

In 1911 Australian music lovers were treated to a lengthy tour by American composer and conductor Philip Sousa, along with his 55 piece band. The band toured the world for 352 days, and was at that time, the most extensive tour made by such a large band.

Most have likely heard Sousa’s distinctive style; mostly military and patriotic marches, although could not name him as composer. The official march of the United States of America, “Stars and Stripes For Ever” will have you marching with vigour, and was likely a stirring piece for Australian audiences.

Found in the Alex Whitmore collection are the 12 programs for concerts held in Australia. Melbourne’s July concerts in the Royal Exhibition Building were sell outs and the band played two concerts in Ballarat, before heading to the rest of the eastern cities and continuing to New Zealand. Sousa, ever the crowd pleaser and passionate composer, premiered a new march, “The Federal” on this tour, dedicating it to all ‘Australasians’.

Occupying an entire page in the program is a list of “Sousa Sayings”. Reinforcing his reputation as the most famous American composer of the Romantic –era these sayings include such gems as “A musical instrument is a good deal like a gun – much depends on the man behind it”, “Music, mathematics and babies are the only original packages”, and “The music of the future? To the man who writes there is no such thing; it is the music of the now”.

References: Sousa and his band, bound programs, c.1911, University of Melbourne, Alex Whitmore Collection, 1975.0065, Unit 1