Historic records are not relics – they are events unfolding

Stella Marr,

Archivist, University of Melbourne Archives

As an archivist, it is an all too common experience to see people puzzle over your stated profession. In conversation it is usually attended with a perplexed pause; in print, it is variously and excitedly read as anarchist, or interpreted perhaps more reasonably as activist.

When my inevitable exasperation subsides, I have to admit that on some level an archivist engages in a certain oblique activism. A repository of records is a breathing decomposing organism, which the hapless archivist attempts to control both its intellectual and physical integrity, and serve through advocacy, so that these records can be retained, re-read and reinterpreted in the future.

Research archives, such as the University of Melbourne Archives (UMA) are inaugurated by the right of access, unlike the archives of private companies or individuals. That is not to say there is anything innocent about collections, either in their creation, or in their carriage to a repository. Collecting is a deliberate act of inclusion – one that is guided by policy, influenced by politics and dependent on opportunity. Once in cold storage, papers remain in their original functional order, where they join the existing compressed body of past actions. It is here that the continuous activities and interests of individuals and organisations cease their frantic momentum.

It is round about this time my previously puzzled interlocutor, having ascertained the nature of my days becomes pensive and looks at me with something akin to pity – for surely nothing happens in an archive. “No, no – my friend – everything happens in an archive, let me explain.”

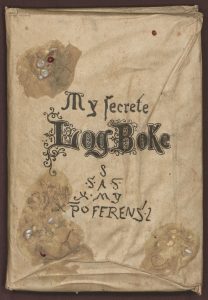

For an archivist – who lives their days immersed in the past – is to exist in the very unfolding of events – ‘you find nothing in the Archive but stories caught half way through: the middle of things; discontinuities.’ (1) Clothes worn to rags, skins of animals and pulp of trees, fibres joined to make paper, inscribed with instructions, memos, correspondence, maps, receipts, contracts, doodles, reports and notes. The material world transmuted and transmitting fragments of life – the cause of movement and actions in the world.

In walking the length of the repository – one passes records of the university, trade unions, insurance agencies, temperance & benevolent societies, records of settlers, merchants, scientists, butchers, chemists, funeral directors, theatre groups, career politicians, political activists, a few legitimate anarchists, architects and business in the supply of everything from photographs, lawn-mowers, biscuits, felt hats and copper. (2)

Over time as a research collection matures it develops not merely the quality or depth of its collection categories (such as ‘Trade Union’ holdings), but also the complex intersectional relationships between its collections. New acquisitions like the Australian Red Cross into UMA’s existing body of records creates an opening – very sobering view – of the nexus between Government policy, consumer demand, business interests, civil war, refugees and humanitarian organisations.

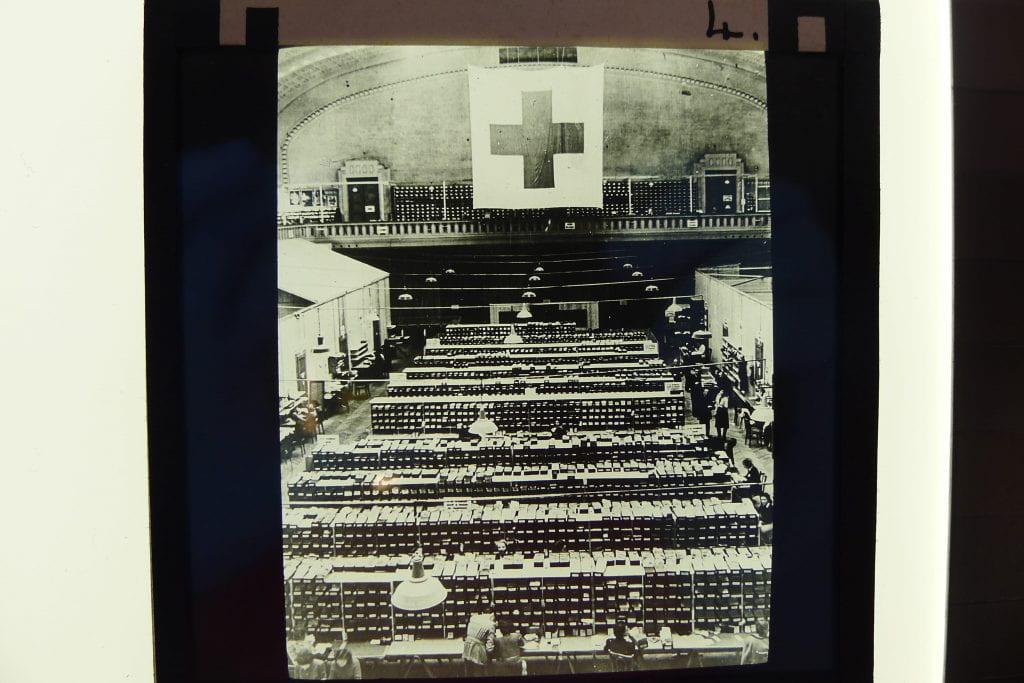

The records of the Australian Red Cross (which includes both the National Office as well as the Victorian Division) chart its activities over the last 100 years from a mere fledlging – into a mammoth organisation grappling with the extent of the humanitarian crisis resulting from the First World War. (3)

The complex factors that coalesced into in the First World War are many, but what is certain is that the territorial conflicts of competing Empires played a significant role. The 1880s was an era of amazing technical developments and equally astounding atrocities perpetrated by the demand for domestic goods, and the profits that could be made from their sale. The inflatable pneumatic tyre radically changed the aptly named “the boneshaker” bicycle. The consumer demand for this comfort – coincided with the rapacious ambition of King Leopold II of Belgium to own a slice of “magnifique gâteau africain.” He created a private company which from 1885 to 1908 controlled the Congo – ruthlessly enslaving and killing millions of people in the production of rubber for the European market. (4)

Photographer RG Casey, Oliver Holmes Woodward (1978.0079) collection, Unit 3, University of Melbourne Archives

A mere 4 km from Australian’s coast, the German New Guinea Company took control of eastern Papua New Guinea (including Bougainville) renaming it Kaiser-Wilhelmsland (1884-1914). Previously held under British colonial control, and with the outbreak of WW1, Britain tasked Australian forces to seize the German colony – resulting in our first military casualty of the war – a 28 year old Northcote electrician, ‘Billy’ Williams (1886 -1914). (5)

The Treaty of Versailles (1919) which divided German colonial territories between the allies charged Australia with the administration of Papua New Guinea – until it achieved independence in 1975. This period, and the records produced by creators of vastly differing interests, allow a view into the complex interdependence between government policy, business interests and humanitarian organisations (who often attend to the impact of philosophies and decisions of the former) – a site of fascinating research potential.

The Australian Red Cross collection, which occupies 374 linear meters, contains a diverse range of records including those of the Papua New Guinea Division of the Australian Red Cross, which operated from 1940-1972; records of the Field Force officers who served in embedded medical units with the Far East Land Forces (FARELF) in Papua New Guinea, Japan, Korea and Malaya, as well as records of the Bureau for Wounded, Missing and Prisoners of War in these theatres. Further records include disaster relief after the catastrophic eruption of Mt Lamington (1951); aid relief to civilians fleeing the Bougainville civil war, as well as development projects in its aftermath.

These records join existing collections pertaining to Papua New Guinea and Bougainville which include the diaries of Oliver Holes Woodward – mining engineer and prospector; records of the Bougainville Copper Limited as well as their managing directors; records of plantation owners; oral histories of Australian government patrol officers tasked with ensuring political stability; the records of Malcolm Fraser, Army Minister (1966-1971), Minister of Defense (1969-1971), Prime Minister (1975-1983) and founder of CARE Australia. Alongside these are the papers of legal professionals such as John Patrick Minogue who served the PNG Supreme court as a circuit Judge (1962-1969) and later as Chief Justice (1970-1974); as well as constitutional and economic advisors. Refer to the appended list of creators and series.

Bougainville Copper Limited, a subsidiary of Rio Tinto, owned and operated Panguna (1972-1989) which was once the largest open-cut copper mine – with the PNG government holding a 20% share. They made contracts with local communities – but entirely disregarded the matrilineal custodial system of land-care; this, coupled with the catastrophic environmental destruction caused by acid leaching into rivers which forced thousands to leave their land and homes, resulted in rebellion against the company which soon escalated into a civil war. (6)

Rio Tinto has since ceded their majority share – along with their responsibility for the environmental destruction – which is currently shared equally between the now Autonomous Region of Bougainville and the PNG government. The mooted reopening of the mine – this deep scar – coincides with Bougainville moving towards an independence referendum in 2019. Its developing economy is ironically underpinned by the very success of the resource business that has resulted in so much bloodshed and environmental devastation. (7)

Empires may have shrunk but the shadow of imperial legacies continues unabated for Bougainville, the Congo and other developing economies. Our era’s insatiable appetite for technological marvels, such as mobile phones and electronic devices, are entirely dependent on the primary resources of copper and rare minerals. Government rhetoric on Foreign Aid and ongoing boundary negotiations, such as the Timore-Leste maritime agreement with Australia, grossly obscure and sustain the inequity inherent in these relationships. (8)

Records are not relics of the past, but direct veins between current political events and their inception. The trauma inscribed in archival collections is timeless; ‘wounds heal over on the body, but in the report they always stay open, they neither close up or disappear.’ (9)

ENDNOTES (all web resources accessed May 2017)

- Steedman, Carolyn. Dust (Manchester: Manchester Uni. Press, 2001) p.45

- University of Melbourne Archives collection can be explored by its 14 collection categories or by the occupation or activity of creators. See: The Catalogue ‘Browse’ search option. http://gallery.its.unimelb.edu.au/imu/imu.php?request=browse

- As the Commonwealth Department of Defence was located in Melbourne (1901-1958), it was logical that the Australian Red Cross National Office, which worked so closely with the Australian Imperial Force, was also located in Melbourne.

- http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/forever-in-chains-the-tragic-history-of-congo-6232383.html ; http://takingthelane.com/2011/10/25/the-rubber-terror-2/

- http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/German_New_Guinea ; http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-09-07/world-war-i-relatives-remember-gallantry-battle-bita-paka/5721738 and http://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/williams-william-george-billy-17327 (Papua New Guinea was colonised by both Britain and Germany – Australian government acting for the former. Australia’s administration was temporarily interrupted by the Japanese invasion (1942-1945))

- https://bougainvillenews.com/category/bougainville-copper/ ; http://www.ipsnews.net/2015/05/bougainville-former-war-torn-territory-still-wary-of-mining/ and https://thewellingtonchocolatevoyage.wordpress.com/ 2014/12/02/the-people-the-culture-the-land/

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/29/papua-new-guinea-apologises-bougainville-civil-war ; http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-05-04/bougainville-mine-moves-to-reopen-govermment-backing/8495496

- https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/07/is-your-cell-phone-fueling-civil-war-in-congo/241663/ ; https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/jan/14/aid-in-reverse-how-poor-countries-develop-rich-countries ; http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-01-09/east-timor-tears-up-oil-and-gas-treaty-with-australia/8170476

- Saramago, José: All the Names (New York: Harcourt, 1999) Translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa. p.66

UMA offers a comprehensive reference service advising clients who are engaged in complex topics. http://archives.unimelb.edu.au/information/for_researchers Some of the collections held at the University of Melbourne Archive which relate to Papua New Guinea & Bougainville, referred to in this blog, include:

AUSTRALIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY – NATIONAL OFFICE

PAPUA NEW GUINEA – DIVISION RECORDS, 1940-1972 (2016.0060)

PAPUA NEW GUINEA DIVISION NATIVE CHOIR, Gramophone Record (2016.0077)

VOLUNTARY AID DETACHMENT (VAD) AND FIELD FORCE PERSONNEL RECORDS (2016.0050)

MISSING, WOUNDED AND PRISONER OF WAR ENQUIRY CARDS (2016.0049)

EXECUTIVE CORRESPONDENCE (2015.0033)

INTERNATIONAL PROJECT FILES (2016.0057)

HUMANITARIAN ORGANISATIONS – CARE

FRASER, JOHN MALCOLM (multiple accessions) Chairman (1987-2002) CARE Australia and President of CARE International (1990-1995). See: Masters Elizabeth, Wood Katie (2012) Malcolm Fraser: guide to archives of Australia’s Prime ministers Canberra, National Archives of Australia and University of Melbourne Archives.

POLITICS – GOVERNMENT

FRASER, JOHN MALCOLM (multiple accessions) Army Minister (1966-1968) Minister for Defense (1969-1971) Prime Minister (1975-1983). Ibid

PAPUA NEW GUINEA PATROL OFFICERS – ORAL HISTORY TAPES (1999.0062) Australian government patrol officers acting on authority from the Papuan New Guinea government

ECOMOMISTS

ISAAC, JOSEPH EZRA (2009.0004) Consultant for the Department of External Territories (Canberra) and the Department of Labour (Port Moresby) on PNG labour problems (1969-1973)

LAW

MINOGUE, JOHN PATRICK Sir (multiple accessions) Circuit judge (1962-1969) of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Papua New Guinea, later Chief Justice (1970-1974)

DERHAM, DAVID PLUMLEY Sir (multiple accessions) Involved in constitutional reform of Papua New Guinea

BUSINESS – BANKING

JOHNS, JAMES HAROLD WESLEY (1972.0054) Established and managed a branch of the Bank of New South Wales in Salamoa, Papua New Guinea (1929-1932)

BUSINESS – MINING

BOUGAINVILLE COPPER LIMITED (1992.0008)

JOHN T RALPH (1997.0022) CRA Ltd., Managing Director

VERNON, D.C (1988.0086) Director of CRA and Chairman of Bougainville Copper Ltd.,

WOODWARD, OLIVER HOLMES (1978.0079) Diaries and accounts of OH Woodward’s mining trips to PNG with Colin Fraser, 1930s

BUSINESS – PLANTATIONS

B. RITCHIE & SON PTY. LTD. (1985.0083) Records relating to various family members involvement in business ventures including Garua Plantation in Papua New Guinea (1947-1951)

PERSONAL ACCOUNTS

WOODWARD, OLIVER HOLMES (1978.0079) Personal diary of Marjorie Moffat Wadell’s (later Woodward) trip to PNG, 1918.

MEDICAL

OSER, OSCAR ADOLPH (1985.0155)

CAMPBELL, BRIGADIER EDWARD FRANCIS (1999.0060)

WHITE, DAVID (2015.0088)