The eminently capable Mr Brown: Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and his magnificent tree moving machine

The Rare Books Collection contains vestiges of many intriguing characters from the worlds of history, science and literature. Amongst the colourful cast can be included the landscape gardener Lancelot Brown (1716-1783), whose 300th birthday is being celebrated this year. Both lauded and lampooned in his lifetime, Brown transformed 18th century English garden design, had an intense aversion to red brick (‘it puts the whole valley in a fever’), and invented an exceptionally effective tree moving machine.

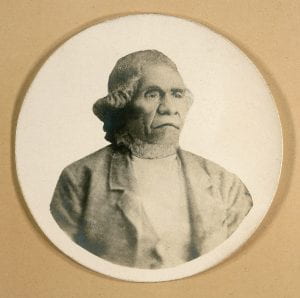

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

Born on the estate of Kirkhale Hall, Northumberland to a yeoman father and house maid, Brown is better known by his nickname of ‘Capability’, for assuring his aristocratic clients of the great potential, or ‘capability’, for realising improvements to their landed estates. Brown remodelled the spaces surrounding English stately homes into verdant sweeping landscapes, of a kind that could be appreciated from the ease of one’s carriage, or from vantage points picturesquely positioned in one’s grounds.

By account Brown was a swift worker and could assess and produce a plan within an hour of riding about an estate and soon found his services sought by the most fashionable and wealthy gentry of the day. This success was in part due to his ability to envision and design expansive gardens, but was underpinned by a particular capacity to translate theory into practice.

Trees and tree planting

One of Brown’s signature devices was the deft positioning of trees and copses and other arboreal plants to create ‘naturalistic’ effects in the landscape. Trees, however, take years to grow and planting is rarely the interest of younger generations. If Brown’s gardens were to mature in their owners’ lifetimes, then mature plantings were needed – his wealthy clientele simply couldn’t, or wouldn’t, wait the 30 or more years needed for an oak tree to attain a lofty height, or for a picturesque woodland feature to mature. One shortcut to achieving this instantaneous sylvan idyll was the technique of repositioning semi-mature and advanced trees in a new setting, as if they had grown there from seed.

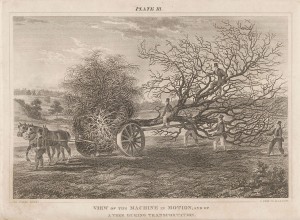

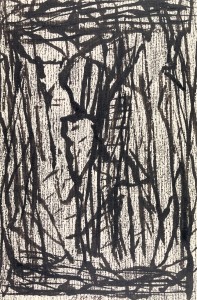

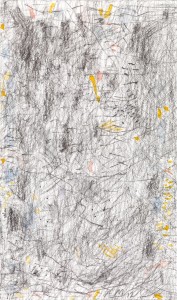

Methods for transplanting large trees had been devised before but it was an expensive and labour intensive activity, based on a tradition of moving the plants in an upright aspect, using a cumbersome combination of chains and pulleys. Brown was the first to understand the practical advantage of moving trees in a horizontal position and designed a simple but effective machine for this purpose. The machine, which served him well for the length of his career, was not only faster but enabled transplanting of advanced trees of between 15-36 feet relatively easily.

The Transplanting Machine

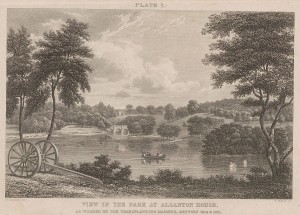

Writing 40 years after Brown’s death, Sir Henry Steuart, the author of The Planter’s guide…(1828) describes Brown’s ‘Transplanting Machine’ as it was used at Allanton House, Lanarkshire, Scotland:

‘It consists of a strong Pole and two Wheels, with a smaller wheel occasionally used, which is fixed at the extremity of the pole, and turns on a pivot. The pole operates both as a powerful lever, to bring down the Trees to the horizontal position, and in conjunction with the wheels, as a still more powerful conveyance, to remove them to their new situation’.

The roles of the various labourers involved in the transplanting operation were critical: the Machiner (who positioned the apparatus to receive the tree), the Steersman (who walked at the rear of the machine and managed the top of the tree), the Balancemen (two or more workers who scrambled on top of the horizontal tree and acted as movable counterweights), and the whole party supported by assistants who held ropes and walked at the side of the transplanting apparatus to help steady the moving specimen.

Occasionally things did not go to plan, such as when a tree unexpectedly took on the properties of a giant catapult:

‘In proceeding with the Machine down a gentle slope of some length, at an accelerated pace, on which occasion both the Balancemen had gained the top with their usual agility, it so fell out, that the cords, which secured the rack-pins of the root, unfortunately gave way. This happened so suddenly, that the root at once struck the ground, with a force equal to the united weight of the mass, and the momentum of the movement, and pitched the Balancemen (now suddenly lifted to an elevation of nearly thirty feet), like two shuttle-cocks, to many yards’ distance, over the heads of the horses and the driver, who stood in amazement at their sudden and aerial flight! Luckily for the men, there was no frost upon the ground, so that, instead of breaking their bones, they fell only on the soft turf of the park; from which soon getting up and shaking themselves, they heartily joined in the laughter of their companions, at the extraordinary length of the leap which they had taken’.

Apparently, despite the collective mirth, it ‘proved impossible’ to coerce the Balancemen ‘to resume their elevated functions, for many months after’…

Susan Thomas, Rare Books Curator

Bibliography and further reading from the Rare Books Collection

Bibliography and further reading from the Rare Books Collection

All quotes and images are taken from Henry Stueart’s The Planters guide…(1828)

Cradock, Joseph. Village memoirs: in a series of letters between a clergyman and his family in the country, and his son in town. Dublin : Printed for P. Wilson, Skinner-Row; and M. Mills, Capel-Street, 1775.

Goldsmith, Oliver. The traveller, The deserted village, and other poems. London : Printed for John Sharpe…by C. Whittingham, 1819.

Hinde, Thomas. Capability Brown: the story of a master gardener. London : Hutchinson, 1986.

Neale, John Preston. Views of the seats of noblemen and gentlemen, in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland / from drawings by J. P. Neale. London : Published for W.H. Reid, 1818-1823.

Steuart, Henry. The Planter’s guide: or, a practical essay on the best method of giving immediate effect to wood by the removal of large trees and underwood… 2nd edition. Edinburgh : John Murray, 1828.

Walpole, Henry. The history of the modern taste in gardening. New York : Ursus Press, c1995.