Shakespeare in Steel: exploring links between Edward Dowden’s ‘Shakespeare Scenes & Characters’ and the ‘Gallerie Shakespeare’ portfolio of engravings. Part II.

On the 15th July 2016, the University of Melbourne’s highly anticipated After Shakespeare exhibition was officially opened, in the Noel Shaw Gallery of the Baillieu Library. Marking the 400th anniversary of the year of the Bard’s death, the exhibition plays host to a number of artefacts and ephemera that highlight Shakespeare’s lasting legacy throughout the centuries, with particular focus on his reception in Australia.

On the 15th July 2016, the University of Melbourne’s highly anticipated After Shakespeare exhibition was officially opened, in the Noel Shaw Gallery of the Baillieu Library. Marking the 400th anniversary of the year of the Bard’s death, the exhibition plays host to a number of artefacts and ephemera that highlight Shakespeare’s lasting legacy throughout the centuries, with particular focus on his reception in Australia.

Amongst the intriguing stories contained in the cases is a puzzling connection between an 1876 English book of Shakespearian commentaries and engravings, and a separately issued portfolio of 22 engravings with a French title. Helen Kesarios, a student volunteer in the Cultural Collections Projects Program, has been investigating possible connections between the two works, drawing on original correspondence located at the British Library.

Part I told the story of the Shakespearian scholar, Edward Dowden, and the publication of his exquisitely illustrated text, Shakespeare Scenes & Characters (London : Macmillan and Co, 1876).

The second instalment in this three-part story continues here…

Part II – The German engravings: Shakespeare Scenes & Characters selected and arranged by Edward Dowden

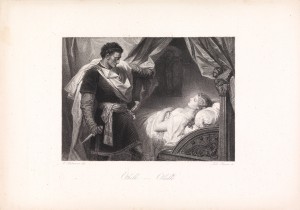

Despite Dowden’s intentions that the criticism and images be appreciated as a whole, the interest of readers often focuses on the latter. As Kathryn R. Ludwigson notes:

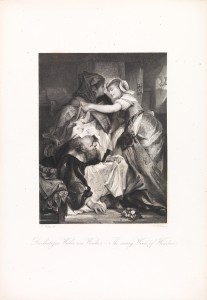

‘The book is unusually interesting not so much for Dowden’s presentations of Shakespearean criticism, which are, after all, available more fully elsewhere, as for the collection of German engravings, which are governed by concepts of art that contrast with those of the English of the era’.[i]

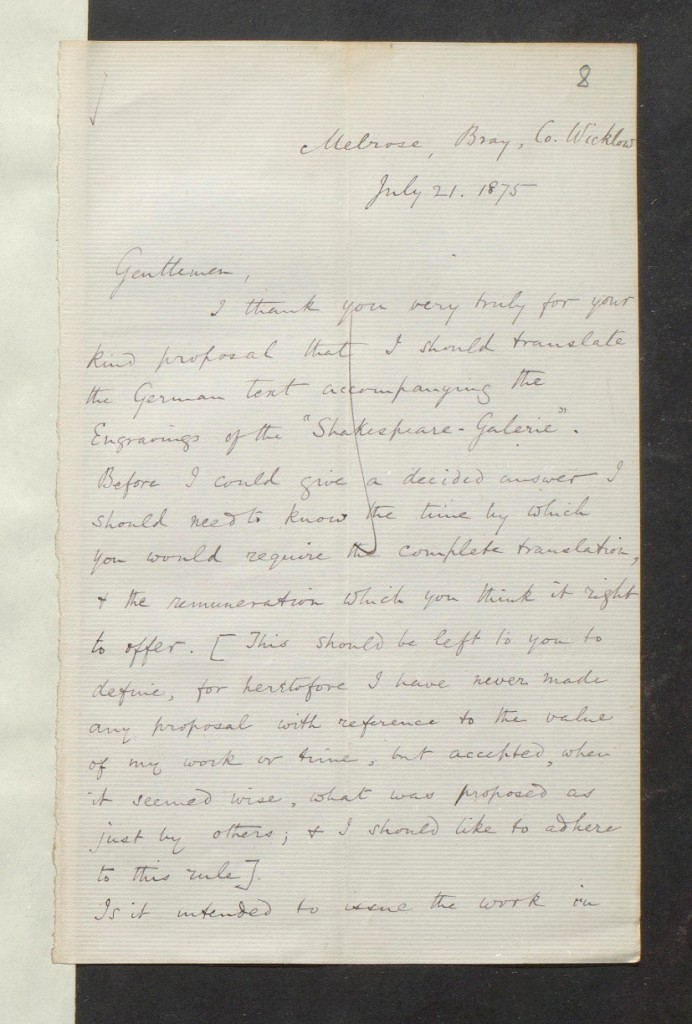

Given that steel engraving was already a well-established art form in Great Britain, it is important to consider some of the factors which might have influenced Dowden to choose German artists and engravers over English ones for his book. Perhaps the most striking piece of evidence is contained in the opening to the Preface, where Dowden pays homage to ‘Germany, which has so largely contributed to the scholarly study of Shakespeare, [and which] has also made some remarkable contributions to the pictorial illustration of his plays’.[ii] Dowden was no stranger to German criticism of Shakespeare having, after all, included German criticism in the text, (the works of Friedrich Pecht in particular). He also notes his studying endeavours in a letter to Aubrey de Vere on March 6th, 1875:

‘These miscellaneous little activities of mine are: (1) An article for the Fortnightly Review, to be by-and-by written on “Wordsworth’s Prose Works.” (2) The Quarterly Review on “German Shakespeare Literature”…’[iii]

It is also worth noting that the relationship between Germany and Shakespeare is an historic one, and its significance is embodied in the sentiments of German romantic writers such as Goethe (of whom Dowden was particularly fond), who saw in Shakespeare a revolutionary mascot of the times:

‘These authors rebelled against the bureaucracy and despotism of the German states, particularly Prussia; and against the passivity and optimistic contentment of the earlier generation…these “intellectuals”, members of the professional class, applied themselves to an intellectual revolution, a war of liberation of the senses, feeling, imagination. Shakespeare became their most challenging and inspiring slogan…on reading Shakespeare [Goethe] feels his “Existenz erweitert”; Shakespeare, he says, illustrates always the struggle between our presumed freedom of will and the necessary process of the world. For all these writers Shakespeare offered a world of vast activity and experience, in which they felt themselves transported beyond the barriers and restrictions of contemporary German life’.[iv]

In terms of the prints’ aesthetic value, Dowden writes in a letter to Macmillan and Co. on July 21st, 1875, that ‘the illustrations are in part interesting to me as a German art-comment on, or interpretation of Shakespeare, and each has made me feel something new about the play to which it belongs’. They were generally well received by the public, with critics noting the skill employed by the German artists and engravers in executing each design:

‘As a whole the series of pictorial illustrations of Shakespearean scenes is strikingly good. Some of the designs are too Teutonic in character, perhaps, but commonly the artist has been successful in the interpretation of character and incident… “The Merry Wives of Windsor”…is one of the best in the series, the artist having caught the individuality of the actors and the spirit of the incident with decided success…Taken as a whole, as we have said, it is an excellent Shakespearean gallery, and shows that German artists are not inferior to German scholars in Shakespearean lore’.[v]

If the reader wishes to know more about each featured artist, Dowden provides a brief ‘curriculum vitae’ in the Preface.

Helen Kesarios

Research Assistant, After Shakespeare exhibition

Cultural Collections Project Program, University of Melbourne

HELEN KESARIOS WILL CONCLUDE THE STORY OF THE ENGRAVINGS CONTAINED WITHIN THE DOWDEN VOLUME IN HER FINAL INSTALMENT NEXT WEEK.

WATCH THIS SPACE FOR PART III – The French portfolio of German engravings

[i] Kathryn R. Ludwigson, Edward Dowden, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1973, p. 28.

[ii] Dowden, Shakespeare Scenes and Characters, p. v.

[iii] Dowden, Letters of Edward Dowden and his Correspondents, p. 72.

[iv] R. Pascal, Shakespeare in Germany: 1740-1815, Cambridge University Press, London, 1937, p. 12.

[v] Brooklyn Museum, ‘Recent Art Publications’, The Art Journal 1875-1887), vol. 3, 1877, p. 31.