Thousands of sea miles and water as metaphor

My love for the sea is so strong that life feels to me only half-lived on land. 1

Images of water and maritime culture are strong themes in Percy Grainger’s art collection. John Harry Grainger, Percy’s father, was an architect and a fine watercolour painter who produced seascapes and maritime scenes for pleasure. The paintings he gifted his son demonstrate an innate understanding of the tensions and energies that combine to create wind-powered sea travel—an interest he passed on to his child. He was his son’s first art teacher. Among Percy Grainger’s juvenilia are numerous paintings and drawings of watercraft.

John Harry Grainger (1854-1917), French fishing boats entering Boulogne harbour, 1892. Watercolour on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

It is easy to comprehend Grainger’s love of maritime imagery. As a touring concert pianist he spent many thousands of hours at sea, starting his lifetime of sea voyages when he sailed from Australia at the age of 13 to take up his formal studies in music in Frankfurt.

Three years after graduation he was touring South Africa and Australasia with the renowned Australian contralto, Ada Crossley—again, covering many sea miles—and he joined a second tour with her four years later.

Grainger became an obsessive tall ship enthusiast. As a child he experienced the last days of sailing cargo vessels undertaking coastal trade in Australia. He also saw windjammers docking in Melbourne and made sketches of these vessels, as well as their steam-powered competitors.

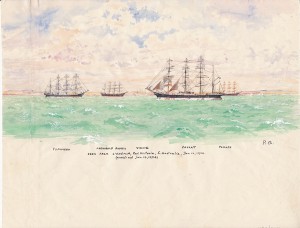

At 51, Grainger had an opportunity to experience what would have been a dream to lovers of square-rigged ships. He and his wife Ella spent 101 days on a sea voyage to Australia (1933/34) on the Finnish Barque, L’Avenir. It was a profound experience for him, which he recorded in paintings and drawings. He made visual notes of passing ships, landscape profiles from the sea and the minutiae of deck and rigging structures. He later had a scale model of the vessel fabricated.

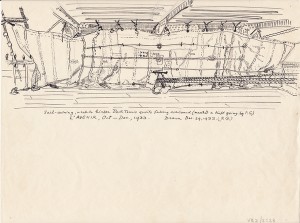

Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882-1961), Sail-awning, used to hinder deck tennis quoits falling overboard (mended and kept going by P.G.). L’Avenir, December 1933. Ink on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882-1961), Pomern, Archibald Russell, Viking, Passat and Ponape, seen from L’Avenir, Port Victoria, S. Australia, January 1934. Watercolour on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

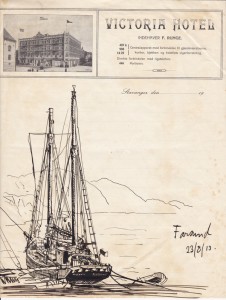

Grainger painted and sketched throughout his life. The deftly drawn pen and ink of a two mast sailing vessel in port at Farsund in Norway was executed on Hotel letterhead—another example of Grainger’s habit of visual note making as he travelled.

Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882-1961), Farsund, 23 August 1913. Ink on letterhead. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

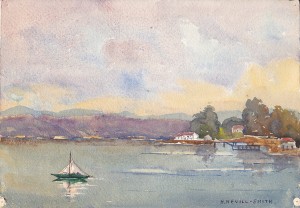

For a man who documented his life with extraordinarily copious notes, there is limited provenance to some of the works in the exhibition Water, marks and countenances: works on paper from the Grainger Museum collection . Little is recorded of the Californian watercolourist, Hugh Nevill-Smith, whose confidently executed seascape is on display.

Hugh Nevill-Smith, Sailboat on a lake, n.d. Watercolour on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

The crisp etching of Strandvägen and Nordic Museum (in Sweden) signed ‘Knorr’ may have been by a relation of Grainger’s Frankfurt composition lecturer, Iwan Knorr. And whether Grainger met the New Zealand artist, Cranleigh Barton, is unknown. The artist’s watercolour of London Bridge is a spare, luminous image in the impressionist style.

Cranleigh Harper Barton, London Bridge, n.d. Watercolour on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

By contrast, some of the works are by friends and were gifted to Grainger. Flora M. Pilkington, known for her watercolours of gardens, produced an image of Edvard Greig’s lakeside home, Troldhaugen, in the year of the composer’s death. Eight years later she gave it to Grainger with a note telling him of the difficulties of finding an appropriate view point.

Flora M. Pilkington, Autumn sketch at Troldhaugen, c.1907. Watercolour on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

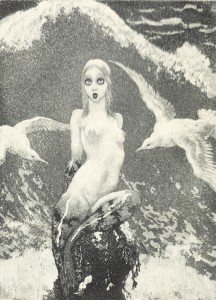

Old junks in Shanghai harbour is by Grainger’s friend and early mentor, Mortimer Menpes. Norman Lindsay’s Little Mermaid and his melange of nudes (in and out of water), boats, castles and sheep dogs, titled Capriccio, are two works from a small group of prints Lindsay gave Grainger. As well as sharing a love of erotica, the two artists were fond of model ships.

Norman Lindsay (1879-1969), The little mermaid, 1934. Etching and aquatint on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

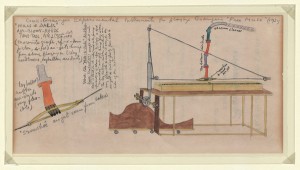

The inclusion of detailed watercolours of Grainger’s experimental music-making machines in the exhibition has a less obvious, yet still pertinent connection with the theme of water— here water is metaphor.

Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882-1961), “Hills and dales” air-blown-reeds tone-tool no.2 (snowshoe), October 1951. Watercolour, ink and graphite on paper. Grainger Museum collection, University of Melbourne

The last musical adventure of Grainger’s life was his experimental ‘Free Music’. He likened the new sonic forms he was generating to the movement of water. His vision was of a music unconstrained by western conventions of pitch and rhythm. Gone would be the incremental movements of melody, harmony and rhythm. The sounds in his head were of gliding tones or Glissandi, and irregular rhythms: multiple voices threading through each other like the lapping of waves breaking on the side of a moving boat.

My impression is that this world of tonal freedom was suggested to me by wave movements in the sea that I first observed as a young child at Brighton, Victoria, and Albert Park, Melbourne.2

By Brian Allison

Exhibitions Coordinator, Special Collections and Grainger Museum

Footnotes:

- Percy Grainger to Douglas Charles (D.C.) Parker, 28 August, 1916

- Percy Grainger, ‘Free Music 1938’, in Gillies and Clunies Ross, Grainger on Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999