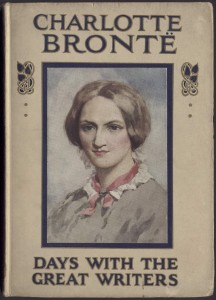

Reading with the young Charlotte: celebrating the 200th birthday of Charlotte Brontë with some books from an unconventional childhood

This month marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charlotte Brontë, the third-born and longest lived of the six children of Patrick and Maria Brontë, and the author of the classic novels Jane Eyre (1847), Shirley (1849), Villette (1853) and The Professor (1857). Much has been written about Charlotte and her famous 19th century literary family, and the mystique of their lives and legacy has been the subject of continuing interpretation and reinterpretation. The Baillieu Library is very fortunate to hold some important early Brontë editions, together with copies of several titles which they are known to have read, if not devoured, as children.

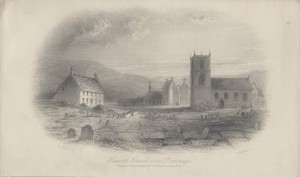

The timeworn autobiographical themes of the Brontë story are familiar to most readers of English literature: the isolated parsonage on the edge of the Yorkshire moor; the bleak childhoods of Charlotte, Emily and Anne, overshadowed by the premature death of their mother and two elder sisters, and misfortunes of brother Branwell; and the untimely deaths of Emily and Anne by the age of 30, and Charlotte at 38. Like most legends, the Brontë one is part myth, part truth, and it seems that despite their many adversities, the Brontë home was a warm and happy one, and Haworth was a small bustling town, where the Brontës lived in a manner that was no worse, and often better, than their neighbours.

An unconventional childhood and the Brontë’s book interests

Less prominent in the popular imagination, and what set the young family apart from their village counterparts, was the children’s unconventional upbringing and education. A precocious curiosity was encouraged by their Rousseau-like father, Reverend Patrick Brontë, who had taken up the perpetual curacy of St Michael and All Angels’ Church in 1820. A Cambridge-educated scholar from a poor Irish background, Patrick included his children in adult conversations and his business affairs and encouraged them to read and discuss the books, journals and newspapers which he added to his library [1]. The children consumed omnivorously, the only recorded restriction to their literary diet being the popular gossipy women’s paper, the Lady’s Magazine; or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex (1770-1847), as it contained ‘foolish love stories’ [2].

A glimpse of the parsonage bookshelves is provided by Charlotte’s first biographer, Elizabeth Gaskell:

‘the well-bound were ranged in the sanctuary of Mr B’s study…up and down [the house] were to be found many standard works of a standard kind’. These were supplemented by some books from Maria Brontë’s side of the family – ‘mad Methodist Magazines full of miracles and apparitions…preternatural warnings, ominous dreams, and frenzied fanaticism; and the equally mad letters of Mrs Elizabeth Rowe, the popular 18th century author of Friendship in Death (1728)’ [3].

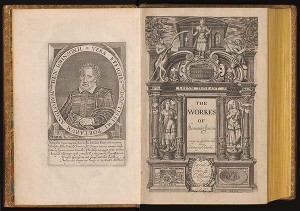

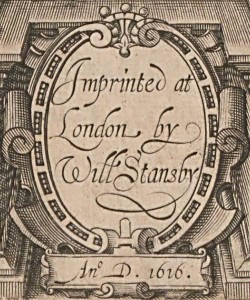

Some of the children’s favourites included natural history and geographical works – Bewick’s Book of Birds (1804),The Garden and Menagerie of the Zoological Society (1831), and Goldsmith’s Grammar of General Geography (1819), copies of all of which can be found in the Baillieu’s Rare Book Collection. Their young imaginations were stirred by stories of The Arabian Knights (1706), the Romantic works of Sir Walter Scott, Lord Byron, and John Bunyan, and a volume containing dramatic scenes by engraver John Martin (1789-1954).

Reverend Brontë subscribed to several journals including the Leeds Intelligencer, Blackwood’s Magazine and Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, all of which contained news and articles on contemporary events, people and places [4]. These were as an important influence on the children as the fictional stories that they read, with the children absorbing ‘information from every possible source, devouring newspapers, magazines, annuals, children’s books and their father’s library for their source material for their own creations’ [5].

Imaginative influences and first writings

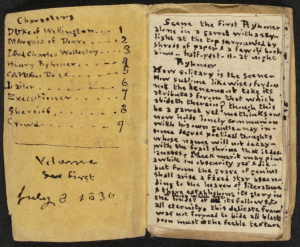

This rich literary environment provided inspiration for the young Brontës’ games, which became further animated when brother Branwell was given a set of toy soldiers as a gift from his father. Sharing the soldiers with his sisters, the children began writing scripts of adventure, mimicking the adult publishing world in a series of tiny hand-manufactured books. Charlotte’s first book was written in 1824 when she was nine as a present to her younger sister Anne. It took the form of a manuscript about the size of a matchbox and penned in minuscule handwriting, now preserved with several other examples in the Brontë Museum in Haworth. Other examples of Brontë juvenilia are held by the Houghton Library (Yale University), the British Library and the Musée des Lettres et Manuscrits in Paris.

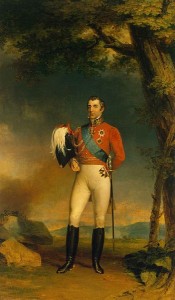

Prominent amongst Charlotte’s childhood heroes was the Duke of Wellington, a passion she shared with her father Patrick Brontë, and she named her toy soldier after him. The Blackwood’s reports in turn provided models for many of her juvenile stories, infusing a cast of ‘important aristocratic figures engaged in struggles over power…with the addition of many tangled love affairs’ [6]. One story involved an attempted poisoning, and in another his sons, Arthur and Charles were the subject of a bid to kidnap them.

On 200th anniversary of Charlotte Brontë’s birthday it is intriguing to pause and reflect on the many books which fostered her highly imaginative inner life as a child. By revisiting this rich source material, modern researchers can continue to obtain privileged insights into the early influences and lasting literary legacy of this gifted writer and those of her remarkable family.

Susan Thomas (Rare Books Curator)

Endnotes

[1] Wilks, B. The Brontës: an illustrated biography. New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1986, p. 63

[2] Ingham, P. The Brontës. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 70

[3] Elizabeth Gaskell in Lane, M. The Brontë story. [London]: Fontana, 1973, pp. 108-109

[4] Ingham, P. Op cit, p. 72.

[5] Wilks, B. Op cit, p. 54

[6] Ingham, Op cit, p. 72

Interested in learning more?

- Visit the Brontë Society (UK) website at https://www.Brontë.org.uk/about-us or the Australian sister-society at http://maths.mq.edu.au/~chris/Brontë/

- Read more about Charlotte and the British Library’s Brontë collections at http://www.bl.uk/people/charlotte-Brontë#

- Visit the Houghton Library website for examples of Brontë juvenilia http://hcl.harvard.edu/libraries/houghton/collections/modern/british_irish_collections.cfm

Select bibliography

Bentley, P. The Brontës. London: Pan, 1973.

Hughes, G. ‘The Brontës and Yorkshire’ in The Oxford guide to literary Britain & Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 233-234.

Ingham, P. The Brontës. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Lane, M. The Brontë story. [London]: Fontana, 1973.

Wilks, B. The Brontës: an illustrated biography. New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1986.

Wollaston, E. Little book of the Brontë sisters. [Swindon], UK: Green Umbrella, 2008.