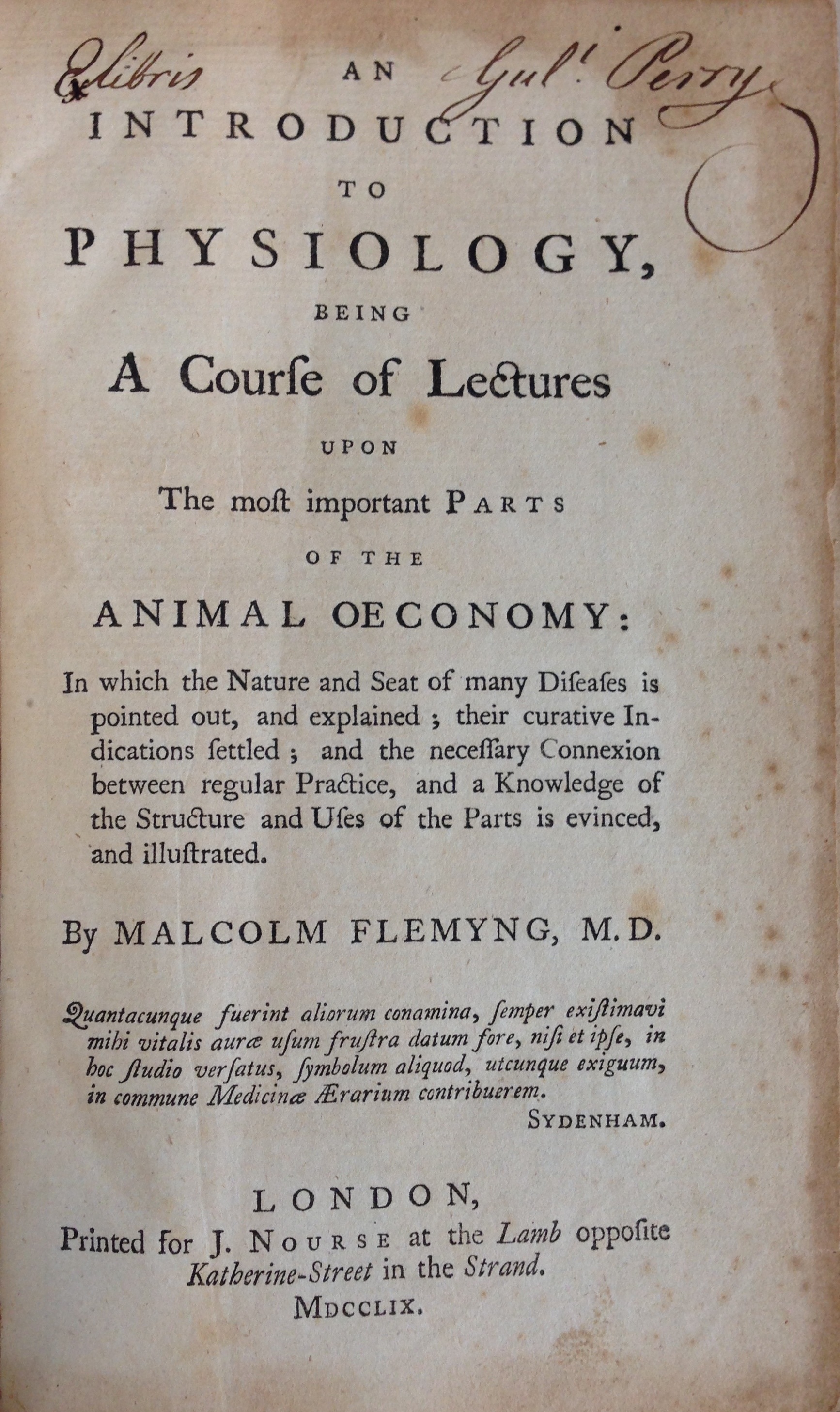

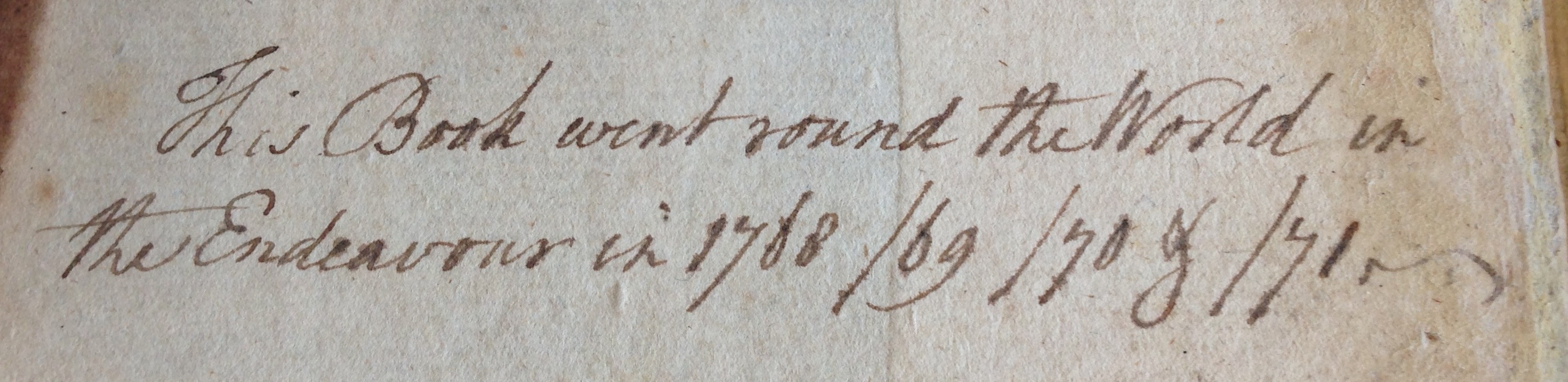

Saint Paul shipwrecked in the Noel Shaw Gallery

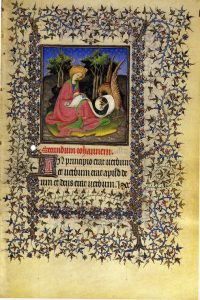

One of the more creative themes in the current exhibition in the Noel Shaw Gallery Plotting the island: dreams, discovery and disaster, relates to St Paul on Malta. When the exhibition was under development, I was interested to include objects which represented both the classical and biblical inspirations for the voyages of exploration which launched through the 15th to 18th centuries.

The Prophet Paul’s story features a shipwreck that occurred in the Mediterranean. Shipwrecks are one of the dramatic subjects in the exhibition, and St Paul is well-represented in the Print Collection, thus the availability of visual documents was one of the several reasons to include it. A snippet of information I read in passing, suggested that the earliest recorded shipwreck is found in the Old Testament. The validity of this idea and its correlating obscure wreck was superseded in the exhibition by the intriguing narrative in the New Testament account by Luke in the Book of Acts.

Approximately 2000 years ago, Paul was being transported as a prisoner to Rome aboard a grain freighter, when the ship was engulfed in a spectacular and violent storm which caused it to run aground and wreck on Malta.

The group of 276 sodden and wretched shipwreck survivors are poignantly depicted with almost individual detail in Jan Luyken’s etching, where they are being helped by islanders to build a fire. This image proved to be the main, and a very powerful visual experience of shipwreck for the exhibition, particularly in lieu of an image for the extraordinary Dutch shipwreck Batavia which is instead expressed through a contemporary handwritten music score from the Rare Music Collection. [1] The etching is seen through a Dutch lens as it was published in a Dutch Bible in 1729 (Historie des Nieuwen Testaments).

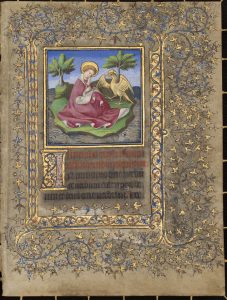

After emerging from the sea, Paul gathers firewood, which contains a poisonous viper that, when driven out by the heat, latches onto his hand. Paul’s unaffectedness to the deadly bite was one of the miracles that led to his apostleship. The scene is dramatically depicted in St Paul (1790). This print is after the original painting by Benjamin West, commissioned by the directors of Greenwich Hospital and is now part of the National Maritime Museum in London.

The biblical describes four anchors that were cast into the sea during the storm. It is hard to imagine how objects designed to be thrown overboard could have survived through time, yet ancient anchors have been found by archaeologists. I am frequently inspired by the objects which may be unearthed from the University’s collections, and am somewhat awed to be able to include an anchor, similar in origin, age and usage to that described in the Bible, in Plotting the island.

Although it has been described as a ‘Maltese anchor’ the anchor is instead Roman in origin and was excavated from a Roman wreck at Xlendi, a bay found on the island Gozo, off Malta. [2.] The anchor provides insight into Roman-occupied Malta and its maritime activity. The anchor is made of lead and very heavy – as the exhibition team was to discover. It is too heavy for one person to lift and required extra help to transport it from the Ian Potter Museum of Art where it resides. [3.] All up, six people were involved to place it on its specially made support and into the showcase during the exhibition installation.

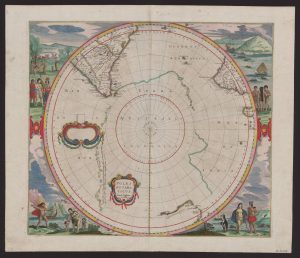

The island Gozo is also the legendary home of the sorceress Calypso (Circe) in Homer’s Odyssey, which is also touched upon in the exhibition. These landmasses may be located in Jacob Sandrart’s map, Nova totius Graeciae, Italiae, Natoliae, Hungariae nec non Danubii fluminis … (New map of the whole of Greece, Italy, Anatolia, Hungary and the Danube River …) (c.1660).

The trials of shipwreck are a fascinating aspect of the exhibition, but just as beguiling is being drawn into mysterious bays and inlets, like those found on Malta, to discover cultural treasures.

Kerrianne Stone (Curator, Prints)

References

[1.] Batavia [music] by Richard Mills; libretto, Peter Goldsworthy

[2.] Claudia Sagona, The archaeology of Malta: from the Neolithic through the Roman period, New York, NY Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 283

[3.] The Huber Collection of Maltese Antiquities