The “Brawny Farmer from Dubbo” turned International Boxer

Alexia Rutkowski

In the digitised images of the Stadiums Pty Ltd archive collection, Australian boxer, George Cook caught my attention as several photographs included portraits with his wife and daughter, Julie, therefore, relating to his personal life as well as his boxing career. Intrigued to learn more about George, I questioned how a man from Cobbora, Dubbo, New South Wales could have a successful international boxing career during the 1920s and 1930s. Matthew Taylor explores how boxers in the 1920s and 1930s became “transnational icons” as sporting labour became incorporated into global networks and provided motivations for migration from the mid-nineteenth century onwards (Taylor, 2014, p.171). After World War I (1914-1918), there were also improved transportation and communication services which helped form international competitions, causing a new transnational sporting arena during the inter-war years (Taylor, 2014). These factors enabled George to compete internationally as a boxer.

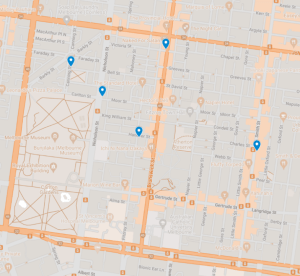

Born in Cobbora, New South Wales, Australia, on January 23, 1898. According to Boxer List, a database of title fights, George’s boxing career started on July 17, 1917, as he lost to Jim Tracey at Sydney Stadium. George’s last match took place in London at The Ring on Blackfriars Road on December 18, 1938. His career spanned twenty-years, and he boxed in Australia, America, Britain, and even in Europe. During international travel, boxers relied on journalists to share their experiences abroad through local and national newspapers, and updates on George’s career, in his matches and travel movements, can be traced through local Australian newspapers found in Trove, the National Library of Australia online search engine (Taylor, 2014).

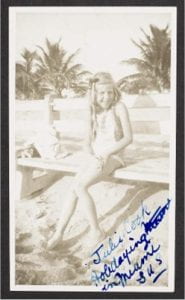

Overall, George won 43 matches, lost 50, and drew 10 (BoxerList, 2023). The first image in the University of Melbourne collection that alludes to George’s international boxing career is however a photograph of his daughter, Julie, on a Miami beach.

While the photo is undated, and Julie’s age is unknown, other articles confirm that George was in Miami in February 1930. “Serving as a sparring partner” to Jack Sharkey, an American heavyweight boxer (“Boxing”, 1930). George reports to The Northern Miner and Sunraysia Daily, that he did not enjoy sparring with Jack as he had been “treating him rough”. Despite the family portraits suggesting George had an international boxing career which started in America, George started his international career with three title fights in New Zealand where he was acclaimed as the ‘brawny farmer’ from Dubbo, and then sailed to Britain on the Orsova. Arriving in Britain in early 1921, George met his wife, and an issue of British Pathé on April 27 1922 includes a short video reel with the caption: “Australia’s Champion Heavy Weight boxer and his bride pose for the Pathé Gazette”. From the video, we also learn that George, was living in London and that by 1922, he had a significant reputation as a heavy weight champion boxer with an international career. Furthermore, a newspaper article from April 19, 1922 in the Geraldton Express stated that George was soon to marry a Mrs. Rider a war widow, in London, who he met at a dance. Wed between April 19 and April 27, 1922, George’s marriage to a British woman and his career in Britain, could explain why he decided to permanently reside in Britain as opposed to moving back to Australia. Another publication by Taylor documents that many international boxers settled in London or surrounding areas as it became the ‘capital’ of the boxing world in the mid-twentieth century (Taylor, 2009).

In February 1937, with little explanation, it was however announced by the British Boxing Board of Control that George needed to retire. After his retirement, Britain declared war on Germany, and George claimed, “I am too old to be a soldier, but nobody is too old to fight fires” (“George Cook, Former Heavyweight Boxer”, 1943). George passed away on October 8, 1943, in Surbiton, Surrey. The Burnie Gazette reported that George died from a short illness, and that in his retirement he was a member of the National Fire Service. At his time of death, George’s investments in Britain included a public house, café, and a snack bar.

To trace George’s travel movements in this blog post throughout his boxing career, you can follow this story map: https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/779c576b5c70d0218a17b0f004743d92/the-international-boxing-career-of-george-cook/index.html.

Alexia Rutkowski is a PhD candidate in the Asia Institute at the University of Melbourne. She is undertaking research on the history of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, focusing on transnationalism and the role of individuals.

References

Taylor, M. (2009). Round the London Ring: Boxing, Class and Community in Interwar London. The London Journal 34(2), 167-170. http://doi.org/10/1179/174963209X442432.

Taylor M. (2014). The Transatlantic Migration of Sporting Labour, 1920-1939. Labour History Review 79(2). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/228187215.pdf.