War and Peace: Stories of endeavour from the Australian Red Cross Collection

Chelsea Harris

Public Programs and Audience Engagement, University of Melbourne Archives

Within the University of Melbourne Archives’ 20 kilometres of records sits a relatively new acquisition, some 347 linear meters of records of the Australia Red Cross. Comprising 1,405 boxes across 36 series, these records relate to both the National Office as well as the Victorian Division (1914-2015) and include: Annual Reports and Financial Statements published by the National Office, Minutes of Annual General Meetings, Missing Prisoner of War cards, volumes of correspondence, newsletters and other publications, media releases and press clippings among other items. For much of the twentieth century the state Divisions of the Red Cross held primary responsibility for the delivery of Red Cross services, especially during peacetime, including blood transfusion services, tracing missing persons, hospital and convalescence, fundraising, disaster relief and a wide range of other community services.

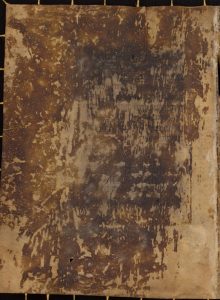

Among the bureaucratic records of a large organisation there lie the small but selfless feats of ordinary men, and in this case more often women, in the face of overwhelmingly difficult circumstances. One such item comes in the form of a large leather book: the Influenza Temporary Hospitals Staffing Register. This register served as a bureaucratic tool to record the temporary hospitals established across Melbourne to cope with the city’s Influenza epidemic from January – March 1919, introduced to the country by large numbers of returning soldiers. Within its pages a long list of hospitals can be found, (Camberwell Temporary Hospital, Oakleigh Temporary, Prahran Temporary, St Vincent de Paul Orphanage, Sandringham Temporary, Studley Hall Kew) among which I recognise the name of my own suburb, Brunswick, which was staffed by 23 Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD’s), trained nurses and volunteers. Among these women were several who “did not report for duty”, “declined to carry out instructions” and the case of one woman whose service was “withdrawn by mother”, perhaps because she was badly needed at home.

Accounts of the actual death toll differ, however most sources agree that around 10,000 people died in Australia during the Influenza Epidemic in 1919. In January, Victoria was declared infected and the state placed in quarantine with theatres and schools forced to close. Masked residents went about their daily business of shopping, attending church and using public transport while the New South Wales government closed the border with Victoria, prohibiting traffic between the states. The tiny cursive handwriting of the Influenza Temporary Hospitals Staffing Register’s author reveals somber details of quarantined houses, to which VADs and trained nurses were dispatched: “father came to office in a desperate way saying the doctor refused to go near the patients (his wife and two children)”, “father, mother and two children taken to the hospital – 4 of 5 children left in the care of a boy of 17 years”, “mother and four children ill, no food in the house, things in a deplorable condition”.

With their own health at risk, the VAD’s and others, including University medical students who assisted with the epidemic, showed tremendous fortitude, particularly those who had served at the front during the First World War. A Red Cross Record Knitting Booklet (New South Wales) represents another huge civilian effort coordinated by the Red Cross: to produce enough warm clothing for men and women serving at the front in the second world war. Within the booklet a wistful and well groomed man models a Waistcoat Muffler, an item that would have been knitted by some of the large numbers of women who became members of the Red Cross. Knitting was an activity that could be done alone or in groups (and not only by women) and this very useful task contributed to a staggering volume of garments put to good use in the days before synthetic fabrics.

Tucked in manila folders within the pale grey boxes of Junior Red Cross records are colourful booklets which served to educate children on healthy eating, providing basic first aid, how to knit their own Australian Red Cross Cape and even create their own library. Shaping productive, selfless and active citizens of the future was one of the primary aims of the Australian Junior Red Cross. Founded in New South Wales in August 1914, the organisation originally aimed at involving children in supporting recuperating soldiers. The first movements in Canada and Australia moved from a focus on improving health, preventing disease and mitigating suffering, to one on personal health, citizenship and service, and international friendship. The Junior Red Cross Health Game (1947) with its simply drawn figures brushing their teeth, drinking their recommended 3 cups of milk a day and breathing through their nose (!) is one such instructive example of this focus on health, particularly after a period of wartime deprivations. Similarly, a Junior Red Cross First Aid booklet full of quirky illustrations shows children how to help heal a toothache, deal with a burn or stem the flow of a bloody nose.

The thread that runs through and connects these stories within the Australian Red Cross Collection is one of community-minded individual endeavour; whether knitting socks for the front, playing a game of good health, or risking your own to care for others infected with a deadly virus. The bureaucratic records speak to the massive scale of its operations as one of the oldest and most respected voluntary organisations in Australia, yet for me the items that highlight individual feats, quietly undertaken, speak the loudest as to the humanity that the Red Cross seeks to celebrate.

The Collection is open to all researchers and can be accessed through our website.

All images are reproduced for study and research purposes only.

Many thanks to my colleague Stella Marr for her assistance in sourcing content for this blog post and her insights and knowledge into this collection.