Centenary of Japanese language teaching at the University of Melbourne

In early 1917, the call for Instructors of the Russian and Japanese languages at the University of Melbourne was advertised in several Victorian newspapers. The roles were not salaried, but instead paid a portion of student tuition fees. An Instructor of Russian was appointed; however, it was not until the following year that a suitable arrangement for the teaching of Japanese gained support.

In August 1918, a report to Council by the Faculty of Arts outlines the practical concerns about teaching a ‘Pacific’ language at the time, and a solution; that two instructors each with differing but complementary strengths be employed. The Faculty recommended that Senkichi ‘Mowsey’ Inagaki and the Reverend Thomas Jollie Smith become the first teachers of Japanese language teaching at the University of Melbourne. Smith was to be appointed as Instructor of Japanese language, with Inagaki as Assistant Instructor.

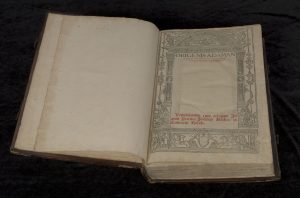

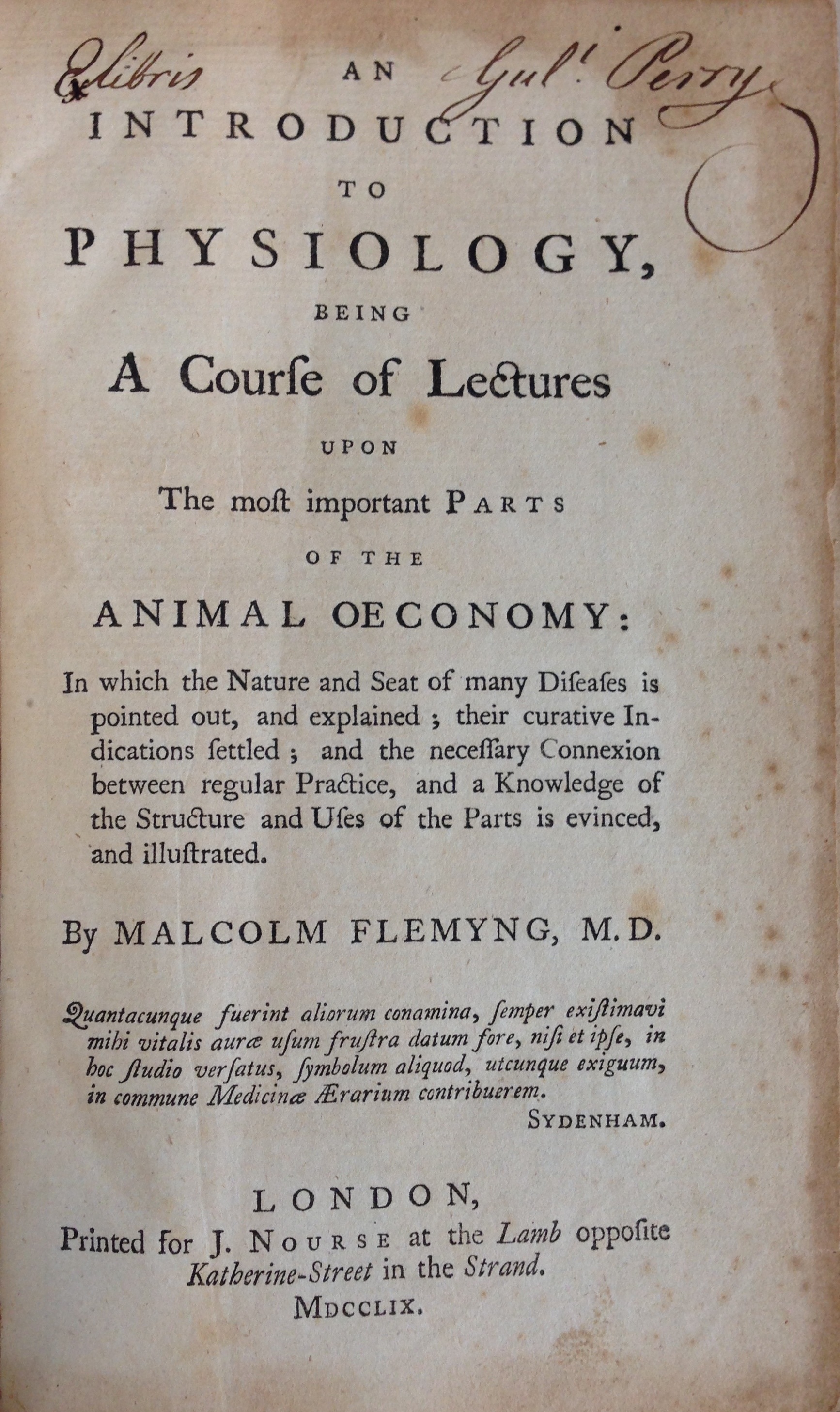

Title-page with Perry’s ownership inscription.

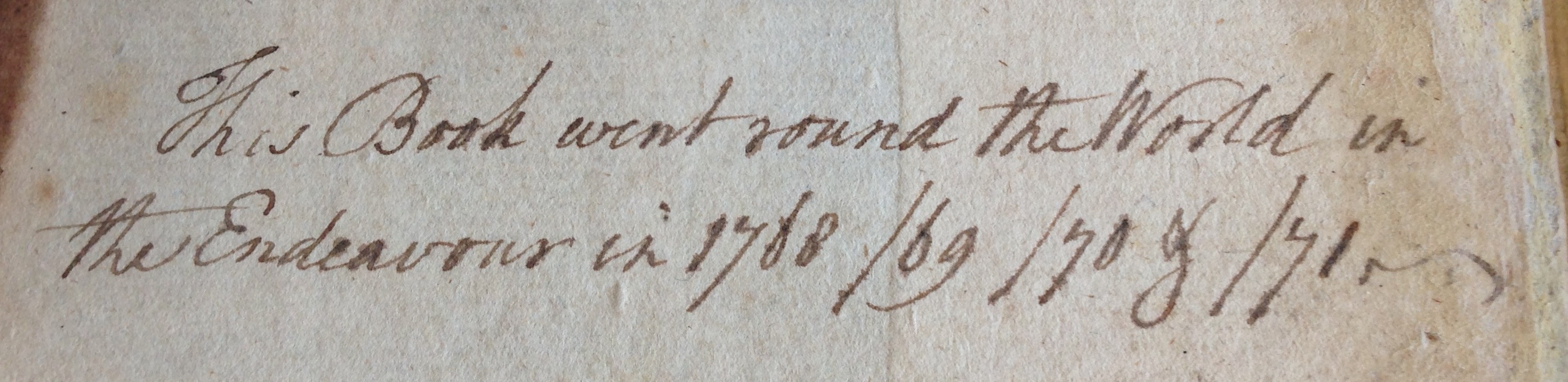

‘This Book went round the World in the Endeavour in 1768 /69 /70 & /71 ~’

In 1919, the first students of Japanese were enrolled. By the early 1920s Inagaki headed the Department, until World War Two, when he was sent to an internment camp in Tatura, Victoria. UMA holds key documents of the founding of the Japanese teaching in the Office of the Registrar 1871-1966 series, as well as correspondence from Mr Inagaki’s wife Rose and, other prominent University figures seeking to secure his release from internment at Tatura.

The University of Melbourne Office of the Registrar Collection is a deep research resource, useful for a diverse range of research topics relating to the University in general as well as, academics, external individuals, and records relating to Faculties and buildings.

Read the rest of Inagaki’s story and the history of Japanese studies to current day on the Arts Faculty website.