Zodiac Man: a time capsule of weather prophecies, health predictions and popular culture in a 1616 almanac

If the mobile phone has become the essential life accessory of the 21st century, the almanac can be considered the indispensable accoutrement of the early modern period, reaching an apex of popular appeal in a ‘golden age’ of the 1640s. These annual calendars, which were published prolifically from late medieval times to the 18th century, provided cosmic guidance on the events of the year ahead – how to act, make decisions, cure diseases, solve misfortunes – according to the most propitious alignments of the heavens.

The moon’s aspect in relation to the major planets, for instance, would influence which days were best for hiring servants, beginning journeys and seeking the love of women, whilst others were fortuitous for repairing houses, putting on new clothes and conversing with old men. In an age where death and disaster were an everyday feature of life, to be without an almanac to supply forward navigation through the year could put you at risk of unseen misfortunes and potential catastrophes. What better to have forewarning at the year’s outset, so that you could prepare for and steer a course around impending calamities.

A fiercely competitive publishing market developed for both general and specialist almanacs, the former printed for an avid reading public and the latter for targeted audiences such as farmers, sailors, clergymen and for particular regional areas. Mainly produced as small pocket-sized booklets which could be carried and stored for ready consultation whether at home or on the road, almanacs were also issued as wall charts in sheet form. To minimise production costs and maximise profits, predictions and remedies contained in almanacs were necessarily short and to the point, and information was presented without detailed explanation.

A fiercely competitive publishing market developed for both general and specialist almanacs, the former printed for an avid reading public and the latter for targeted audiences such as farmers, sailors, clergymen and for particular regional areas. Mainly produced as small pocket-sized booklets which could be carried and stored for ready consultation whether at home or on the road, almanacs were also issued as wall charts in sheet form. To minimise production costs and maximise profits, predictions and remedies contained in almanacs were necessarily short and to the point, and information was presented without detailed explanation.

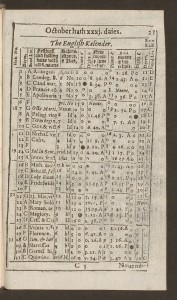

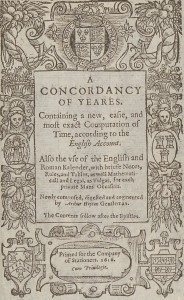

An early almanac in the Rare Books Collection, A concordancy for the yeares (1616) explaining ‘the infortunate and fatall dayes of the yeare, as also of the good and happy dayes’ was written by a respected Hertfordshire astrologer Arthur Hopcroft (1588?-1614).[i] Part astronomy, part astrology, the predictions contained in almanacs reflected a world view in which cosmology and the physical universe were harmoniously intertwined and with divinity and the workings of God.

Close reading of this pocket-sized handbook provides a fascinating encounter with a mini 400 year old time capsule, evoking the thoughts and preoccupations of the period in which it was produced. Hopcroft’s astrological calendar for October 1616 portends that the 5th will prove unhappy but the 3rd, 16th, 24th would be ‘not to bad’. By far the most perilous month of the year would be January with eight unfortunate days and no happy ones. Actions to be avoided on unhappy days included the beginning of ‘wordly affairs, giving birth, or being bled’.

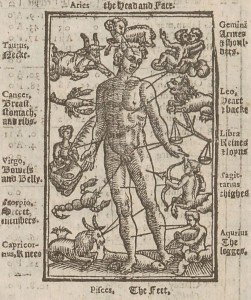

Zodiac Man

An essential element in popular almanacs was the Zodiac Man, who was pictured prominently with the 12 astrological signs around him, each governing a different body region. Inhabitants of the early modern world had a heightened awareness of the relationship between celestial bodies and the human form. Ill-favoured planetary alignments would result in illnesses in certain regions of the anatomy, as well as provoking calamitous events such as plagues and other natural disasters.

The relative positions of the celestial bodies when a patient first became ill were very important in diagnosis and treatment – often given more weight than actual symptoms – and the Zodiac Man helped explain and reinforce the most propitious remedies. A poem from a contemporary almanac explains the powers of each sign:

[Aries] The Ramme doth rule the head and face:

[Taurus] The Necke and Throat is Taurus’s place.

[Gemini] The Twinnes the Armes and Shoulders guide:

[Cancer] The Crab the Breast, the Spleene and side.

[Aquarius] The legges T’Aquarius doth fall:

[Pisces] And Feete to Pisces last of all.

[Leo] The Heart and Back’s hold Leo’s share:

[Virgo] Of Belly and Bowels the maid takes care.

[Libra] To Libra Reines and Loynes belong:

[Scorpio] The Secrets to the Scorpion.

[Sagittarius] The thighs the Archer doth direct:

[Capricorn] And Capricorne the knees protect.[ii]

The region of the knees were at most risk in January when Capricorn was dominant in the skies, whilst persons born under the sign of Aries were more prone to diseases of the head and face ‘such as head-aches, tooth-aches, migraines, pimples and small pox’.[iii]

Gradually as new scientific knowledge increased and faith in old beliefs lost their sway over the shared imagination, parodies of some of the more outlandish forecasts of almanacs began to appear. The Owles Almanack of 1618 predicted drolly that ‘the best time to fell timber was when one needed a good fire, and to cut hair when it is too long’, listed amusing sinners days as well as saints days, and included witty chronologies ‘commemorating the farmer who tried to teach his cow rope-dancing, and the gentleman who bought a periwig for his magpie’.[iv] Later in the century after dining out on Friday 14th June 1667, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary ‘thence we read and laughed at Lilly’s prophecies this month, in his Almanack this year!’

Despite Hopcroft’s own respected astrological credentials, he himself was to meet an untimely demise in his 26th year in the London parish of St Dunstan’s. Although the circumstances of his death remain unrecorded, we can only hope that he was able to find amelioration and guidance from the predictions he made in his concordances.

Susan Thomas, Rare Books Curator

Bibliography and further reading:

Hopcroft, Arthur. A concordancy of yeares: containing a new, easie, and most exact computation of time, according to the English account. Also the vse of the English and Roman kalender, with briefe notes, rules, and tables, as well mathematicall and legal, as vulgar, for each priuate mans occasion. Newly composed, digested and augmented by Arthur Hopton, gentleman. [London] : Printed [by Nicholas Okes] for the Company of Stationers, 1616.

Bertelsen, Lance. ‘Popular entertainment and instruction, literary and dramatic : chapbooks, advice books, almanacs, ballads, farces, pantomimes, prints and shows’ in John Richetti (ed.) The Cambridge history of English literature, 1660-1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Capp, B. S. (Bernard S.) Astrology and the popular press: English almanacs, 1500-1800. London : Faber, 1979.

Curth, Louise Hill. English almanacs, astrology and popular medicine : 1550-1700. Manchester : Manchester University Press, 2007.

Endnotes

[i] Hopcroft, Arthur. A concordancy of yeares… [London] : Printed [by Nicholas Okes] for the Company of Stationers, 1616.

[ii] Curth, Louise Hill. English almanacs, astrology and popular medicine : 1550-1700. p.121

[iii] Op cit, p.123

[iv] Capp, B. S. Astrology and the popular press: English almanacs, 1500-1800, p. 251