Diving for Dr Fox

A curious shadow has stowed itself alongside the Baillieu Library Print Collection. As a silhouette ‘cut and paste’ portrait, it is set apart from the majority of the collection which is printed. Silhouette cutting began in the 18th century and it was adopted as an art form in the 19th century when it reached its height of popularity. While reason for the inclusion of the shadow portrait in the Print Collection is not immediately apparent, what the work of art does reveal, when turned over to the verso, is a marvelous story featuring English doctors, an artist to the French royal family, a shipwreck and fervent collectors.

Augustin Amant Constant Fidèle Edouart, Dr Fox of Brislington, (1825-45), black card, gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne.

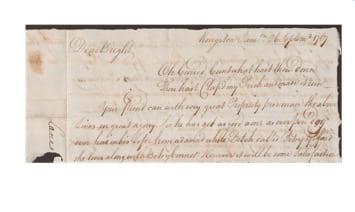

The inscription under the silhouette states: ‘Dr Fox of Brislington/ near Bristol.’ Here lies the identity of the shadowy gentleman; however, there is more than one doctor by the name of Fox associated with Brislington. The most likely candidate is the English psychiatrist Edward Long Fox (1761– 1835) who established an ‘insane asylum’ at Brislington House, near Bristol. Or possibly it could be his grandson, the physician also named Edward Long Fox (1832-1902) whose dates also span those of the artist.

The stamp on the verso reveals both the artist and a former owner: August Edouart, Silhouettist to the French Royal Family, 1826–1849, owned by Mrs E. Neville Jackson. Edouart travelled through Britain and also America, capturing the likenesses of as many as 50,000 people in silhouette. In 1831 he made portraits of the French Royal Family; Charles X of France was then visiting Holyrood House in England. His sitters were not always so well-known; nevertheless they are important identities from the 19th century.

Edouart wrote A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses a record of his experiences which is replete with examples of his works of art. His method was to cut the sitter’s likeness from black card with scissors which was pasted onto a light coloured sheet. Later in the century he found himself competing with early forms of photography and so added embellishments to his work. Sometimes his portraits were placed on a lithograph, a background scene executed by another artist, or they were highlighted with white chalk.

Dr Fox’s only accessories are a dignified top hat and umbrella. Both his austerity and the inscription of his name on the verso of the black card may suggest that he is one of Edouart’s duplicates: Edouart keep a duplicate copy of every portrait he made. He carefully preserved them in reference folios and transcribed the details of the sitter, writing their name on the back and under each silhouette. As he described in his treatise, these books of duplicate copies had a patented lock to prevent the unauthorised gaining access: ‘Many disappointments I have given those gentlemen, whom presume they are entitled to possess the Likeness of any of the ladies they like.’ (p. 24)

In 1849 his career as a silhouettist came to a devastating end with a shipwreck. He boarded the Oneida and was travelling from America to Europe when the ship was caught in a storm and wrecked on the coast of Guernsey. He was pulled from the sea by a Guernsey man, but his collection of reference folios was claimed by the ocean. Those dredged-up remnants representing his career he gave to the family who had rescued him, and he never cut another portrait. [1].

Yet the shipwreck did not bring an end to the regard for his silhouettes. Collector, writer and silhouette enthusiast Emily Neville Jackson took up his cause in the early 20th century. In 1911 she placed an advertisement in the Connoisseur Magazine asking for silhouettes to examine as part of her research on the history of the art form. The response by a member of the Guernsey family was how she came to purchase 16 of Edouart’s folios recovered from the shipwreck. [2]

A small label on the verso of the portrait of Dr Fox shows that Dr J. Orde Poynton, donor to the Baillieu Library and himself a medical practitioner, purchased the work from a Red Cross Antique and Art Exhibition in 1955.

While there is more to examine in this work on paper, this intriguing shadow in the Print Collection shows that it is always inspiring to dive into the university’s collections, and as with the case of Dr Fox, to emerge with a treasure to bring to the surface.

Kerrianne Stone (Curator, Prints)

[1] Helen and Nel Laughton, ‘August Edouart: A Quaker Album of American and English Duplicate Silhouettes 1827-1845’ in Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography. Jul 1985, Vol. 109 Issue 3, p. 388

[2] Helen and Nel Laughton, p.396

![Lavāʼiḥ [manuscript] [by] Nūr-al-Dīn ʻAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī](https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/librarycollections/files/2016/06/MUL-77-page-22-11mg1j7-300x231.png)