The story of how ‘Corroboree’ by Indigenous artist Tommy McRae came to the University of Melbourne Archives

The story of how Tommy McRae’s Corroboree came to the university is told from documentation at University of Melbourne Archives (UMA), telling one side of a complex history. UMA looks forward to meeting with McCrae’s descendants later in the year to show them more of his artwork and to learn more of the human story behind the documents.

Please note that images and names of deceased Indigenous people are contained within this article.

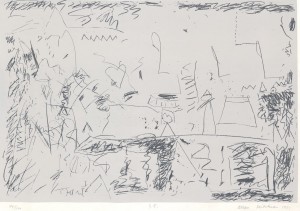

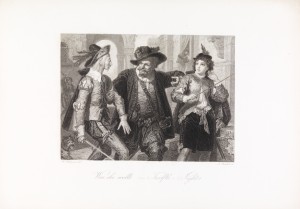

The scene from Corroboree or William Buckley and Dancers from the Wathaurong People, (c. 1890) by Indigenous artist Tommy McRae is pressed into the exterior of the University of Melbourne’s new Arts West building. This striking design, created in a joint venture by Architectus & ARM Architecture, transforms an archival object into a monumental work of public art and inscribes a powerful indigenous perspective on Australian history into the building’s skin.

McRae’s ink drawing is featured on the façade along with other objects from the university’s 23 cultural collections, selected specifically by the architects to capture the cultural span of the University and the history of the Arts Faculty. Who was McRae and how did the university become the custodian of his beautiful artwork?

The modest 20.5 x 25.5cm ink drawing on paper is part of the Foord Family Collection at the University of Melbourne Archives and it sits in box alongside business records and family correspondence. The inclusion of Corroboree in the Foord papers demonstrates the close personal relationships that McRae formed to maintain his independence at a time of dispossession, segregation and suffering.

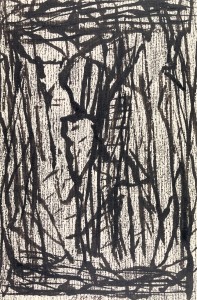

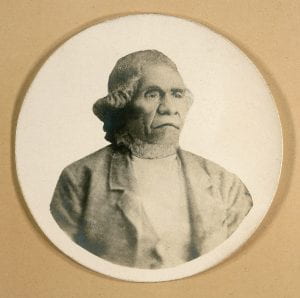

This portrait photograph was affixed to McRae’s ink drawing ‘Squatters of the Old Times”.

Tommy McRae

Tommy McRae, also known as Tommy Barnes and by his Aboriginal names Yackaduna or Warra-euea, was born in the 1830s in the Murray Valley area, near Corowa, most likely belonging to the Kwatkwat people. He died in 1901.

As a child, McRae lived through cataclysmic change. He witnessed confrontations between his relatives, the traditional owners of the land, and settlers. By 1845, pastoralists had occupied Kwatkwat territory and introduced large herds of livestock. Gold miners dug up land around Ovens, destroying indigenous plants.

In 1920, settler historian Arthur Andrews said that no more than 200 Aboriginal people remained in the Murray Valley. McRae became a leader of the indigenous people who remained. He stayed on his country and he watched how settlers, miners and his relatives related to each other. Then he made records of what he saw – his drawings.

As with other Aboriginal artists of the nineteenth century, McRae drew images of indigenous customs, including hunting animals, fighting, and ceremonial events like corroborees. These depictions were vital; missions such as Coranderrk prohibited indigenous people from living according to their customs and so their portrayals in artwork was a way of remembering and keeping culture alive. McRae’s images put indigenous people in the centre of the picture as the observers rather than the observed. Before he developing his artistic talents, McRae worked as a stockman for local pastoralists in the Murray Valley. One of his employers was John Foord, a prominent businessman in the

Wahgunyah region.

McRae’s Foord Family connection

Born in Brighton, England in 1819, John Foord immigrated to Australia in the 1830s. First he went to Parramatta and then in 1839 he occupied land on the Victorian side of the Murray River. In 1856 Foord set up the township of Wahgunyah; North Wahgunyah (later Corowa) across the river was established by 1861. Foord built the flower mill and the school and set up a paddle-steamer service.

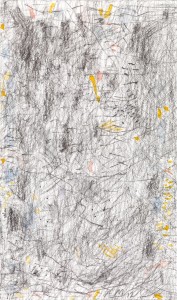

Research by UMA archivists suggests that the inclusion of two ink drawings by McRae in the Foord Family Collection, Corroboree and Squatters of the Old Times, is evidence of close ties between the artist and the Foord family. In 1864 Roderick Kilborn, a Canadian post master and Justice of the Peace living in Wahgunyah married John Foord’s daughter Sarah. Tommy McRae and his second wife Lily had three children together, sharing names with Sarah and Roderick’s children, Alexander, Henry and George. The McRae family also included other children from previous marriages and they along with Tommy’s brother’s family, lived mostly at Lake Moodemere during his most productive years as an artist.

Sarah Foord was John Foord’s daughter. She married Roderick Kilborn and had 8 children. Taken the day she

opened the bridge over the Murray.

It is unclear exactly when McRae began to develop his skills as an artist, it appears he was encouraged by Roderick Kilborn who likely witnessed McRae practicing traditional sand drawings to relate stories and history to his people. McRae and Kilborn appear to have had a close relationship. In the 1870s, Kilborn gave McRae a notebook, pen and ink. McRae filled the notebook and Kilborn was soon acting as de facto art agent, sending drawings to Lord Hopetoun, then Governor of Victoria, and other European settlers and dignitaries.

McRae’s status as an artist increased and soon he was filling notebooks for European customers. He was paid to create records of his view of colonisation and his stories of dispossession and ongoing cultural vitality. Kilborn also purchased notebooks full of McRae’s drawings. Kilborn’s grandson indicated to Muriel McGivern, author of a history of the Wahgunyah region, that Kilborn gave many of these sketches away, until only two ink drawings remained in the family.

Acquiring the Foord Family Papers

In the 1960s University Archivist Frank Strachan was interested in the Foord collection because of its expression of township, business and pastoralist endeavours as the study of business and economic history by students and researchers was the trend in the 1960s. The Foord Family collection is relatively small. It contains 8 boxes of business records from the flour mill and river boat businesses and papers relating to local agricultural associations that John Foord was involved in. It seems significant then that McRae’s ink drawings are two of the few non-business items in the collection.

New stories in the Archives

In 2016 the collection offers new directions and focus. As more material relating to indigenous heritage is identified at UMA, it’s clear that these objects are not preserved as evidence solely of the past but also as living cultural memories with value in the present. Corroboree is a record of indigenous perspectives and also of friendship that could cross the cultural divide.

The presence of McRae’s artwork on campus is a reminder that the place of Aboriginal people as valued leaders is often not told but it is a vital story that needs to be heard. Much correspondence held in UMA illustrates the culture shock of European migrants to the landscape of the new colony; however, there is little first person perspective which tells of the Indigenous experience of similar shock.

This artwork connects many lives, past and present and by tracing objects through provenance new perspectives can be found and complex narratives reinterpreted.

Bibliography

Andrews, Arthur, ‘The first settlement of the upper Murray 1835 to 1845 with a short account of over two hundred runs, 1835 to 1880.’ Sydney, 1920

Cooper, Carol and Urry, James, “Art, Aborigines and Chinese: a nineteenth century drawing by KwatKwat artist Tommy McRae. Aboriginal History vol 5, pt 1. 1981: 84

Cox, E.H. ‘An Aboriginal artist: inherited genius at Lake Tyers’, Argus, 8 June; Camera Supplement, 4

State Library of Victoria, ‘Artist William Barak’, Ergo, accessed 4 August 2016, http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/fight-rights/indigenous-rights/artist-william-barak

Sayers, Andrew, ‘McRae, Tommy (1835–1901)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mcrae-tommy-13074/text23649, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed online 15 August 2016.

Jane Beattie

Assistant Archivist – University of Melbourne Archives